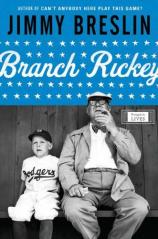

Branch Rickey

Review

Branch Rickey

On April 15, 1947, a 28-year-old black man by the name of Jack Roosevelt Robinson ran onto a baseball diamond in Brooklyn and right into the pages of American history. That simple American rite of spring changed this country forever.

The story of Jackie Robinson is well known. After a half-century of doing what they do best --- stick their collective heads in the sand --- professional baseball and its franchise owners finally recognized Robinson's importance by forever retiring his number 42 from the sport, an honor that even Babe Ruth and Hank Aaron never received. But what is less well known is that Robinson would never had been wearing Dodger blue that spring day if not for a man named Branch Rickey. Legendary reporter Jimmy Breslin, one of the greatest American writers of the 20th century, has written a slim biography of the man who made it happen.

Rickey's story is as fascinating as Robinson's. Breslin tell us that "Rickey carries with him a Midwestern religious fervor as strong as a wheat crop, and a political faith in anything Republican." He traced his roots back to one of eight families who sailed to the New World in 1646 and the man who founded the Methodist Church of America. As a young man growing up on a farm, he had a passion and knack for baseball. But his earliest attempt to play professional ball for the Cincinnati Reds were thwarted by a promise he made to his mother that he would not participate in the sport on Sundays.

But even with his devout ways, Rickey had a practical business streak that played a big role in Robinson's saga. Rickey's revolutionary activity was not limited to serving God. He was also interested in winning ball games and making a few bucks in the process. After his career as a player, he entered into baseball management, earning a law degree despite never having graduated high school. His place in baseball history was made well before Robinson arrived when, as an executive of the St. Louis Cardinals, he invented the farm system of baseball, signing up promising young athletes and then selling off the contracts of those he didn't need to other clubs and getting a 10% fee in the process.

Baseball, which Breslin describes at the time as "a sport for hillbillies with great eyesight," had never seen an innovative leader like Rickey. Players often had to deal not only with his legal mind and business sense but also his strict morality. The great Cardinal pitcher Dizzy Dean once found himself in need of $150 and went to Rickey. Breslin writes, "‘He didn't give me any money,' Dean reported of the conversation that followed. ‘All I got was a lecture on sex.'"

The Cardinals won six pennants and four World Series before Rickey left the organization, as he often did during his life in baseball, in a dispute over money. He landed a job in 1942 as general manager of the Brooklyn Dodgers, sort of a baseball Siberia in the 1920s and 1930s. Breslin tell us that Rickey "loved to plan." He saw an opportunity now with the Dodgers to put his "hands into the troubled history of America and fix it, starting in a baseball dugout." He writes, "But here on a street corner stands Branch Rickey, a lone white man with a fierce belief that it is the deepest sin against God to hold color against a person. On this day he means to change baseball and America, too. The National pastime, the game that teaches sportsmanship to children, must shake with shame, Rickey thought."

The year was 1943, and Rickey had a six-point plan to integrate baseball. And here is what is amazing. Rickey started implementing his plan, Breslin tells us, "four years before the armed forces were desegregated by Harry Truman, years before Brown vs. Board, decades before the Civil Rights Act and the great American law, Lyndon Baines Johnson's Voting Right Act of 1965 (and that is exactly how it should be printed in the books.). On this day, Martin Luther King, Jr., was a junior in an Atlanta high school."

And on that day, Rickey had not heard of Jackie Robinson yet. But he was a businessman, and as such he convinced other businessmen that black players would mean greater profits and more people at the gate to see this great social experiment. Plus, he no longer had the Cardinals' farm system; he could now use the excellent players from the Negro Leagues to make the Dodgers into a championship team, which he did. And black National League players --- veterans of the Negro Leagues --- dominated the sport for the next quarter-century.

Breslin recounts how painstakingly Rickey went about executing his plan. He knew that the first player must not only be a good ballplayer to counter the racist belief that black athletes were not as good as whites, but he must have the character to be able to suffer incredible racist abuse and not fight back. If he fought back, again it would prove the racist point that blacks and whites could never peacefully coexist. Rickey tells Robinson during their first meeting, "I'm looking for a ballplayer with the guts not to fight back."

Almost nine years before Dr. King launched his first nonviolent resistance campaign in Montgomery, Alabama, Robinson was practicing nonviolent resistance on the fields of America's segregated dreams, enduring racial slugs, raised spikes coming at him from sliding base runners, and fastballs aimed at his head --- Rickey also invented another staple of the modern game, the batting helmet --- and Robinson did it alone at first. He fought back the way Rickey taught him: "You've got to win this thing with hitting and throwing and fielding ground balls. Nothing else!"

Robinson would hit his way into the Baseball Hall of Fame with a .311 batting average for the Dodgers and become Rookie of the Year in 1947, the National League Most Valuable player in 1949 and a six-time All Star.

Jimmy Breslin is a national treasure, and BRANCH RICKEY shows that he is still at the top of his game. There is simply no American writer or reporter as good as Breslin when it comes to colorful descriptive writing. He takes a story and brings it to life as only a great reporter can. Banker George V. McLaughlin, for instance, "was called ‘George the Fifth' because he was in charge wherever he went and if he took a drink of Scotch that was none of your business." Or this: "Durocher had a temper that made the slightest confrontation suggest Verdun."

Sometimes revolutions happen where and when you least expect them from revolutionaries you would never imagine. Breslin gives Branch Rickey his proper place in one of our greatest revolutionary moments. If you love baseball, you will love this book. Even if you don't, it is a story well worth reading. Let's hope that Breslin keeps writing books for many more years to come.

Reviewed by Tom Callahan on April 25, 2011

Branch Rickey

- Publication Date: March 17, 2011

- Genres: Biography, Nonfiction

- Hardcover: 160 pages

- Publisher: Viking Adult

- ISBN-10: 0670022497

- ISBN-13: 9780670022496