Excerpt

Excerpt

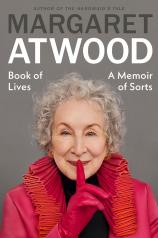

Book of Lives: A Memoir of Sorts

CHAPTER 1

FAREWELL TO NOVA SCOTIA

A THING MY MOTHER SAID:

MY MOTHER: Because our father’s name was Dr. Killam, kids at school used to tease us. They’d say, “Killam, Skin’em, and Eat’em.”

ME: Did they hurt your feelings?

MY MOTHER: Pooh. I wouldn’t give them the satisfaction.

A THING MY FATHER SAID:

“How long would it take two fruit flies, reproducing unchecked, to cover the entire Earth to a depth of two miles?”

(I don’t remember the answer to this, but it was a remarkably short time.)

Both my parents were from Nova Scotia. My father was born in 1906, my mother in 1909. Counting forward, you can see they would have been entering the job market just as the Great Depression of the 1930s was at its height. Coupled with that was the general decline of the Canadian Maritimes: Halifax had been a prosperous seaport in the nineteenth century, but then came the building of the railroads and the shift of the financial gravitational centre, first to Montreal, then Toronto. The city had a brief uptick during the First World War; later, after my parents had left Nova Scotia, it was the staging area for the Atlantic convoys due to its sheltered harbour. Some in Nova Scotia benefited from American Prohibition in the 1920s and early 1930s. A brisk smuggling business had fishing boats picking up booze from Saint-Pierre and Miquelon—French territory—and running it into the deep coves and estuaries of Maine. If Uncle Bill suddenly got a new roof on his barn, you didn’t ask him how he’d paid for it. But to profit from that trade you had to have a boat. Those who didn’t have boats were out of luck.

A joke from that time: “What’s the chief export of Nova Scotia?” “Brains.”

During those years, many Nova Scotians moved west in search of jobs. My parents were part of that exodus.

All the Nova Scotians I’ve known have been universally homesick. I’m not sure why, but so it has been. Both of my parents always referred to Nova Scotia as “home,” causing some confusion for me as a child: If Nova Scotia was “home,” where was I living? In some sort of not-home?

Ours is a family shrub, not a family tree. If you have roots in the Maritimes and meet someone else with similar roots, you find yourself picking your way through the shrubbery. Who was your father, who was your mother, grandfather, grandmother, from where, and so on, until you establish the fact that you are related. Or not. This can go on for some time.

So here’s the deep dive.

Nova Scotia, far from being uniformly Scottish in origin as the name might imply, was remarkably diverse. The Mi’kmaq lived there and still do, and are related to other Indigenous groups in New Brunswick and Maine. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, Nova Scotia was one of the first parts of what is now Canada to receive an influx of Europeans. French explorers; and French settlers and farmers who called themselves Acadian in honour of the comparatively idyllic place they found themselves in; then New Englanders who’d been enticed by cheap land. Later came a number of people who had been on the losing side of the American Revolution. These included the Free Blacks, who’d fought on the side of the British. Collectively, these immigrants from the States were known as United Empire Loyalists. Some of these were entangled in our family shrubbery.

Just before the Loyalists came German and French Protestants who’d been welcomed by the British during the French and Indian War with New France. Catholic New France—including Vermont and New Brunswick and what is now Quebec—was raiding the Protestant New England colonies with the help of its Indigenous allies, and vice versa. New England had the help of the British Army, while the French colonies were not so well supplied. Finally, in 1759, General Wolfe took Quebec City and New France fell to Britain. The New England colonists had no more need of the British Army, and did not see why they should be so heavily taxed. Result: The American Revolution, no taxation without representation, over-investment on the American side by the French monarchy, French debt, then the French Revolution.

While the wars were going on, the British had wanted to stuff as many Protestants as possible into Nova Scotia. One of these French Protestants joined our ancestral line. So did some Scots from the Highland Clearances in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, a period during which many small tenant farmers got turfed out of their age-old communities by their own clan chiefs. This was not only fallout from the defeat of the Scots in the 1746 Jacobite rising but was also a result of the spread of profitable sheep farming. I used to joke that I was descended from a long line of folks—going back to the Puritans, but not limited to them—who’d been kicked out of other countries for being contentious, or heretical, or indigent, or otherwise disagreeable.

Here are some of the names from the family shrubbery: Atwoods, Killams, Websters, McGowans, Lewises (from Wales), Nickersons, Moreaus, Robinsons, Chases. Those are just a few of the branches. If you go into the shrubbery, don’t get lost. It’s tangled.

The first of my father’s family to reach Nova Scotia’s South Shore came from Cape Cod. Cape Cod is still crawling with Atwoods, descended from those who arrived in the early seventeenth century, either on the Mayflower or shortly after it. They clustered around Wellfleet, Massachusetts, and then Chatham. Several museums, including the Atwood Museum in Chatham, are well worth a visit—don’t miss the cat door under the stairs through which a cat was stuffed every night to catch mice under the floor. (What did the house smell like? I wonder.) There’s also a portrait of a later dentist Atwood, who got himself painted in formal dress with three sets of dentures set out in front of him of which he was evidently proud.

It was the younger brother of the museum’s original Atwood owner who went to Nova Scotia in 1758, landing in Shelburne, a small port on the south coast. From Shelburne, the Atwoods spread out, giving rise to several privateers operating out of Liverpool, to a number of sailors, and to some loggers and farmers.

By the time my father was born, his family was living at Upper Clyde, quite a distance from the coast up the Clyde River. My grandfather ran a little sawmill that made white pine shingles, cedar being almost non-existent in Nova Scotia. Stacking these shingles at age six was the first of many jobs my father would hold. He enjoyed this immensely, according to him—children then being expected to contribute to the collective family economy as soon as they could.

The family would not have described itself as poor—they had a house, they had a cow, they had a parlour organ. My grandfather belonged to the Masons, which meant he must have been at least marginally respectable. But the family didn’t use money for as many things as people use it for today. If what was needed was something you could make—from wood, such as tables and chairs, or cloth or yarn, such as dresses, quilts, or mittens—you made it yourself. People got married, almost without exception. There weren’t many jobs for spinsters, and everyone knew that a man would have a very hard time running a small farm single-handed: a wife was necessary.

My grandmother, who was my grandfather’s second wife, kept chickens and ran a vegetable garden. She had the Rolls-Royce of wood-burning kitchen ranges, with an oven, a warming oven, a hot-water heater, and chrome trim. She smoked her own fish, and made butter in a churn; as a child I helped her make some.

Seeing this way of life, unchanged since the nineteenth century, was very helpful to me when I was writing Alias Grace. My grandmother’s stove was much fancier than anything available to Grace Marks, but the rhythm of the work and the shape of the days was much the same. My father, Carl, was the eldest of five, unless you count Uncle Freddy, son of the first wife. He was already grown up—a mysterious figure, lurking around the barn not saying much, and said to be not quite right in the head. The story we were told was that he’d been gassed in the First World War, but another informant said he’d already been like that. As with so many family stories, you don’t think to investigate them until there’s nobody left to ask.

Carl learned to read and write in a one-room schoolhouse. There was no nearby high school, so he took his high-school classes by correspondence course, encouraged by my grandmother, who’d been a schoolteacher. His studies would have been in addition to his farm chores and his work as a teenager in the winter logging camps, something my grandfather had also done. It was in the logging camps that he picked up an extensive vocabulary of swear words, said my mother. She heard him use them only once, when he hit his thumb with a sledgehammer while sinking the sand point for a hand pump. “The air turned blue,” she said with appreciation: here was a talent she hadn’t known he had.

Carl was very musical. I don’t know how he learned to play the fiddle, but he did. His younger brother, Uncle Elmer, played the banjo, and the two of them would provide the music for the local Saturday-night square dances, which could get rough—liquor consumed, fist fights outside. As the musicians, the two of them could avoid all that. Carl could sing at that time too: he was said to have had a beautiful baritone voice. But after he heard his first professional concerts as a young adult, once he was well and truly on his way to being a scientist, he never sang or played the fiddle again. My guess is that he tagged himself as an amateur. The furthest he would go was whistling: he was partial to Beethoven.

As a barefoot child walking from school, my father became fascinated by a giant green caterpillar he’d found, and it was this creature—the larval form of the cecropia moth—that drew his attention to the world of insects. He took the caterpillar home, made a little cage for it, fed it, and watched it transform, first into a pupa and then into a huge and colourful moth. This was the initial step in the process that led eventually to his career as an entomologist. Had he not followed this path he would never have met my mother and I would not have been born. So I owe my existence to a large green caterpillar.

One of Carl’s steps along the way was a stint at the normal school in Truro, where you were taught to be a schoolteacher. (I used to think it was where you learned to be normal, but this was not the case.) His intention was to teach school until he’d saved up enough money to get himself to university, but he was able to take a shortcut via summer jobs in entomology and a scholarship to Acadia University in Wolfville. From there he jumped via another scholarship to Macdonald College, the agricultural wing of Montreal’s McGill University, where he cleaned out rabbit hutches, lived in a tent and cooked for himself during the warmer months, and saved enough to send some money “home” so his three sisters could continue in school.

It was at the Truro normal school that my father first saw my mother, who was sliding down the main banister. He vowed then and there that she was the woman he would marry. It took him two tries—she turned him down the first time because she “was having too much fun”—but he managed it. He’d overcome so many barriers by then that he didn’t take an initial no as definitive.

“He surprised me. I thought he was just a friend,” said my mother of his first proposal. She had an abundance of swains and beaux swarming around, but my father was the only one who wasn’t pronounced “a jackass” by her father. He himself had pulled himself up by his bootstraps to become a doctor. Possibly he recognized in Carl—an extreme bootstrap-puller—something of himself.

Excerpted from BOOK OF LIVES by Margaret Atwood. Copyright © 2025 by Margaret Atwood. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Book of Lives: A Memoir of Sorts

- Genres: Memoir, Nonfiction

- hardcover: 624 pages

- Publisher: Doubleday

- ISBN-10: 038554751X

- ISBN-13: 9780385547512