Excerpt

Excerpt

Blue Shoes and Happiness: No. 1 Ladies Detective Agency

Aunty Emang, Solver of Problems

When you are just the right age, as Mma Ramotswe was, and when you

have seen a bit of life, as Mma Ramotswe certainly had, then there

are some things that you just know. And one of the things that was

well known to Mma Ramotswe, only begetter of the No. 1 Ladies'

Detective Agency (Botswana's only ladies' detective agency), was

that there were two sorts of problem in this life. Firstly, there

were those problems-and they were major ones-about which one could

do very little, other than to hope, of course. These were the

problems of the land, of fields that were too rocky, of soil that

blew away in the wind, or of places where crops would just not

thrive for some sickness that lurked in the very earth. But looming

greater than anything else there was the problem of drought. It was

a familiar feeling in Botswana, this waiting for rain, which often

simply did not come, or came too late to save the crops. And then

the land, scarred and exhausted, would dry and crack under the

relentless sun, and it would seem that nothing short of a miracle

would ever bring it to life. But that miracle would eventually

arrive, as it always had, and the landscape would turn from brown

to green within hours under the kiss of the rain. And there were

other colours that would follow the green; yellows, blues, reds

would appear in patches across the veld as if great cakes of dye

had been crumbled and scattered by an unseen hand. These were the

colours of the wild flowers that had been lurking there, throughout

the dry season, waiting for the first drops of moisture to awaken

them. So at least that sort of problem had its solution, although

one often had to wait long, dry months for that solution to

arrive.

The other sorts of problems were those which people made for

themselves. These were very common, and Mma Ramotswe had seen many

of them in the course of her work. Ever since she had set up this

agency, armed only with a copy of Clovis Andersen's The Principles

of Private Detection-and a great deal of common sense-scarcely a

day had gone by without her encountering some problem which people

had brought upon themselves. Unlike the first sort of

problem-drought and the like-these were difficulties that could

have been avoided. If people were only more careful, or behaved

themselves as they should, then they would not find themselves

faced with problems of this sort. But of course people never

behaved themselves as they should. "We are all human beings," Mma

Ramotswe had once observed to Mma Makutsi, "and human beings can't

really help themselves. Have you noticed that, Mma? We can't really

help ourselves from doing things that land us in all sorts of

trouble."

Mma Makutsi pondered this for a few moments. In general, she

thought that Mma Ramotswe was right about matters of this sort, but

she felt that this particular proposition needed a little bit more

thought. She knew that there were some people who were unable to

make of their lives what they wanted them to be, but then there

were many others who were quite capable of keeping themselves under

control. In her own case, she thought that she was able to resist

temptation quite effectively. She did not consider herself to be

particularly strong, but at the same time she did not seem to be

markedly weak. She did not drink, nor did she over-indulge in food,

or chocolate or anything of that sort. No, Mma Ramotswe's

observation was just a little bit too sweeping and she would have

to disagree. But then the thought struck her: Could she resist a

fine new pair of shoes, even if she knew that she had plenty of

shoes already (which was not the case)?

"I think you're right, Mma," she said. "Everybody has a weakness,

and most of us are not strong enough to resist it."

Mma Ramotswe looked at her assistant. She had an idea what Mma

Makutsi's weakness might be, and indeed there might even be more

than one.

"Take Mr J.L.B. Matekoni, for example," said Mma Ramotswe.

"All men are weak," said Mma Makutsi. "That is well known." She

paused. Now that Mma Ramotswe and Mr J.L.B. Matekoni were married,

it was possible that Mma Ramotswe had discovered new weaknesses in

him. The mechanic was a quiet man, but it was often the

mildest-looking people who did the most colourful things, in secret

of course. What could Mr J.L.B. Matekoni get up to? It would be

very interesting to hear.

"Cake," said Mma Ramotswe quickly. "That is Mr J.L.B. Matekoni's

great weakness. He cannot help himself when it comes to cake. He

can be manipulated very easily if he has a plate of cake in his

hand."

Mma Makutsi laughed. "Mma Potokwane knows that, doesn't she?" she

said. "I have seen her getting Mr J.L.B. Matekoni to do all sorts

of things for her just by offering him pieces of that fruit cake of

hers."

Mma Ramotswe rolled her eyes up towards the ceiling. Mma Potokwane,

the matron of the orphan farm, was her friend, and when all was

said and done she was a good woman, but she was quite ruthless when

it came to getting things for the children in her care. She it was

who had cajoled Mr J.L.B. Matekoni into fostering the two children

who now lived in their house; that had been a good thing, of

course, and the children were dearly loved, but Mr J.L.B. Matekoni

had not thought the thing through and had failed even to consult

Mma Ramotswe about the whole matter. And then there were the

numerous occasions on which she had prevailed upon him to spend

hours of his time fixing that unreliable old water pump at the

orphan farm-a pump which dated back to the days of the Protectorate

and which should have been retired and put into a museum long ago.

And Mma Potokwane achieved all of this because she had a profound

understanding of how men worked and what their weaknesses were;

that was the secret of so many successful women-they knew about the

weaknesses of men.

That conversation with Mma Makutsi had taken place some days

before. Now Mma Ramotswe was sitting on the verandah of her house

on Zebra Drive, late on a Saturday afternoon, reading the paper.

She was the only person in the house at the time, which was unusual

for a Saturday. The children were both out: Motholeli had gone to

spend the weekend with a friend whose family lived out at

Mogiditishane. This friend's mother had picked her up in her small

truck and had stored the wheelchair in the back with some large

balls of string that had aroused Mma Ramotswe's interest but which

she had not felt it her place to ask about. What could anybody want

with such a quantity of string? she wondered. Most people needed

very little string, if any, in their lives, but this woman, who was

a beautician, seemed to need a great deal. Did beauticians have a

special use for string that the rest of us knew nothing about? Mma

Ramotswe asked herself. People spoke about face-lifts; did string

come into face-lifts?

Puso, the boy, who had caused them such concern over his

unpredictable behaviour but who had recently become much more

settled, had gone off with Mr J.L.B. Matekoni to see an important

football match at the stadium. Mma Ramotswe did not consider it

important in the least-she had no interest in football, and she

could not see how it could possibly matter in the slightest who

succeeded in kicking the ball into the goal the most times-but Mr

J.L.B. Matekoni clearly thought differently. He was a close

follower and supporter of the Zebras, and tried to get to the

stadium whenever they were playing. Fortunately the Zebras were

doing well at the moment, and this, thought Mma Ramotswe, was a

good thing: it was quite possible, she felt, that Mr J.L.B.

Matekoni's depression, from which he had made a good recovery,

could recur if he, or the Zebras, were to suffer any serious

set-back.

So now she was alone in the house, and it seemed very quiet to her.

She had made a cup of bush tea and had drunk that thoughtfully,

gazing out over the rim of her cup onto the garden to the front of

the house. The sausage fruit tree, the moporoto, to which she had

never paid much attention, had taken it upon itself to produce

abundant fruit this year, and four heavy sausage-shaped pods had

appeared at the end of a branch, bending that limb of the tree

under their weight. She would have to do something about that, she

thought. People knew that it was dangerous to sit under such trees,

as the heavy fruit could crack open a skull if it chose to fall

when a person was below. That had happened to a friend of her

father's many years ago, and the blow that he had received had

cracked his skull and damaged his brain, making it difficult for

him to speak. She remembered him when she was a child, struggling

to make himself understood, and her father had explained that he

had sat under a sausage tree and had gone to sleep, and this was

the result.

She made a mental note to warn the children and to get Mr J.L.B.

Matekoni to knock the fruit down with a pole before anybody was

hurt. And then she turned back to her cup of tea and to her perusal

of the copy of The Daily News, which she had unfolded on her lap.

She had read the first four pages of the paper, and had gone

through the small advertisements with her usual care. There was

much to be learned from the small advertisements, with their offers

of irrigation pipes for farmers, used vans, jobs of various sorts,

plots of land with house construction permission, and bargain

furniture. Not only could one keep up to date with what things

cost, but there was also a great deal of social detail to be

garnered from this source. That day, for instance, there was a

statement by a Mr Herbert Motimedi that he would not be responsible

for any debts incurred by Mrs Boipelo Motimedi, which effectively

informed the public that Herbert and Boipelo were no longer on

close terms-which did not surprise Mma Ramotswe, as it happened,

because she had always felt that that particular marriage was not a

good idea, in view of the fact that Boipelo Motimedi had gone

through three husbands before she found Herbert, and two of these

previous husbands had been declared bankrupt. She smiled at that

and skimmed over the remaining advertisements before turning the

page and getting to the column that interested her more than

anything else in the newspaper.

Some months earlier, the newspaper had announced to its readers

that it would be starting a new feature. "If you have any

problems," the paper said, "then you should write to our new

exclusive columnist, Aunty Emang, who will give you advice on what

to do. Not only is Aunty Emang a BA from the University of

Botswana, but she also has the wisdom of one who has lived

fifty-eight years and knows all about life." This advance notice

brought in a flood of letters, and the paper had expanded the

amount of space available for Aunty Emang's sound advice. Soon she

had become so popular that she was viewed as something of a

national institution and was even named in Parliament when an

opposition member brought the house down with the suggestion that

the policy proposed by some hapless minister would never have been

approved of by Aunty Emang.

Mma Ramotswe had chuckled over that, as she now chuckled over the

plight of a young student who had written a passionate love letter

to a girl and had delivered it, by mistake, to her sister. "I am

not sure what to do," he had written to Aunty Emang. "I think that

the sister is very pleased with what I wrote to her as she is

smiling at me all the time. Her sister, the girl I really like,

does not know that I like her and maybe her own sister has told her

about the letter which she has received from me. So she thinks now

that I am in love with her sister, and does not know that I am in

love with her. How can I get out of this difficult situation?" And

Aunty Emang, with her typical robustness, had written: "Dear

Anxious in Molepolole: The simple answer to your question is that

you cannot get out of this. If you tell one of the girls that she

has received a letter intended for her sister, then she will become

very sad. Her sister (the one you really wanted to write to in the

first place) will then think that you have been unkind to her

sister and made her upset. She will not like you for this. The

answer is that you must give up seeing both of these girls and you

should spend your time working harder on your examinations. When

you have a good job and are earning some money, then you can find

another girl to fall in love with. But make sure that you address

any letter to that girl very carefully."

There were two other letters. One was from a boy of fourteen who

had been moved to write to Aunty Emang about being picked upon by

his teacher. "I am a hard-working boy," he wrote. "I do all my

schoolwork very carefully and neatly. I never shout in the class or

push people about (like most other boys). When my teacher talks, I

always pay attention and smile at him. I do not trouble the girls

(like most other boys). I am a very good boy in every sense. Yet my

teacher always blames me for anything that goes wrong and gives me

low marks in my work. I am very unhappy. The more I try to please

this teacher, the more he dislikes me. What am I doing

wrong?"

Everything, thought Mma Ramotswe. That's what you are doing wrong:

everything. But how could one explain to a fourteen-year-old boy

that one should not try too hard; which was what he was doing and

which irritated his teacher. It was better, she thought, to be a

little bit bad in this life, and not too perfect. If you were too

perfect, then you invited exactly this sort of reaction, even if

teachers should be above that sort of thing. But what, she

wondered, would Aunty Emang say?

"Dear Boy," wrote Aunty Emang. "Teachers do not like boys like

you..."

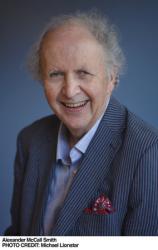

Excerpted from BLUE SHOES AND HAPPINESS: No. 1 Ladies Detective

Agency © Copyright 2011 by Alexander McCall Smith. Reprinted

with permission by Anchor, , a division of Random House, Inc. All

rights reserved.