Excerpt

Excerpt

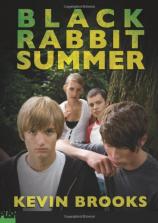

Black Rabbit Summer

There were plenty of things I could have been doing that night. It was still only half past nine. I could have been watching TV, or a DVD, or getting ready to go out somewhere. I could have been watching TV or a DVD and then getting ready to go out somewhere.

But I knew I wasn’t going to.

I was happy enough doing nothing.

Happy enough?

I don’t know.

I suppose I was happy enough.

So, anyway, that’s what I was doing when the telephone rang and the summer of this story began — I was lying on my bed, staring at the ceiling, minding my own mindless business. The sound of the phone ringing didn’t really mean anything to me. It was just a noise, the familiar dull trill of the phone in the hallway downstairs, and I knew it wasn’t going to be for me. It was probably just Dad, ringing from work, or one of Mum’s friends, calling for a chat…

It wasn’t anything to get excited about.

It wasn’t anything to get anything about.

It was just something to listen to.

I could hear Mum downstairs now — coming out of the living room, walking down the hall, quietly clearing her throat, picking up the phone…

“Hello?” I heard her say.

A short pause.

Then, “Oh, hello, Nicole. How are you?”

Nicole? I thought, my heart quickening slightly. Nicole?

“Pete!” Mum called out. “Phone!”

I didn’t move for a moment. I just lay there on the bed, staring at the bedroom door, trying to work out why Nicole Leigh would be phoning me at half past nine on a Thursday night. Why would she be phoning me at all? She hadn’t phoned me in ages.

“Pete!” Mum called out again, louder this time. “Telephone!”

I didn’t really feel like talking to anyone just then, and I half-thought about asking Mum to tell Nicole that I was out, that I’d call her back later, but then I realized that in order to do that I’d have to get up and go downstairs anyway, and then Mum would want to know why I didn’t want to talk to Nicole, and I’d have to think of something to tell her…

And I couldn’t be bothered with all that.

And even if I could…

Well, it wasn’t just anyone on the phone, was it?

It was Nicole Leigh.

I got up off the bed, stretched the stiffness from my neck, and made my way downstairs.

When I got there, Mum was standing at the end of the hallway with her hand cupped over the phone.

“It’s Nicole,” she said in an exaggerated whisper, mouthing the words as if it was some kind of secret.

“Thanks,” I told her, taking the phone from her hand. I waited until she’d gone back into the living room, then I put the phone to my ear. “Hello?”

“Good evening,” a fake-posh voice said. “Is this Mr. Peter Boland?”

“Hey, Nic.”

“Shit,” she laughed. “How’d you know it was me?”

“I’m telepathic,” I said. “I was just thinking about you when the phone rang—”

“Liar. Your mum told you it was me, didn’t she?”

“Yeah.”

Nic laughed again. It was a nice laugh, kind of husky and sweet, and it brought back memories of other times… times I thought I’d forgotten.

“I’m not interrupting anything, am I?” she said.

“What do you mean?”

“Nothing… it’s just that you took a long time getting to the phone, that’s all. And I heard your mum covering the phone and whispering.”

“She always does that,” I said. “It doesn’t mean anything. I was just upstairs in my room…”

“On your own?”

I could hear the smile in her voice.

“Yeah,” I said. “On my own.”

“Right.”

I stared at the wall, listening to the muffled silence at the other end of the line, imagining the look on Nic’s face — amused, attentive, engagingly secretive.

“So, Pete,” she went on. “How’s it going?”

“All right, I suppose.”

“What’ve you been doing with yourself?”

“Not much. How about you?”

“Christ,” she sighed, “all I’ve been doing for the last three weeks is packing.”

“Packing?”

“Yeah, you know… for when we go to Paris.”

“I thought you weren’t going until the end of September?”

“We’re not, but Mum and Dad are away for the next few weeks and they’re trying to get most of the packing done before they go. There’s cardboard boxes and crap all over the place at the moment. It’s like living in a warehouse.”

“Sounds like fun.”

“Yeah…”

I kept quiet for a while, not saying anything, waiting to find out what she really wanted to talk about. Nicole has never been one for small talk, and I knew she wouldn’t have called me after all this time just to talk about cardboard boxes. So I just stared at the wall and waited.

Eventually she said, “Listen, Pete… are you still there?”

“Yeah.”

“What are you doing on Saturday?”

“Saturday? I don’t know… not much. Why?”

“You know that carnival up at the town park?”

“Yeah.”

“Well, it’s the last day on Saturday, and I thought we could all meet up and have a night out. Just the four of us — you, me, Eric, and Pauly. You know, for old times’ sake.”

“Old times?”

“Yeah, you know what I mean — the gang… the four of us. I mean, it wasn’t that long ago, was it? I just thought, you know…”

“What?”

“I just thought we should all meet up again before it’s too late.”

“Too late for what?”

“Well, you’re going off to college, me and Eric are going to Paris, Pauly’s probably getting a job… this might be the last chance we get to be together again.”

“Yeah, I suppose…”

“Come on, Pete… Eric and Pauly are up for it. We’re going to meet in the old hideout in Back Lane—”

“The hideout?”

She laughed. “Yeah, I know… I was just thinking about it a while ago, you know, remembering how we built it and everything, and I suddenly realized it’d be a really good place to meet up for the last time. It’ll be fun — just like the old hideout parties we used to have. Bring a few bottles, get a bit drunk… then afterward we can all go on to the carnival together and throw up on the roller coaster.” She laughed again. “You’ve got to come, Pete. It won’t be the same without you.”

“What about Raymond?”

Nicole hesitated. “Raymond Daggett?”

“Yeah. I mean, there weren’t just the four of us in the old gang, were there? Raymond was with us most of the time.”

“Well, yeah, I know. But Raymond… I mean, it’s not really his kind of thing, is it?”

“What do you mean?”

“You know… going out, going to the carnival, meeting up with Eric and Pauly. I just don’t think he’d enjoy it, that’s all.”

“Why not?”

“Look, Pete,” she sighed. “I’m not saying I don’t want him to come—”

“What are you saying then?”

“Nothing. It’s just…”

“What?”

“Nothing. It doesn’t matter.” She sighed again. “If you want Raymond to come—”

“I don’t even know if I’m coming yet.”

“Of course you are,” she said, suddenly brightening up. “You’re not going to say no to me, are you?”

“No.”

She laughed again, but this time it sounded a little bit forced, and I got the impression that she was making herself go along with the joke, when in fact she wanted to be serious… and I didn’t know how I felt about that. There was something almost intimate about the way she was talking to me, and if I hadn’t known better, I would have sworn she was flirting with me. But I did know better. Nicole Leigh wouldn’t flirt with me. We were past all that now. We hardly even knew each other anymore. We moved in different circles. We did different things. We had different friends. All we had in common now was the shared memory of a time when we used to hang out together with Raymond and Pauly and Eric. Memories of gangs and hideouts, of long days down by the river, or in the woods… memories of breathless young kisses and awkward fumbles in the abandoned factory at the end of the lane…

Memories… that’s all they were.

Kid’s stuff.

“Pete?” I heard Nic say. “Did you hear me?”

“What?”

“I said, don’t forget to bring a bottle.”

“Sorry?”

“A bottle… something to drink. On Saturday.”

“Oh, yeah… right.”

“We’re meeting in the hideout at nine-thirty, OK?”

“The hideout in Back Lane?”

“Yeah, the one up the bank near the old factory. Opposite the gas towers.”

“Right.”

She hesitated for a moment. “Are you still thinking of bringing Raymond?”

“I don’t see why not.”

“All right. But you can’t spend the whole night looking after him.”

“Raymond doesn’t need looking after.”

“I didn’t mean it like that. I just meant…” Her voice trailed off and I heard her lighting a cigarette. “Anyway, listen,” she went on.

“After the carnival we’re all going back to my place. Mum and Dad’ll be away by then, so… you know… if you want to stay over, you’re welcome.” She paused for a moment, then added quietly, “No strings attached.”

“Right…”

“OK. Well, I’ll see you on Saturday then.”

“Yeah.”

“Nine-thirty.”

“Nine-thirty.”

“All right, then. See you…”

“Yeah, bye.”

You know what it’s like when you’re talking to someone, and at the time you’re not quite sure what they’re trying to say, but then, when they’ve gone, and you’ve had time to think about it, you realize that in actual fact you haven’t got a clue what they were trying to say? Well, that’s how I felt after I’d said good-bye to Nicole. I just stood there in the hallway, staring dumbly at the floor, thinking to myself…

Old times?

Hideout parties?

Carnivals and roller coasters?

What the hell was that all about?

I didn’t get to sleep for a long time that night. As I lay in my bed, staring into the moonlit darkness, there were so many thoughts stuffing up my head that I could feel them seeping out of my skull. Sweaty thoughts, sticky and salty, oozing out of my ears, my eyes, my mouth, my skin.

Thoughts, images, memories.

The sound of Nic’s voice: If you want to stay over, you’re welcome… no strings attached.

The pictures in my mind: me and Nic at a party when we were thirteen, maybe fourteen years old, locked in a bathroom together… too young to know what we were doing, but still trying to do it anyway…

You’re not going to say no to me, are you?

I got out of bed then, covered in sweat, and went over to stand at the open window. The air was stuffy and thick, the night warm and still. I wasn’t wearing any pajamas or anything — it was too hot for that — and although there was no breeze coming in through the window, I could feel the sweat beginning to cool on my skin.

I shivered.

Hot and cold.

It was sometime in the early morning now. Two o’clock, three o’clock, something like that. The street down below was empty and quiet, but I could hear faint sounds drifting over from the main road nearby — the occasional passing car, late-night clubbers going home, a distant shout, drunken voices…

The sounds of the night.

I gazed down the street at Raymond Daggett’s house. It was dark, the curtains closed, the lights all out. In the pale glow of a streetlight, I could see the alleyway that lead around to the back of his house, and I could see all the crap that littered his front yard — bike frames, boxes, skids, trash bags. I stared at Raymond’s bedroom window, wondering if he was in there or not.

Raymond didn’t always spend the night in his room. Sometimes he’d wait until his parents were asleep, then he’d creep downstairs, go outside, and spend the night in the garden with his rabbit. He kept the rabbit in a hutch by a shed at the bottom of the backyard. If the night was cold, he’d take his rabbit into the shed with him and they’d snuggle up together in some old burlap sack or something. But on a warm night, like tonight, he’d let the rabbit out of its hutch and they’d both just sit there, quietly content, beneath the summer stars.

I wondered if they were out there now.

Raymond and his Black Rabbit.

It all started for Raymond when he was eleven years old and his parents gave him a rabbit for his birthday. It was a scrawny little thing, black all over, with slightly glazed eyes, a matted tail, and big patches of mangy fur down its back. I think Raymond’s dad bought it off someone in a pub or something. Or maybe he just found it… I don’t know. Anyway, wherever his dad got it from, Raymond was pretty surprised to get a rabbit for his birthday. Firstly, because he hadn’t asked for one, and this was the first time in his life he’d ever gotten anything from his parents without asking for it. Secondly, because his parents usually forgot his birthday. And thirdly, as Raymond admitted to me later, he didn’t even like rabbits at the time.

But he didn’t let his parents know that. They wouldn’t have been pleased. And Raymond had learned a long time ago that it wasn’t a good idea to displease his parents. So he’d thanked them very much, and he’d smiled awkwardly, and he’d held the rabbit in his arms and stroked it.

“What are you going to call him?” his mother had asked.

“Raymond,” said Raymond. “I’ll call him Raymond.”

But he was lying. He wasn’t going to call the rabbit Raymond. He wasn’t going to call it anything. Why should he? It was a rabbit. Rabbits don’t have names. They don’t need names. They’re just dumb little animals.

It was probably about a year or so later that Raymond first told me his rabbit had started talking to him. I thought at first he was just messing around, making up one of his odd little stories — Raymond was always making up odd little stories — but after a while I began to realize he was serious. We were down at the river at the time — just the two of us, hanging around on the bank, looking for voles, skipping stones across the river… the usual kind of stuff — and as Raymond started telling me about his rabbit, I could tell by the look in his eyes that he believed every word he was saying.

“I know it sounds really stupid,” he told me, “and I know he’s not really talking to me, but it’s like I can hear things in my head.”

“What kind of things?” I asked him.

“I don’t know… words, I suppose. But they’re not really words. They’re like… I don’t know… like floating whispers in the wind.”

“Yeah, but how do you know they’re coming from the rabbit?” I said.

“I mean, it could be just some kind of weird stuff going on in your head.”

“He tells me things.”

I stared at him. “What kind of things?”

Raymond shrugged and lobbed a pebble into the river. “Just things… he says hello sometimes. Thank you. Stuff like that.”

“Is that it? Just hello and thank you?”

Raymond gazed thoughtfully across the river, his eyes kind of glazed and distant. When he spoke, his voice sounded strange. “A fine sky this evening…”

“What?” I said.

“That’s what Black Rabbit said last night. He told me it was a fine sky this evening.”

“A fine sky this evening?”

“Yeah… and green is fresh like water. He said that, too. Green is fresh like water. And the other day he said This good wooden house and Straw smell blue sky. He says all kinds of things.”

Raymond went quiet then, and I couldn’t think of anything else to say, so we just sat there for a while, not doing anything, just staring in silence at the murky brown waters of the river.

After a minute or two, Raymond turned and looked at me. “I know it doesn’t make any sense, Pete, and I know it’s kind of weird… but I really like it. It’s like when I get home from school every day and I go down to the hutch at the bottom of the backyard and I feed Black Rabbit and give him fresh water and let him out for a run and clean his hutch… it’s like I’ve got this friend who tells me stuff that’s OK. He says stuff that doesn’t hurt me. It makes me feel good.”

Two years later, when Black Rabbit died of a fungal infection of the mouth, Raymond cried like he’d never cried before. He cried for three days solid. He was still crying when I helped him bury Black Rabbit’s body in an empty cornflakes box in his backyard.

“He told me not to cry,” Raymond sobbed, filling in the hole, “but I just can’t help it.”

“Who did?” I asked him, thinking he meant his dad. “Who told you not to cry?”

“Black Rabbit…” Raymond sniffed hard and wiped the snot from his nose. “I know what to do… I mean, I know he’s not gone.”

“What do you mean?”

“He told me to bring him home.”

I didn’t know what Raymond was talking about at the time, but when I went over to see him the next day and found out that he’d been down to the pet shop and bought himself another black rabbit… well, I still didn’t understand what he was talking about, but I kind of realized what he meant. Because, as far as Raymond was concerned, the rabbit he’d gotten from the pet shop wasn’t just another black rabbit, it was the same Black Rabbit. Same eyes, same ears, same jet-black fur… same whispered voice.

Raymond had done as he was told — he’d brought Black Rabbit home.

…

I shivered again. The sweat had dried on my skin now, and I was beginning to feel cool enough to get back into bed. I stayed at the window for a while longer, though, thinking about Raymond, wondering if he was out there… sitting in the darkness, listening to the whispers in his head.

A fine sky this evening.

This good wooden house.

Straw smell blue sky.

I thought about what Nicole had said — about Raymond not wanting to go to the carnival on Saturday — and I knew she was probably right. I was pretty sure that he’d want to go if it was just me and him, but I didn’t know how he’d feel about meeting up with the others. I didn’t know how I felt about it myself, either. Nicole and Eric? Pauly Gilpin? It just seemed so… I don’t know. Like stepping back into the past: back to grade school, sitting together at the back of the class; back to middle school, watching out for each other in the playground, hanging around after school, spending our weekends and school holidays together…

We were friends then.

We had connections: Nicole and Eric were twins, Nic and me pretended we loved each other, Pauly looked up to Eric, Eric looked after Nic…

Connections.

But that was then, and things were different then. We were different. We were kids. And we weren’t kids anymore. We’d moved on to junior high school, we’d turned thirteen, fourteen, fifteen, sixteen… and things had gradually changed. You know how it is — the world gets bigger, things drift apart, your childhood friends become people you used to know. I mean, you still know them, you still see them at school every day, you still say hello to them… but they’re not what they were anymore.

The world gets bigger.

Not everything changes, though.

Raymond and me had never changed. Our world had never gotten any bigger. We’d always been friends. We’d been friends before the others, we’d been friends with the others and apart from the others, and, in lots of ways, we’d been friends in spite of the others.

We were friends.

Then and now.

And so the idea of us all getting together again on Saturday… well, it just felt really strange. A bit scary, I suppose. A bit pointless, even. But at the same time it was sort of exciting, too. Exciting in a strangely-scary-and-pointless kind of way.

I’d turned away from the window now and was gazing over at a black porcelain rabbit that I keep on top of my chest of drawers. It was a sixteenth birthday present from Raymond. A black porcelain rabbit, almost life-size, sitting on all fours. It’s a beautiful thing — glossy and smooth, with shining black eyes, a necklace of flowers, and a face that seems to be frowning. It’s as if the rabbit is thinking about something that happened a long time ago, something saddening, something that will always prey on its mind.

I don’t usually get all emotional about stuff, but I was really quite touched when Raymond had given me the rabbit. Everyone else had given me the kind of presents you expect on your sixteenth birthday — Mum and Dad had given me money, a girl I’d gone out with a couple of times had given me a night to remember, and I’d gotten a few cards and jokey little things from friends at school — but this, Raymond’s rabbit… well, this was a proper present. A serious present, given with thought and feeling.

“You don’t have to keep it if you don’t want to,” Raymond had mumbled awkwardly as he’d watched me unwrap it. “I mean, I know it’s a bit… well, you know… I mean, if you don’t like it…”

“Thanks, Raymond,” I’d told him, holding the porcelain rabbit in my hands. “It’s wonderful. I love it. Thank you.”

He’d lowered his eyes and smiled then, and the way that’d made me feel was better than all the best Christmas and birthday presents rolled into one.

I looked at the rabbit now — its porcelain body shimmering in the moonlight, its black eyes shining and sad.

“What do you think, Raymond?” I said quietly. “Do you want to go to the carnival, take a trip down memory lane? Or should we both just stay where we are, hiding away in our own small worlds?”

I don’t know what I was expecting, but the porcelain rabbit didn’t say anything back to me. It just sat there, black-eyed and sad, gazing at nothing. And after a while I began to feel pretty stupid — standing by the window in the middle of the night, naked and alone, talking to a porcelain rabbit…

Mum was right — I definitely needed to get out a bit more.

I shook my head and got back into bed.

Excerpted from BLACK RABBIT SUMMER © Copyright 2011 by Kevin Brooks. Reprinted with permission by Push, an imprint of Scholastic, Inc. All rights reserved.

Black Rabbit Summer

- Genres: Mystery

- paperback: 512 pages

- Publisher: Push

- ISBN-10: 0545060893

- ISBN-13: 9780545060899