Excerpt

Excerpt

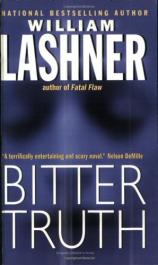

Bitter Truth

Chapter One

Ailurophobia

"I know of nothing more despicable and pathetic than a man who devotes all the hours of the waking day to the making of money for money's sake."

-- John D. Rockefeller

En Route to Belize City, Belize

I suppose every hundred million dollars has its own sordid story and the hundred million I am chasing is no exception.

I am on a TACA International flight to Belize in search of my fortune. Underneath the seat in front of me lies my briefcase and in my briefcase lies all I need, officially, to pick my fortune up and take it home with me. I lift the briefcase onto my lap and open it, carefully pulling out the file folder, and from that folder, with even more care, pulling out the document inside. I like the feel of the smooth copy paper in my hands. I read it covetously, holding it so the nun sitting next to me can't steal a peek. Its text is as short and as evocative as the purest haiku. " Default judgment is awarded in favor of the plaintiff in the amount of one hundred million dollars." The document is signed by the judge and stamped in red ink and certified by the Prothonotary of the Court of Common Pleas of the City of Philadelphia and legal in every state of the union and those countries with the appropriate treaties with the United States, a group in which, fortunately, Belize is included. One hundred million dollars, the price of two lives plus punitive damages. I bring the paper to my nose and smell it. I can detect the sweet scent of mint, no, not peppermint, government. One hundred million dollars, of which my fee, as the attorney, is a third.

Think hard on that for a moment; I do, constantly. If I find what I'm hunting it would be like winning the lotto every month for a year. It would be like Ed McMahon coming to my door with his grand prize check not once, not twice, but three times, and I would get it all at once instead of over thirty years. It would be enough money to run for president if I were ever so deranged. Well, maybe not that much, but it is still a hell of a lot of money. And I want it, desperately, passionately, with all my heart and soul. Those who whine that there is no meaning left in American life are blind, for there is fame and there is fortune and, frankly, you can take fame and cram it down your throats. Me, I'll take the money.

For almost a year I've been in search of the assets against which my default judgment will be collected. I've traced them through the Cayman Islands to a bank in Luxembourg to a bank in Switzerland, through Liberia and Beirut and back through the Cayman Islands, from where payments had been wired, repeatedly, to an account at the Belize Bank. From the Belize Bank the funds were immediately withdrawn, in cash. Unlike all the other transfers of funds, the transfers to Belize were neither hidden within the entwining vines of larger transactions nor mathematically encrypted. The owner of the money has grown complacent in his overconfidence or he is sending me an invitation and either way I am heading to Belize, flying down to follow the money until it leads me directly to him. He is a vicious man, violent, deceptive, greedy beyond belief. He has killed without the least hesitation, killed for the basest of reasons. His hands drip with blood and I have no grounds to believe he will not kill again. When I think on his crimes I find it amazing how the possibility of so much money can twist one to act beyond all rationality. I am flying down to Belize to find this man in his tropical asylum so I can serve the judgment personally and start the collection proceedings that will at long last make me rich.

In a voice equally apathetic in Spanish and English we are told that we are beginning our approach to Belize City. I return the document to the briefcase, twist the case's lock, stow it back beneath the seat in front of me. Outside the window I see the teal blue of the Caribbean and then a ragged line of scabrous slicks of land, spread atop the water like foul oil, and then the jungle, green and thick and foreign. Clots of treetops are spotted dark by clouds. For not the first time I feel a doubt rise about my mission. If I were going to Pittsburgh or Bern or Luxembourg City I'd feel more confident, but Belize is a wild, untamed place, a country of hurricanes and rain forests and great Mayan ruins. Anything can happen in Belize.

The nun sitting next to me, habited in white with a black veil and canvas sneakers, puts down her Danielle Steel and smiles reassuringly.

"Have you been to our country before?" she asks with a British accent.

"No," I say.

"It is quite beautiful," she says. "The people are wonderful." She winks. "Keep a hand on your wallet in Belize City, yes? But you will love it, I'm sure. Business or pleasure?"

"Business."

"Of course, I could tell by your suit. It's a bit hot for that. You'll be visiting the barrier reef too, I suppose, they all do, but there's more to Belize than fish. While you are here you must see our rain forests. They are glorious. And the rivers too. You brought insect repellent, I expect."

"I didn't, actually. The bugs are bad?"

"Oh my, yes. The mosquito, well, you know, I'm sure, of the mosquito. The malaria pills they have now work wonders. And the welts from the botlass fly last for days but are not really harmful. Ticks of course and scorpions, but the worst is the beefworm. It is the larva of the botfly and it is carried by the mosquito. It comes in with the bite and lives within your flesh while it grows, grabbing hold of your skin with pincers and burrowing in. Nasty little parasite, that. The whole area blows up and is quite painful, there is a burning sensation, but you mustn't pull it, oh no. Then you will definitely get an infection. Instead you must cover the area with glue and tape and suffocate it. The worm squirms underneath for awhile before it dies and that is considered painful by some, but the next morning you can just squeeze the carcass out like toothpaste from a tube."

I am lost in the possibilities when the plane tilts up, passes low over a wide jungle river, and slams into the runway. "Welcome to the Philip Goldson International Airport," says the voice over the intercom. "The airport temperature is ninety three and humidity is eighty-five percent. Enjoy your stay in Belize."

We depart onto the tarmac. It is oppressively hot, the Central American sun is brutal. I feel its pressure all over my body. The air is tropically thick and in its humidity my suit jacket immediately weighs down with sweat. There is something on my face. I am confused for a moment before I realize it is an insect and frantically swipe it away. We are herded in a line toward customs. To our left is the terminal building, brown as rust, a relic from the fifties, to our right is a camouflaged military transport, being loaded with something large I can't identify. A black helicopter circles overhead. Soldiers rush by in a jeep. Sweat drips from my temples and down my neck. I shuck off my jacket, but already my shirt is soaked. I brush a mosquito from my wrist but not before it bites me. I can almost feel something wiggling beneath the skin.

After we hand our passports over for inspection and pick up our bags we are sent in lines to wait for the dog. I sit on my suitcase and pick at the amoebic blob swelling on my wrist. A German shepherd appears, mangy and fierce. He is straining at his leash. He sniffs first one suitcase, then another, then a backpack. The dog comes up to me and shoves his nose into my crotch. Two policemen laugh.

Even inside the terminal it is hot and the sunlight rushing through the windows is fierce and I feel something dangerous beyond the mosquitoes in the swelter about me. I wonder what the hell I am doing in Belize but then I feel the weight of my briefcase in my hand and remember about the hundred million dollars and its story, a story of betrayal and revenge, of intrigue and sex and revelation, a story of murder and a story of redemption and a story of money most of all. Suddenly I know exactly what I am doing here and why.

Chapter Two

It started for me with a routine job in the saddest little room in all of Philadelphia. Crowded with cops and shirtsleeved lawyers and court clerks and boxes of files, a dusty clothes rack, a computer monitor with plastic wood trim and vacuum tubes like something out of Popular Mechanics circa 1954, it was a room heavy with the air of an exhausted bureaucracy. I was sitting alone on the lawyers' bench inside that room, waiting for them to drag my client from the holding cells in the basement. My job that morning was to get him out on a reasonable bail and, considering what he was being charged with, that wasn't going to be easy.

I was in the Roundhouse, Philadelphia Police Headquarters, a circular building constructed in the sixties, all flowing lines, every office a comer office, an architectural marvel bright with egalitarian promise. But the Roundhouse had turned old before its time, worn down by too much misery, too much crime. At the grand entrance on Race Street there was a statue of a cop holding a young boy aloft in his arms, a promise of all the good works envisioned to flow through those doors, except that the entrance on Race Street was now barred and visitors were required to enter through the rear. In through that back entrance, to the right, past the gun permit window, past the bail clerk, through the battered brown doors and up the steps to the benches where a weary public could watch, through a wall of thick Plexiglas, the goings on in the Roundhouse's very own Municipal Court.

"Sit down, ma'am," shouted the bailiff to a young woman who had walked through those doors and was now standing among the benches behind the Plexiglas wall. She was young, thin, a waif with short hair bleached yellow and a black leather jacket. She was either family or friend of one of the defendants, or maybe just whiling away her day, looking for a morning's entertainment. If so, it was bound to be a bit wan. "You can't stand in the back," shouted the bailiff, "you have to sit down," and so she sat.

The defendants were brought into the room in batches of twenty, linked wrist to wrist by steel, and placed in a holding cell, with its own Plexiglas view. You could see them in there, through the Plexiglas, waiting with sullen expectation for their brief time before the bar.

"Sit down, sir," called out the bailiff in what was a steady refrain. "You can't stand back there," and another onlooker dropped onto one of the benches.

"Hakeem Trell," 'announced the clerk and a young man sauntered a few steps to the large table before the bench that dominated the room.

"Hakeem Trell," said Bail Commissioner Pauling, reading from his file, "also known as Roger Pettibone, also known as Skip Dong." At this last alias Commissioner Pauling looked over the frames of his half-glasses at the young man standing arrogantly before him. There was about Hakeem Trell a.k.a. Roger Pettibone a.k.a. Skip Dong the defiant annoyance of a high school student facing nothing more serious than an afternoon's detention. Where was the anxiety as he faced imprisonment, the trembling fear at the rent in his future? What had we done to these children? My client wasn't in the batch they had just brought up and so I was forced to sit impatiently as Commissioner Pauling preliminarily arraigned Hakeem Trell and then Luis Rodriguez and then Anthony O'Neill and then Jason Lawton and then and then and then, one after another, young kids almost all, mainly minority, primarily poor, or at least dressing that way, all taking it in with a practiced air of hostility. Spend enough time in the Roundhouse's Municipal Court and you begin to feel what it is to be an occupying power.

"Sirs, please sit down, you can't stand back there," shouted the bailiff and two men in the gallery arranged themselves on one of the forward benches, sitting right in front of the young blonde woman, who shifted to a different bench to maintain her view of the proceedings.

I recognized both of the men. I had been expecting them to show, or at least some men like them. One was huge, wearing a shiny warm-up suit, his face permanently cast, with the heavy lidded expression of a weightlifter contemplating a difficult squat thrust. I had seen him around, he had grunted at me once. The other was short, thin, looking like a talent scout for a cemetery. He had the face and oily gray hair of a mortician, wearing the same black suit a mortician might wear, clutching a neat little briefcase in his lap. This slick's name was Earl Dante, a minor mob figure I had met a time or two before. His base of operations was a pawnshop, neatly named the Seventh Circle Pawn, on Two Street, south of Washington, just beyond the Mummers Museum, where he made his piranha loans at three points a week and sent out his gap-toothed collectors to muscle in his payments. Dante nodded at me and I contracted the sides of my mouth into an imitation of a smile, hoping no one noticed, before turning back to the goings on in the court.

Commissioner Pauling was staring at me. His gaze drifted up to alight on the multifarious face of Earl Dante before returning back to my own. I gave a little shrug. The clerk called the next name on his sheet.

In the break between batches, Commissioner Pauling strolled off to what constituted his chambers in the Roundhouse, no desk of course, or bookshelves filled with West reporters, but a hook for his robe and a sink and an industrial-sized roll of paper to keep his chamberpot clean. I stepped up to the impeccably dressed clerk still at the bench.

"Nice tie, Henry," I said.

"I can't say the same for yours, Mr. Carl," said Henry, shuffling through his files, not deigning to even check out my outfit. "But then I guess you don't got much selection when you buying ties at Woolworth's."

"You'd be surprised," I said. "I'm here for Cressi. Peter Cressi. Some sort of gun problem."

Henry looked through his papers and started nodding. "Yeah, I'd guess trying to buy a hundred and seventy-nine illegally modified automatic assault weapons, three grenade launchers, and a flamethrower from an undercover cop would constitute some sort of gun problem."

"He's a collector."

"Uh huh," said Henry, drawing out his disbelief.

"No, really."

"You don't gots to lie to me, Mr. Carl. You don't see me wearing robes, do you? Your Cressi will be in the next batch. I know what you want, uh huh. I'll get you out of here soon as I can."

"You're a good man, Henry."

"Don't be telling me, be telling my wife."

They brought up the next batch of prisoners, twenty cuffed wrist to wrist, led into the little holding cell behind the bench upon which I uneasily sat. In the middle of the group was Peter Cressi, tall, curly hair flowing long and black behind his ears, broad shoulders, unbelievably hand- some. His blue silk shirt, black pants, pointed shiny boots were I in stark contrast to the baggy shin-high jeans and hightop sneakers of his new compatriots. As he shuffled through the room he smiled casually at me, as casually as if seeing a neighbor across the street, and I smiled back.

Cressi's gaze drifted up to the benches in the gallery, behind the Plexiglas. When it fell onto Dante's stem face Cressi's features twisted into some sort of fearful reverence.

I didn't like Cressi, actually. There was something ugly and arrogant about him, something uneasy. He was one of those guys who sort of danced while he spoke, as if his bladder was always full to bursting, but you sensed it wasn't his bladder acting up, it was a little organ of evil urging him to go forth and do bad. I didn't like Cressi, but getting the likes of Peter Cressi out of the troubles their little organs of evil got them into was how I now made my living.

I never planned to be a criminal defense attorney, I never planned a lot of things that had happened to my life, like the Soviets never planned for Chernobyl to glow through the long Ukrainian night, but criminal law was what I practiced now. I represented in the American legal system a group of men whose allegiance was not to God and country but to family, not to their natural-born families but to a family with ties that bound so tightly they cut into the flesh. It was a family grown fat and wealthy through selling drugs, pimping women, infiltrating trade unions, and extorting great sums from legitimate industry, from scamming what could be scammed, from loan sharking, from outright thievery, from violence and mayhem and murder. It was the criminal family headed by Enrico Raffaello. I didn't like the work and I didn't like the clients and I didn't like myself while I did the work for the clients. I wanted out, but Enrico Raffaello had once done me the favor of saving my life and so I didn't have much choice anymore.

"All right," said Pauling, back on the bench from his visit to his chambers. "Let's get started."

There were three, prisoners in the column of seats beside where I sat, ready to be called to the bar, and the Commissioner was already looking at the first, a young boy with a smirk on his face, when Henry called out Peter Cressi's name.

"Come on up, son," said Pauling to the boy. Henry whispered in the Commissioner's ear. Pauling closed his eyes with exasperation. "Bring out Mr. Cressi," he said.

I stood and slid to the table.

"I assume you're here to represent this miscreant,, Mr. Carl," said Pauling as they brought Cressi out from, the holding cell.

"This alleged miscreant, yes sir.".

When Cressi stood by my side I gave him a stem look Of reprobation. He snickered back and did his little dance.

"Mr. Cressi," said Commissioner Pauling, interrupting our charming little moment, 11 you are hereby charged with one hundred and eighty-three counts of the illegal purchase of firearms in violation of the Pennsylvania Penal Code. You are also charged with conspiracy to commit those offenses. Now I'm going to read you. the factual basis for those charges, so you listen up." The commissioner took hold of the police report and started reading. I knew what had happened, I had heard all of it that morning when I was woken by a call to my apartment informing me of Cressi's arrest. The arrest must have been something, Cressi with a Ryder truck, driving out to a warehouse in the Northeast to find waiting for him not the crates of rifles and weapons he had expected but instead a squadron of SWAT cops, guns pointed straight at Peter's handsome face. The cops had been expecting an army, I guess, not just some wiseguy with a rented truck.

"Your Honor, with regard to bail," I said, "Mr. Cressi is a lifelong resident of the city, living at home with his elderly mother, who is dependent on his care." This was one of those lawyer lies. I knew Cressi's mother, she was a spry fifty-year-old bingo fiend, but Peter did make sure she took her hypertension medication every morning. "Mr. Cressi has no intention of fleeing and, as this is not in any way a violent crime, poses no threat to the community. We ask that he be allowed to sign his own bail."

"What was he going to do with those guns, counselor? Aerate his lawn?"

"Mr. Cressi is a collector," I said. I saw Henry shaking in his seat as he fought to stifle his laughter.

"What about the flame-thrower?"

"Would you believe Mr. Cressi was having a problem with roaches?"

The commissioner didn't so much as crack a smile, which was a bad sign. "These weapons are illegal contraband, not allowed to be owned by anyone, even so-called 'collectors."

"We have a constitutional argument on that, your honor."

"Spare me the Second Amendment, counselor, please. Your client was buying enough guns to wage a war. Three hundred and sixty-six thousand, ten percent cash," said the Commissioner with a quick pound of his gavel.

"Your Honor, I believe that's terribly excessive."

"Two thousand per weapon seems fair to me. I think Mr. Cressi should spend some time in jail. That's all, next case.

"Thank you, Your Honor," I said, fighting to keep all sarcasm out of my voice. I turned to Earl Dante' sitting patiently on the gallery bench behind the Plexiglas, and nodded at him.

Dante gave a look of resigned exasperation, like he would give to a mechanic who has just explained that his car needed an expensive new water pump. Then the loan shark, followed by the hulk in his workout suit, stood and headed out the gallery's doors, taking his briefcase to the waiting bail clerk. As my gaze followed them out I noticed the thin blonde woman in the leather jacket staring at Cressi and me with something more than idle curiosity.

I turned and gave Cressi a complicated series of instructions. "Keep your mouth shut till you're bailed out, Peter. You got that?"

"What you think, I'm an idiot here?"

"I'm not the one buying guns from cops. Just do as I say and then meet me at my office tomorrow morning so we can figure out where to go, from here. And be sure to bring my usual retainer."

"I always do."

"I'll give you that, Peter." I looked back up to the blonde woman who was still watching us. "You know her?" I asked with a flick of my head to the gallery.

He looked up. "Nah, she's not my type, a scrag like that."

"Then if you don't know her and I don't know her, why's she staring?"

He smiled. "When you look and dress like I do, you know' you get used to it."

"That must be it," I said. "I bet you'll look even more dashing in your orange jumpsuit."

Just then a bailiff grabbed Cressi's arm and started leading him back to the holding cell.

"'See if you can stay out of trouble until tomorrow morning," I said to him as the Commissioner read out another in his endless list of names.

But Cressi was wrong about in whom the blonde was interested. She was waiting outside the Roundhouse for me. "Mr. Carl?"

"That's right."

"Your office said I could find you here."

"And here I am," I said with a tight smile. It was not a moment poised with promise, her standing before me just then. She was in her mid-twenties, small, her bleached hair hacked to ear's length, as if with a cleaver. Black lipstick, black nail polish, mascara globbed around her eyes like a cry for help. Under her black leather was a blue work shirt, originally the property of some stiff named

Lenny, and a thrift-shop-quality pleated skirt. She had five earrings in her right ear and her left nostril was pierced and she looked like one of those impoverished art students who hang outside the Chinese buy-it-by-the-pound buffet on Chestnut Street. A small black handbag hung low from her shoulder. On the bare ankle above one of her black platform shoes was the tattoo of a rose, and that I noticed it there meant I was checking her out, like men invariably check out every woman they ever meet. Not bad, actually. Cressi was right, she was scrawny, and her face was pinched with apprehension, but there was something there, maybe just youth, but something.

"What can I do for you?" I asked.

She looked around. "Can we, like, talk somewhere?"

"You can walk me to the subway," I said as I headed south to Market Street. I wasn't all that interested in what she had to say. From the look of her I had her figured. She had fished my name out of the Yellow Pages and found I was a criminal attorney and wanted me now to help get her boyfriend out of the stir. Of course he was innocent and wrongfully convicted and of course the trial had been a sham and of course she couldn't pay me right off but if I could only help out from the goodness of my heart she would promise to pay me later. About once a week I got just such a call from a desperate relative or girlfriend trolling for lawyers through the phone book. And 'what I told each of them I would end up telling her: that nobody does anything from the goodness of his heart and I was no different.

She watched me go and then ran to catch up, doing a hop skip in her platform shoes to keep pace with my stride. "I need your help, Mr. Carl."

"My docket's full right now."

"I'm in serious trouble."

"All my clients are in serious trouble."

"But I'm not like all your clients."

"That's right, my clients have all paid me a retainer for my services. They have bought my loyalty and attention with their cash. Will you be able to pay me a retainer, Ms.... ?"

"Shaw. Caroline Shaw. How much?"'

"Five thousand for a routine criminal matter."

"This is not routine, I am certain."

"Well in that case it might be more."

"I can pay," she said. "That's not a problem."

I stopped at that. I was expecting an excuse, a promise, a plea, I was not expecting to hear that payment was not a problem. I stopped and turned and took a closer look. Even though she dressed like a waif she held herself regally, her shoulders back, her head high, which was a trick, really, in those ridiculous platform shoes. The eyes within those raccoon bands of mascara were blue and sharply in focus, the eyes of a law student or an accomplished liar. And she spoke better then I would have expected from the outfit. "What do you want me to do for you, Ms. Shaw?"

"I want you to find out who killed my sister."

That was new. I tilted my head. "I thought you said you were in trouble?"

"I think I might be next."

"Well that is a problem, and I wish you well. But you should be going to the police. It's their job to investigate murders and protect citizens, my job is to get the murderers off. Good day, Ms. Shaw," I said as I turned and started again to walk south to the subway.

"I told you I'd be willing to pay," she said as she skipped and hopped again to stay with me, her shoes clopping on the cement walk. "Doesn't that matter?"

"That matters a heap," I said as I kept walking, "but signing a check is one thing, having the check clear is entirely another."

"But it will," she said. "And I need your help. I'm scared."

"Go to the police."

"So you're not going to help me?" Her voice had turned pathetic and after it came out she stopped walking beside me. It wasn't tough to keep going, no tougher than passing a homeless beggar without dropping a quarter in her cup. We learn to just walk on in the city, but even as I walked on I could still hear her. "I don't know what I'm going to do if you don't help me. I think whoever killed her is going to kill me next. I'm desperate, Mr. Carl. I carry this but I'm still scared all the time."

I stopped again and, with a feeling of dread, I turned around. She was holding an automatic pistol pointed at my heart.

"Won't you help me, Mr. Carl? Please? You don't know how desperate I am."

The gun had a black dull finish, rakish lines, it was small-bore, sure, but its bore was still large enough to kill a generation's best hope in a hotel ballroom, not to mention a small-time criminal attorney who was nobody's best hope for anything.

I'll say this for her, she knew how to grab my attention.

Chapter Three

"Put the gun away," I said in my sharpest voice.

"I didn't mean, oh God no, I…" Her hand wavered and the barrel drooped as if the gun had gone limp.

"Put the gun away," I said again, and it wasn't as brave as it sounds because the only other options were to run, exposing my back to the .22 slug, or pissing in my pants, which no matter how intense the immediate relief makes really an awful mess. And after I told her to put the gun away, told her twice for emphasis, she did just as I said, stuck it right back in her handbag, all of which was unbelievably gratifying for me in a superhero sort of way.

Until she started crying.

"Oh no, now don't do that," I said, "no no don't know."

I stepped toward her as she collapsed in a sitting position to the sidewalk, crying, the thick mascara around her eyes running in lines down her cheek, her nose reddening. She wiped her face with a black leather sleeve, smearing everything.

"Don't cry, please please, it will be all right. We'll go somewhere, we'll talk, just please please stop crying, please."

I couldn't leave her there after that, sitting on the ground like she was, crying black tears that splattered on the cement. In a different era I would have offered to buy her a good stiff drink, but this wasn't a different era, so what I offered to buy her instead was a cappuccino. She let me drag her to a coffee shop a few blocks east. It was a beat little place with old stuffed couches and chairs, a few rickety tables, its back walls filled with shelves of musty used paperbacks. I was drinking a black coffee, decaf actually, since the sight of her gun aimed at my heart had given me enough of a start for the morning. Caroline was sitting across from me at one of the tables, her arms crossed, in front of her the cappuccino, pal, frothy, sprinkled with cinnamon, and completely untouched. Her eyes now were red and smeared and sad. There were a few others in the joint, young and mangy in their slacker outfits, greasy hair and flannel shirts, sandals. Caroline looked right at home. In my blue suit I felt like a narc.

"Do you have a license for that gun?" I asked.

"I suppose I need one, don't I?"

I nodded and took a sip from my mug. "Take some sound legal advice and throw the gun away. I should turn you in, actually, for your own good, though I won't. It goes against my…"

"You don't mind if I smoke, do you?" she said, interrupting me mid-sentence, and before I could answer she was already rummaging again in that little black handbag. I must admit I didn't like seeing her hand back inside that bag, but all she brought out this time was a pack of Camel Lights. She managed to light her cigarette with her arms still crossed.

I looked her over again and guessed to myself that she was a clerk in a video store, or a part-time student at Philadelphia Community College, or maybe both. "What is it you do, Caroline?"

"I'm between things at the moment," she said, leaning forward, looking for something on the table. Finding nothing, she tossed her spent match atop the brown sprinkled foam of her cappuccino. I had just spent $2.50 for her liquid ashtray. I assumed she would have preferred the drink. "Last month I was a photographer. Next month maybe I'll take up tap dancing."

"An unwavering commitment to caprice, I see."

She laughed a laugh so full of rue I felt like I was watching Betty Davis tilt her head back, stretch her white neck. "Exactly. I aspire to live my life like a character in a sitcom, every week a new and perky adventure."

"What's the title of this episode?

"Into the Maw, or maybe Into the Mall, because after this I need to go to the Gallery and buy some tampons. Why were you in that stupid little courtroom this morning?"

I took another sip of coffee. "One of my clients attempted to buy one hundred and seventy-nine automatic rifles, three grenade launchers, and a flamethrower from an undercover cop."

"Is he in the mob, this client of yours?"

"There is no mob. It is a figment of the press's imagination."

"Then what was he going to do with all those guns?"

"That's the question, isn't it?"

"I had heard you were a mob lawyer. It's true, isn't it?"

I made an effort to stare at her without blinking as I let the comment slide off me like a glob of phlegm.

Yes, a majority of my clients just happened to be junior associates of Mr. Raffaello, like I said, but I was no house counsel, no mob lawyer. At least not technically. I merely handled their cases after they allegedly committed their alleged crimes, nothing more. And though my clients never flipped, never ratted out the organization that fed them since they were pups, that sustained them, that took care of their families and their futures, thought my clients never informed on the family, the decision no to inform was made well before they ever stepped into my office. And was I really representing these men, or was I instead enforcing the promises made to all citizens in the Constitution of the United States? Wasn't I among the noblest defenders of those sacred rights for which our forefathers fought and died? Who among us was doing more to protect liberty, to ensure justice? Who among us was doing more to safeguard the American way of life?

Do I sound defensive?

I was about to explain it all to her but it bored even me by then so all I said was, "I do criminal law. I don't get involved in…"

"What's that?" she shouted as she leaped to kneeling on her seat. "What is it? What?"

I stared for a moment into her anxious face, filled with a true terror, before I looked under the table at where her legs had been only an instant before. A cat, brown and ruffled, was rubbing its back on the legs of her chair. It looked quite contented as it rubbed.

"It's just a cat," I said.

"Get rid of it."

"It's just a cat," I repeated.

"I hate them, miserable, ungrateful little manipulators, with their claws and their teeth and their fur-licking tongues. They eat human flesh, do you know that? It's one of their favorite things. Faint near a cat and it'll chew your face off."

"I don't think so."

"Get rid of it, please please please."

I reached under the table and the cat scurried away from my grasp. I stood up and went after it, herding it to the back of the coffee shop where, behind the bookshelves was an open bathroom door. When the cat slipped into the bathroom I closed the door behind it.

"What was that all about?" I asked Carline when I returned to the table.

"I don't like cats," she said as she fiddled with her cigarette.

"I don't especially like cats either, but I don't jump on my seat and go ballistic when I see one."

"I have a little problem with them, that's all."

"With cats?"

"I'm afraid of cats. I'm not the only one. It has a name. Ailurophobia. So what? We're all afraid of something."

I thought on that a bit. She was right of course, we were all afraid of something, and in the scheme of things being afraid of cats was not the worst of fears. My great fear in this life didn't have a name that I knew of. I was afraid of remaining exactly who I was, and that phobia instilled a shiver of fear into every one of my days. Something as simple as a fear of cats would have been a blessing.

"All right, Caroline," I said. "Tell me about your sister."

She took a drag from her cigarette and exhaled in a long white stream. "Well, for one thing, she was murdered."

"Have the police found the killer?"

"She reached for her pack of Camel Lights even though the cigarette she has was still lit. "Jackie was hanging from the end of a rope in her apartment. They've concluded that she hung herself."

"The police said that?"

"That's right. The coroner and some troglodyte detective named McDeiss. They closed the case, said it was a suicide. But she didn't."

"Hang herself?"

"She wouldn't."

"Detective McDeiss ruled it a suicide?"

She sighed. "You don't believe me either."

"No, actually," I said. "I've had a few run-ins with McDeiss but he's a pretty good cop. If he said it was a suicide, it's a fair bet your sister killed herself. You may not have thought she was suicidal, that's perfectly natural, but…"

"Of course she was suicidal," she said, interrupting me once again. "Jackie read Sylvia Plath as if her poetry were some sort of road map through adolescence. One of her favorite lines was from a poem called 'Lady Lazarus.' 'Dying is an art, like everything else. I do it exceptionally well.'"

"Then I don't understand your problem."

"Jackie talked of suicide as naturally as others talked of the weather, but she said she'd never hang herself. She was disgusted by the idea of dangling there, aware of the pain, turning as the rope tightened and creaked, the pressure on your neck, on your backbone, hanging there until they cut you down."

"What would have been her way?"

"Pills. Darvon. Two thousand milligrams is fatal. She always had six thousand on hand. Jackie used to joke that she wanted to be prepared if ever a really terrific suicidal urge came along. Besides, in her last couple years she almost seemed happy. It was like she was actually finding the peacefulness she once thought was only for her in death through this New Age church she had joined, finding it through meditation. She had even gotten herself engaged, to an idiot, yes, but still engaged."

"So let's say she was murdered. What do you want me to do about it?"

"Find out who did it."

"I'm just a lawyer," I said. "What you're looking for is a private investigator. Now I have one that I use who is terrific. His name is Morris Kapustin and he's a bit unorthodox, but if anyone can help he can. I can set…"

"I don't want him, I want you."

"Why me?"

"What exactly do mob lawyers do, anyway, eat in Italian restaurants and plot?"

"Why me, Caroline?" I stared at her and waited.

She lit her new cigarette4 from the still-glowing butt of her old one and then crushed the old against the edge of the mug. "Do you think I smoke too much? Everybody thinks I smoke too much. I used to be cool, now it's like I'm a leper. Old ladies stop me in the street and lecture."

I just stared at her and waited some more and after all the waiting she took a deep drag from her cigarette, exhaled, and said:

"I think a bookie named Jimmy Vigs killed her."

So that was it, why she had chased me, insignificant me, down the street and pulled a gun and collapsed to the cement in black tears, all of which was perfectly designed to gain my attention, if not my sympathy. I knew Jimmy Vigs Dubinsky, sure I did. I had represented him on his last bookmaking charge and gotten him an acquittal too, when I denied he was a gambler, denied it was his ledger that the cops had found, denied it was his handwriting in the ledger despite what the experts said because wink-wink what do experts know, denied the notes in the ledger referred to bets on football games, denied the units mentioned in the ledger notes referred to dollar amounts, and then, after all those sweet denials, I had opened my arms and said with my best boys-will-be-boys voice, "And where's the harm?" It helped that the jury was all men after I had booted all the women, and that the trial was held in the spring, smack in the middle of March madness, when every one of those men had money in an NCAA pool. So, yes, I knew Jimmy Vigs Dubinsky.

"He's a sometime client, as you obviously know," I said, "so I really don't want to hear anymore. But what I can tell you about Jim Dubinsky is that he's not a killer. I've known him for…"

"Then you can clear him."

"Will you stop interrupting me? It's rude and annoying."

She tilted her head at me and smiled, as if provoking me was her intent.

"I don't need to clear Jimmy," I said. He's not a suspect since the cops, ruled your sister's death a suicide."

"I suspect him and I have a gun."

I pursed my lips. "And you'll kill him if I don't take the case, is that it?"

"I'm a desperate women, Mr. Carl," she said, and there was just the right touch of husky fear in her voice, as if she had prepared the line in advance, repeated it to the mirror over and over until she got it just right.

"Let me guess, just a wild hunch of mine, but before you started playing around with f-stops and film speeds, did you happen to take a stab at acting."

She smiled. "For a few years, yes. I was actually staring in a film until financing was pulled."

"And that point the gun, 'Oh-my-God' collapse into a sobbing heap on the sidewalk thing, that was just part of an act?"

Her smile broadened and there was something sly and inviting in it. "I need your help."

"You made the right decision giving up on the dramatics." I thought for a moment that it might be entertaining to see her go up against Jimmy Vigs with her pop gun, but then thought better of it. And I did like that smile of hers, at least enough to listen. "All right, Caroline, tell me why you think my friend Jimmy killed your sister."

She sighed and inhaled and sprayed a cloud of smoke into the air above my face. "It's my brother Eddie," she said. "He has a gambling problem. He bets too much and he loses too often. From what I understand, he is into this Jimmy Vigs person for a lot of money, too much money. There were threatening calls, there were late-night visits, Eddie's car was vandalized. One of Eddie's arms was broken, in a fall, he said, but no one believed him. Then Jackie died, in what seemed like a suicide but which I know wasn't and suddenly the threats stopped, the visits were finished, and Eddie's repaired and repainted car maintained its pristine condition. The bookie must have been paid off. If this Jimmy Vigs person had killed Eddie he would have lost everything, but he killed Jackie and that must have scared Eddie into digging up the money and paying. But I heard he's betting again, raising his debt even farther. And if your Jimmy Vigs needs to scare Eddie again I'm the one he'll go after next."

I listened to her, nodding all the while, not believing a word of it. If Jimmy was stifled he'd threaten, sure, who wouldn't, and maybe break a leg or two, which could be quite painful when done correctly, but that was as far as it would go. Unless, maybe, we were talking at big big bucks, but it didn't seem likely that Jim would let it get that high with someone like this girl's brother.

"So what I want," she said, "is for you to find out who killed her and get them to stay away from me. I thought with your connections to this Jimmy Vigs and the mob it would be easy for you."

"I bet you did," I said. "But what if it wasn't Jimmy Vigs?"

"He did it."

"Most victims are killed by someone they know. If she was murdered, maybe it was by a lover or a family member?"

"My family had nothing to do with it," she said sharply.

"Jimmy Dubinsky is not a murderer. The mere fact that your brother owed him money is…"

"Then what about this?" she said while she reached into her handbag.

"You did it again, dammit. And I wish you wouldn't keep putting your hand in there."

"Frightened?" She smiled as she pulled out a plastic sandwich bag and dangled it before me.

I took the bag from her and examined it. Inside was a piece of cellophane, a candy wrapper, one end twisted, the other opened and the word "Tosca's" printed on one side. When I saw the printing my throat closed on me.

"I found this lying on her bathroom floor, behind the toilet, when I was cleaning out her apartment," she said.

"So she had been to Tosca's. So what?"

"Jackie was an obsessive cleaner. She wouldn't have just left this lying about. The cops missed it, I guess they don't do toilets, but Jackie surely wouldn't have left it there. And tomato sauce was too acidic for her stomach. She never ate Italian food."

"Then someone else, maybe."

"Exactly. I asked around and Tosca's seems to be some sort of mob hangout."

"So they say."

"I think she was murdered, Mr. Carl, and that the murderer had been to Tosca's and left this and I think you're the one who can find out for me."

I looked at the wrapper and then at Caroline and then back at the wrapper. Maybe I had underestimated the viciousness of Jimmy Vigs Dubinsky, and maybe one of my clients, in collecting for my other client, had left this little calling card from Tosca's at the murder scene.

"And if I find out who did it," I said, "then what?"

"I just want them to leave me alone. I f you find out who did it, could you get them to leave me alone?"

"Maybe," I said. "What about the cops?"

"That will be up to you," she said.

I didn't like the idea of this waif rummaging through Tosca's looking for trouble and I figured Enrico Raffaello wouldn't like it much either. If I took the retainer and proved to her, somehow, that her sister actually killed herself, I could save everyone, especially Caroline, a lot of trouble. I took another look at the wrapper in that plastic bag, wondered whose fingerprints might still be found there, and then stuffed it into my jacket pocket where it could do no harm.

"I'll need a retainer of ten thousand dollars," I said.

She smiled, not with gratitude but with victory, as if she knew all along I'd take the case. "I thought it was five thousand."

"I charge eighty-five an hour plus expenses."

"That seems very high."

"That's my price. And you have to promise to throw that gun away."

She pressed her lips together and thought about it for a moment. "But I want to keep the gun," she said, with a slight put in her voice. "It keeps me warm."

"Buy a dog."

She thought some more and then reached into her handbag once again and this time what she pulled out was a checkbook, opening it with the practiced air you see in well-dressed women at grocery stores. "Who should I make it out to?"

"Derringer and Car," I said. "Ten thousand dollars."

"I remember the amount," she said with a laugh as she wrote.

"Is this going to clear?"

She ripped the check from her book and handed it to me. "I hope so."

"Hopes have never paid my rent. When it clears I'll start to work." I looked the check over. It was drawn on the First Mercantile Bank of the Main Line. "Nice bank," I said.

"They gave me a toaster."

"And you'll get rid of the gun?"

"I'll get rid of the gun."

So that was that. I took her number and stuffed the check into my pocket and left her there with a cigarette smoldering between her fingers. I had been retained, sort of, assuming the check cleared, to investigate the mysterious death of Jacqueline Shaw. I had expected it would be a simple case of checking the files and finding a suicide. I didn't know then, couldn't possibly have known, all the crimes and all the hells through which that investigation would lead. But just then, with that check in my hand, I wasn't thinking so much about poor Jacqueline Shaw hanging by her neck from a rope, but instead about Caroline, her sister, and the slyness of her smile.

I took the subway back to Sixteenth Street and walked the rest of the way to my office on Twenty-first. Up the stairs, past the lists of names, through the hallway with all the other offices with which we shared our space, to the three doorways in the rear.

"Any messages, Ellie?" I asked my secretary. She was a young blonde woman with freckles, our most loyal employee as she was our only employee.

She handed me a pile of slips. "Nothing exciting."

"Is there ever?" I said as I nodded sadly and went into my scuff of an office. Marked with white walls, files piled in lilting towers, dead flowers drooping like desiccated corpses from a glass vase atop my big brown filing cabinet. Through the single window was a sad view of the decrepit alleyway below. I unlocked the file cabinet and dropped the plastic bag with the Tosca's candy wrapper inside into a file marked "Recent Court Decisions." I closed the drawer and pushed in the cabinet lock and sat at my desk, staring at all the work I needed to do, transcripts to review, briefs to write, discovery to discover. Instead of getting down to work I took the check out of my pocket. Ten thousand dollars. Caroline Shaw. First Mercantile Bank of the Main Line. That was a pretty fancy banking address for a punkette with a post in her nose. I stood and strolled into my partner's office.

She was at her desk, chewing, a pen in one hand and a carrot in the other. Gray-and-white-streaked copies of case opinions, paragraphs highlighted in fluorescent pink, were scattered across her desktop and she stared up at me as if I were a rude interruption.

"What's up, doc?" Beth Derringer said.

"Want to go for a ride?"

"Sure," she said as she snapped a chunk of carrot with her teeth. "What for?"

"Credit check."

Excerpted from BITTER TRUTH by William Lashner. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced without written permission from HarperCollins Publishers, 10 East 53rd Street, New York, NY 10022