Excerpt

Excerpt

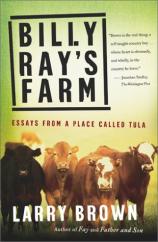

Billy Ray's Farm

Prologue

A long time ago when I was a boy, there was one slab of concrete that stretched from Oxford to Toccopola, a distance of about sixteen miles, and that was the road everybody used to get to town. It was kind of like half of a road, with one side concrete, the other side dirt and gravel. If you were heading to town, you could stay on the concrete all the way and never have to get off on the gravel side. And if you were coming from town, you could get on the concrete part and drive on the wrong side of the road until you met somebody, and then you had to jump back onto the gravel.

That road has been gone for a long time, but I still remember the swaying of the car as my father went from one side of the road to the other. Everybody did it and nobody ever thought anything about it.

A trip to town on Saturday was a big event. The Square in Oxford has changed some, true, but by and large it still retains the image I have of it from thirty years ago. It is still lined with stores and parked cars, and the big oaks still stand on the courthouse lawn, and the Confederate soldier is still standing there high above everything so that you can see him first when you come up the long drive of South Lamar. What has changed is the nature of the town. A long time ago you could find people selling vegetables from the backs of their trucks, and you could go in Winter's Cafe and get a hamburger and a short-bottled Coke for sixty-five cents. You can't even buy an Egg McMuffin on University Avenue for that.

Faulkner would probably be flabbergasted to know that there are several bars on the Square now, and that blues music can often be heard wailing out of the open doors on hot summer nights, floating around the air on the Square, lifting up to the balconies of the apartments that line the south side, where people are having drinks and conversing. It's not like it was when he was around. Life was hard for some. Blacks were oppressed. The drinking fountains on the Square were labeled Colored and White. That world doesn't exist anymore.

What does exist is the memory of it, a faded remnant of the way things were. Write about what you know, yes, even if it doesn't exist anymore.

When I wrote my novel Father and Son, people wondered why I set it back in the sixties. The answer to that is very simple. When I wrote the first scene, where Glen Davis and his brother Puppy are driving back into town, I didn't see the Square I see now, with Square Books on the left side of South Lamar and Proud Larrys' on the right. I saw that old Oxford, the one where Grace Crockett's shoe store stood in the place now occupied by a restaurant and bar called City Grocery, and I saw the old trucks with wooden roofs built over the back ends to shield the watermelons and roasting ears and purple hull peas from the heat of the sun, and I saw a battered old dusty car that my two characters were riding in, and I knew that it had a shift on the column, and an AM radio with push buttons, and musty upholstery that had once been velvet. I saw all that and I knew that they had driven in one hot Saturday afternoon back during my childhood, and I remember the way things were.

What is it about Oxford that produces writers? I get asked that question a lot, and so does Barry Hannah, and so does John Grisham, and I have to confess that I'm just as bewildered by that question as the people who continue to ask it. Maybe even more so. They always want to ask about Faulkner and what it all means, being a writer in Oxford, and where all the stories come from, and why that environment seems to nurture writers. No matter where I go, I always get hit with that question or a variation of it.

I don't know what the answer is for anybody else, and I don't know what caused Faulkner to write. Most times, for any writer, I think it springs from some sort of yearning in the breast to let things out, to say something about the human condition, maybe just to simply tell a story. When pressed really hard, I say something generic like, "Well, for me the land sort of creates the characters, you know? I mean I look at the people around me and wonder what their stories are, or I think of some character and put him in a situation and then follow him around for a while, see what happens next."

It's hard sometimes while being pressed into a corner of the wallpaper to come up with a satisfying answer about your own land and the influences it has on you. Most of this stuff is private. You could say that you like the way the sky looks just before a big thunderstorm moves across a river bottom, or that you like to see the thousands of tiny frogs that emerge on the roads on a balmy spring night just after a good shower. You could ruminate expansively about the beauty of a hardwood forest on a cold morning, or the way the distant trees stand shimmering against the horizon on a blistering summer day. But none of that would satisfy the question. What is it they really want to know? Probably nothing more than that old and tired favorite: Where do you get your ideas?

I believe that writers have to write what they know about. I don't think there's much choice in that. The world Faulkner wrote about was vastly different from the one that exists now. If Faulkner were alive today, he would see that. The mansion down the street has been replaced by a BP gas station now, and the hardwood forest the dogs once yammered through has been clear-cut and turned into a pine plantation. Black folks don't say "yassuh" any more, and at this moment I would have no idea where in all of Lafayette County I could find a good mule. I think the past influenced Faulkner a lot. It must have, since so many of his stories and novels are about segments of history that had already passed when he wrote of them. All he was doing was what every other writer does, and that is drawing upon the well of memory and experience and imagination that every writer pulls his or her material from. The things you know, the things you have seen or heard of, the things you can imagine. A writer rolls all that stuff together kind of like a taco and comes up with fiction. And I think whatever you write about, you have to know it. Concretely. Absolutely. Realistically.

Oxford produces writers for the same reason that New York does, or Knoxville, or Milledgeville, or Bangor. You can't pick where you're born or raised. You take what you're given, whether it's the cornfields of the Midwest or the coal mines of West Virginia, and you make your fiction out of it. It's all you have. And somehow, wherever you are, it always seems to be enough.

Excerpted from BILLY RAY'S FARM © Copyright 2002 by Larry Brown. Reprinted with permission by Touchstone. All rights reserved.

Billy Ray's Farm

- Genres: Nonfiction

- paperback: 224 pages

- Publisher: Touchstone

- ISBN-10: 0743225244

- ISBN-13: 9780743225243