Excerpt

Excerpt

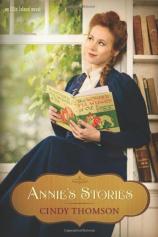

Annie's Stories: An Ellis Island Novel

Chapter 1

Late August, 1901

Sometimes the smallest things ignited memories Annie Gallagher would sooner forget. This time all it took was a glimpse of a half-finished tapestry Mrs. Hawkins had left on her parlor chair: Home Sweet Home. Annie pressed her palm against her heart, trying to shut out the realization that she was far from home—and not just because she now lived in America.

In a few days it would be her birthday, but she wanted to forget. Birthdays held no significance when your parents had gone to heaven.

For most of her life Annie had traveled with her father, a seanchaí, a storyteller from the old Irish tradition. She had learned the age-old stories of the great warrior Cuchulain and the tragic tale of a cruel stepmother in “The Children of Lir.” She learned of kings and monks and lords and wild beasts. But when night came and he tucked her into whatever straw cot they had borrowed for the night, he told her tales that were just for her—Annie’s stories, he called them. Now that her father was gone, those stories were all she had, her only connection to a place, intangible as it might have been, that she called home.

She held on to them, brought them out from time to time to remind her she’d once lived in someone’s heart. Without that, she feared she might plunge again into darkness.

Annie approached the breakfront cabinet gracing the wall opposite a substantial parlor window that looked out to the street. She opened the door, revealing her special lap desk. Suddenly her father’s voice lived again in her mind.

“Look here, Annie lass,” her da called one day from his mat by Uncle Neil’s hearth. Neil O’Shannon was her mother’s brother, and he hadn’t wanted Annie and her father in his home, but her father—who was just as dismayed to be there but had found no other open hearth in that sparsely populated countryside—had been too ill to move on.

Annie had just come inside from gathering seaweed on the shore. She set her reed basket on the table and came closer. Da held a box of some sort.

“See here. ’Tis a writing desk—pens and even paper inside.” He opened the box and showed her how the top folded into a writing surface.

“I’ve never seen anything like it.” Annie rubbed her hand across the inlaid design on the edges. Swirls, flowers—so beautiful.

“I should write down your tales for you.”

“Which ones, Da?” She examined the ink pot. Full.

“Why, Annie’s stories, darlin’. Those that are yours. I won’t be here forever to tell them to you.”

She shook her head. “Don’t talk like that, Da. And don’t you know, I won’t be forgetting them.”

“Don’t suppose you will. But I’ll write them just the same. I’ll add some drawings. You’d like that, so.”

She had not thought he’d done it, not until after he’d passed on and Father Weldon helped her find those pages, those precious hand-scribed stories, the day he’d rescued her from that evil Magdalene Laundry, a prison-like place for young girls who had committed no crime except being homeless and unwanted.

She sat down on the piano stool in Mrs. Hawkins’s parlor as the memories flooded her mind like a swarm of midsummer gnats. She heard Father Weldon’s voice. “Hold on to the good memories. The Magdalene Laundry you were in does not speak for the church, child. There are those who are compassionate, even within its walls, but they allow fear to overshadow what’s right. I implore you to focus on the good now, the good you have seen among my parishioners. And know that God will provide,” he had said.

Perhaps Father Weldon had been right about the laundry. The church wasn’t evil. Sister Catherine and a couple of the other nuns seemed to care. But Annie was sure God had not been in that laundry. God couldn’t be bothered, she’d realized.

“Don’t give Neil O’Shannon a second thought, child,” Father Weldon had told her, his eyes soft. “Your father was a remarkable man. You have your memories now, don’t you?”

Painful memories she could not forget. Not so far.

Her sorrow had begun on a day in January in the year nineteen hundred, the day they’d buried her father.

“A wanderer is only at home in the hearts of those who love him.”

Annie had heard her father say this, and now that he was gone, Annie had no place in the world. She had been born of a great love between two people separated by hatred, as tragic a tale as Romeo and Juliet.

She had heard the story from her father many times. Annie’s parents had fallen in love, but the O’Shannons did not want their daughter to marry a Protestant, especially a seanchaí. But they’d done it anyway, run off to Dublin, where an Anglican minister married them. A month later, while her father and mother traveled on the road to Limerick, Annie’s mother’s family tracked her down, locked Annie’s father in a cowshed, and then stole her mother away. After some time, her father found her mother, but tragically she died in childbirth, and from then on, it had only been Annie and her father.

Now, just Annie.

“Marty Gallagher was a magnificent storyteller,” the priest had said to those gathered in the churchyard. “Not only could he recite entire Shakespearean plays by memory, but he told his own tales as well. Many of you gathered here were privileged to be entertained by him.”

A man she didn’t know—but was told was Mr. Barrows from Dublin—had approached her after prayers were said. “My deepest sympathies, Miss Gallagher.”

She thanked him, but his condolences seemed to slide right by. There was nothing anyone could have said to make that better.

“The entire world will mourn his passing.” He extended his black umbrella over his dipped head and backed away.

People say all kinds of odd things when someone dies. Paying respects at a funeral was fine and good for that man, whoever he had been. He’d gone back to Dublin and carried on. But Annie? She was only twenty years of age, and her life spread out before her now like a long, lonely highway spilling into distant hills beyond where the eye can see.

It was what had happened after the funeral that had led to her imprisonment in that unspeakable place.

She rose now, shut the door to the breakfront, and wiped it down, though she’d noted no dust. Glancing out the front window at the pedestrians populating Lower Manhattan’s sidewalks, she observed men carrying large black satchels. Businessmen. Not a seanchaí in the lot, she supposed. If she ever married, it would be to someone who appreciated the power of a story.

Sighing, Annie brushed her feather duster along the windowsill and the glass globes of the oil lamps. How she’d come to be the housekeeper at Hawkins House was by chance, a stroke of incredible luck, to be sure. Father Weldon had sent her there.

“I will arrange for a woman named Agnes Hawkins to take you in. She and her charity supporters are opening a home for girls in New York, and she needs a housekeeper to help her get started.”

“Why would you do this for me, Father?”

This man, a British priest in the west of Ireland, was such an oddity. Even Da in his storytelling could not have created such an unlikely rescuer.

“I had great admiration for your father, Annie. He was a fine man, God rest his soul. Being a storyteller, he wandered, going from place to place to do his work. In a small way I’m like he was. I am in a foreign land. My sister, the woman who will take you in, is as well. But God directs our paths. We don’t always end up in the places we’d imagined. I’m to see you get away from here safely and begin life anew with hope.”

Annie knew as well as winter follows autumn that God had not directed her. If he had, he never would have allowed her to end up in that horrible laundry. Without her father, without God, Annie was adrift on a dark, choppy sea. She’d hoped living in America at Hawkins House would lead her out of the nefarious hole she’d been plunged into since her father died, and it had been a fortuitous beginning. Mrs. Hawkins was nice, and Annie truly was grateful to her. But her father had said home is where the people who love you are, the people who truly want you. He had not said home was where people were just nice to you.

Annie had been fortunate to come here, indeed. However, everyone knew luck ran out. There were many chapters of Annie’s life yet to be written. No one in Ireland had believed Annie capable of directing her own destiny. But now? Now she needed to make her own way without Da . . . and without even God’s help.

Annie's Stories: An Ellis Island Novel

- Genres: Christian, Christian Fiction, Fiction, Historical Fiction

- paperback: 416 pages

- Publisher: Tyndale House Publishers, Inc.

- ISBN-10: 1414368453

- ISBN-13: 9781414368450