Excerpt

Excerpt

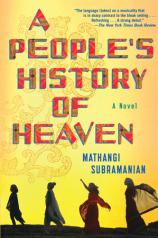

A People's History of Heaven

“Padma? Padma, where are you?”

“Amma?” Padma springs up from where she’s sitting with the rest of us, crouched in front of steaming plates of biryani.

“Where is everyone?” Gita Aunty asks. “Why isn’t anyone home?”

“We’re all out here, Amma,” Padma says. “There’s been some trouble.”

“Trouble?” Gita Aunty says. Rubs her eyes with the back of her hand. “What trouble?”

“First, eat,” Padma says. “Then I’ll tell you.”

Ourmothers are brassy and cheerful, larger than life. Fill up space with their bodies, their orders. Their noise. Padma’s mother, though? She doesn’t take up any space at all. Floats through Heaven like a silhouette. An outline of someone who once was, a charcoal pencil sketch smudged around the edges.

Padma’s mother is nothing like our mothers. But Padma says she used to be.

“Did you feed the crows?” Gita Aunty asks. “They’ll be hungry.”

“I will, Amma. Right now it’s dinnertime, okay?” Padma says. Steers Gita Aunty around the bulldozers, away from the line of engineers loading up the bus. Settles her mother on the ground, pours water over her hands to wash off the dirt. The way our teachers did when we were in preschool. Before we knew how to take care of ourselves.

Banu scurries over with a plate of biryani and a water bottle. Hands them to Padma, who hands them to her mother.

“Eat, Amma,” Padma says. “You need your strength.”

Beneath the glow of the rising moon, streetlamps flicker and headlights glimmer, fireflies twinkle and cell phones gleam. The foreign lady’s camera flashes, illuminating Padma stroking her mother’s back, Banu curling her shoeless toes. Gita Aunty hunching over her meal, next to the space where Banu’s ajji would be if she wasn’t too sick to eat.

Heaven may be striped with all kinds of light tonight. But it’s the line between the mothered and the unmothered that always glows the brightest.

After she gives birth to Padma’s youngest brother, Gita Aunty can’t stop crying. She cries when she hangs the laundry on the clothesline strung between the roofs of Heaven’s houses. When she pours the dosa for breakfast, packs the rice for tiffin. Even cries when she sees Padma, even though Padma is the only one who makes her happy.

“Why’s your amma so sad?” Rukshana asks.

“She misses the village,” Padma tells us.

“What’s there to miss in the village?” Joy asks. The way she says it, you can tell she doesn’t want an answer.

“The colors,” Padma says. “Especially the blues and greens.”

“There’s blue here. Green too,” Joy says, pointing to the blue-and-white city bus rumbling by, the peeling green paint on the Dumpsters they installed behind the school.

“Those aren’t the greens and blues she misses,” Padma says. “She misses other colors. Not those.”

“What nonsense,” Rukshana says. “Green is green and blue is blue.”

Padma shakes her head and says, “There’s sky blue, river blue. Peacock-neck blue and God-skin blue. Even sky blue is so many blues. There’s a sky blue that smells like rain. There’s one that smells like drought. Green is like that too. Rice-paddy green, bitter-gourd green, parrot-tail green. You don’t know about them because in Bangalore, you don’t have them. Those are the colors my mother misses.”

Padma’s eyes are full of fear. But they’re full of something else too. Something the rest of us wish we had. A memory of air that isn’t salty with petrol and construction dust. Of roads lit by stars instead of the headlights of two-wheelers. Of river mud and thunderstorms and beetle wings we’ll never feel against our toes, our cheeks. The palms of our hands.

There is city smart and there is country smart. One day, Padma will be both. But we will only ever be one.

Still, Rukshana says, “All that jungly stuff is well and good, but it won’t get you anywhere here.”

“That jungly stuff is exactly what she misses,” Padma says. Like she hasn’t heard right. Or like she’s heard right, but she’s answering wrong. “She misses the birds.”

<SEC>

Before we met Padma, we always took the short way home. Through narrow gallis where skinny-shouldered men push wooden carts full of guavas, cucumbers, chili, and salt. Where village women hack open tender coconuts with machetes, sunlight bouncing off the jewels in their twice-pierced noses. Where city women crouch on straw mats heaped with vegetables, herbs, fruits, calling out, “Carrots! Bananas! Cilantro! Beans!”

Padma makes us take the long way home. Starts in the alleyway behind the school. Weaves through piles of plastic milk bags and cow dung and rotting vegetables. Opens into the posh neighborhood full of three-story houses with gardens full of roses and carnations, driveways full of cars, entire floors to rent to strangers.

Or, in one house, an entire veranda just for birds.

There are plenty of birds in Bangalore. Mynahs with feathers the color of mud. Pigeons with necks that pop like rusty bed springs. Kites that carry pieces of rotting flesh in their city-sharpened claws.

These are not those kinds of birds. These birds are the colors of the jewels in the Joyalukka’s window. These birds are so posh that if they applied for visas at the American embassy, they would get them on the first try.

When she sees the house, Padma dusts off her skirt, tucks in her shirt. Licks her palm, smooths down her hair. Walks right up to the door and rings the doorbell.

“Madam,” she says to the lady who answers. A lady dripping in actual jewels from the actual window of Joyalukka’s. “Do you need a maid?”

“In fact, I do,” the lady says. Words pleated like she hired the ironwallah to press her tongue. “But you’re a bit young, aren’t you, darling?”

“Not me, madam,” Padma says. “My mother. Her name is Gita.”

“Is she neat and clean like you?” the lady asks.

“Yes,” Padma says. “And she has impeccable manners.”

Where did Padma learn a word like that? We can’t help but be impressed. The lady is too, because she says, “Bring your mother tomorrow, darling. She must be a decent woman if she raised a girl like you.”

<SEC>

On her mother’s first day of work, Padma wakes her early. Makes her apply the tiniest bit of kohl to hide the dark circles under her eyes, wear the sari Padma has washed and dried and pressed the night before. Holds Gita Aunty’s hand as they cross the footbridge, taking a left instead of going straight. As they plunge into the rich neighborhoods, memories of rivers and farms trace watery tributaries on Gita Aunty’s cheeks.

Inside the house, the hall hums with whirring ceiling fans, with wind rushing between open windows. The floor is lined with earthen pots full of tall, feathery plants, the walls with tasteful tribal art. The air is still buttery with the smell of the alu parathasand yogurt the family had for breakfast.

“The work is nothing difficult,” the pressed-tongue woman says, gesturing for Padma and Gita Aunty to follow her up the stairs. “We have a girl to do the chopping and cooking. Another girl for the clothes. The mali comes for the plants. We’d need you only for some sweeping and dusting and tidying up. And then, of course, we need you to care for the birds.”

“The birds?” Gita Aunty whispers.

“I hope you don’t mind?” the pressed-tongue woman says, giving the door at the top of the stairs the slightest push. It glides on its hinges, like it’s recently been oiled.

Padma and her mother step out onto a veranda wrapped in wooden boards and chicken wire. The air flashes with feathers, beaks, throats, wings. Wooden perches and baskets of seeds hang from the ceiling, swinging back and forth as birds land, pause, take flight. The air smells of ammonia and grain.

“You’ll need to clean this and feed them twice a day,” the pressed-tongue lady says. “We only get the best organic feed. Oh, and don’t forget to make sure they always have water. From the dispenser, not the tap.”

Padma bites the inside of her cheek to keep from laughing. No one in Heaven would waste money on a bottle of Bisleri branded water, let alone a whole twenty-liter can a week just for birds.

“Would you mind, madam,” Gita Aunty asks, “if I sing to them?”

Padma tenses. It’s over now, she thinks. Her mother has revealed too much, stepped over the line from charmingly naive to downright insane.

But the pressed-tongue woman seems pleased. “That would be wonderful,” she says. “I’m sure that would make them happy.”

Padma isn’t sure then, but she thinks she sees the currents of her mother’s waters still.

A People's History of Heaven

- Genres: Fiction

- paperback: 320 pages

- Publisher: Algonquin Books

- ISBN-10: 1643750429

- ISBN-13: 9781643750422