Excerpt

Excerpt

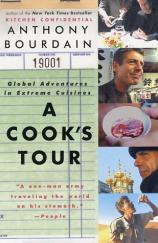

A Cook's Tour: Global Adventures in Extreme Cuisines

Where Food Comes From

'The pig is getting fat. Even as we speak,' said José months later. From the very moment I informed my boss of my plans to eat my way around the world, another living creature's fate was sealed on the other side of the Atlantic. True to his word, José had called his mother in Portugal and told her to start fattening a pig.

I'd heard about this pig business before -- anytime José would hear me waxing poetic about my privileged position as one of the few vendors of old-school hooves and snouts, French charcuterie and offal. Chefs adore this kind of stuff. We like it when we can motivate our customers to try something they might previously have found frightening or repellent. Whether it's a stroke to our egos or a genuine love of that kind of rustic, rural, French brasserie soul food (the real stuff -- not that tricked-out squeezebottle chicanery with the plumage), we love it. It makes us proud and happy to see our customers sucking the marrow out of veal bones, munching on pig's feet, picking over oxtails or beef cheeks. It gives us purpose in life, as if we've done something truly good and laudable that day, brought beauty, hope, enlightenment to our dining rooms and a quiet sort of honor to ourselves and our profession.

'First, We fatten the pig ... for maybe six months. Until he is ready. Then in the winter -- it must be the winter, so it is cold enough -- we kill the pig. Then we cook the heart and the tenderloin for the butchers. Then we eat. We eat everything. We make hams and sausage, stews, casseroles, soup. We use' -- José stressed this -- 'every part.'

'It's kind of a big party,' interjected Armando, the preeminent ball-busting waiter and senior member of our Portuguese contingent at Les Halles.

'You've heard of this?' I asked skeptically. I like Armando -- and he's a great waiter -- but what he says is sometimes at variance with the truth. He likes it when middle-aged ladies from the Midwest come to the restaurant and ask for me, wanting to get their books signed. He sidles over and whispers in confidential tones, 'You know, of course, that the chef is gay? My longtime companion ... a wonderful man. Wonderful.' That's Armando's idea of fun.

'Oh yes!' he said. 'Everyone does it in my town. Maybe once a year. It's a tradition. It goes back to the Middle Ages. Long time.'

'And you eat everything?'

'Everything. The blood. The guts. The ears. Everything. It's delicious.' Armando looked way too happy remembering this. 'Wait! We don't eat everything. The pig's bladder? We blow it up, inflate it, and we make a soccer ball for the children.'

'What's with the soccer ball?' I asked David, also Portuguese, our bar manager and a trusted friend. He shrugged, not wanting to contradict his countryman.

'That's in the north,' he said. 'But I've seen it.'

'You've seen it?'

David nodded and gave me a warning look that said, You don't know what you're in for. 'There's a lot of blood. And the pig makes a lot of noise when you ... you know ... kill it. A lot of noise.'

'You can hear the screams in the next village,' Armando said, grinning.

'Yeah? Well, I'll bring you the bladder, bro,' I said, deciding right then and there that I was going to do this, travel to Portugal and take part in a medieval pig slaughter. Listening to José's description, it sounded kinda cool. A bunch of villagers hanging out, drinking, killing things and eating them. There was no mistaking José's enthusiasm for the event. I was in.

Understand this about me -- and about most chefs, I'm guessing: For my entire professional career, I've been like Michael Corleone in The Godfather, Part II, ordering up death over the phone, or with a nod or a glance. When I want meat, I make a call, or I give my sous-chef, my butcher, or my charcutier a look and they make the call. On the other end of the line, my version of Rocco, Al Neary, or Lucca Brazzi either does the job himself or calls somebody else who gets the thing done. Sooner or later, somewhere -- whether in the Midwest, or upstate New York, or on a farm in rural Pennsylvania, or as far away as Scotland -- something dies. Every time I have picked up the phone or ticked off an item on my order sheet, I have basically caused a living thing to die. What arrives in my kitchen, however, is not the bleeding, still-warm body of my victim, eyes open, giving me an accusatory look that says, 'Why me, Tony? Why me?' I don't have to see that part. The only evidence of my crimes is the relatively antiseptic boxed or plastic-wrapped appearance of what is inarguably meat. I had never, until I arrived on a farm in northern Portugal, had to look my victim in the face -- much less watched at close range -- as he was slaughtered, disemboweled, and broken down into constituent parts. It was only fair, I figured, that I should have to watch as the blade went in. I'd been vocal, to say the least, in my advocacy of meat, animal fat, and offal. I'd said some very unkind things about vegetarians. Let me find out what we're all talking about, I thought. I would learn -- really learn -- where food actually comes from.

It's always a tremendous advantage when visiting another country, especially when you're as uninformed and ill-prepared as I was, to be the guest of a native. You can usually cut right to the good stuff, live close to the ground, experience the place from a perspective as close to local as you're likely to get.

Excerpted from A Cook's Tour © Copyright 2003 by Anthony Bourdain. Reprinted with permission by Ecco, an imprint of HarperCollins. All rights reserved.

A Cook's Tour: Global Adventures in Extreme Cuisines

- paperback: 288 pages

- Publisher: Harper Perennial

- ISBN-10: 0060012781

- ISBN-13: 9780060012786