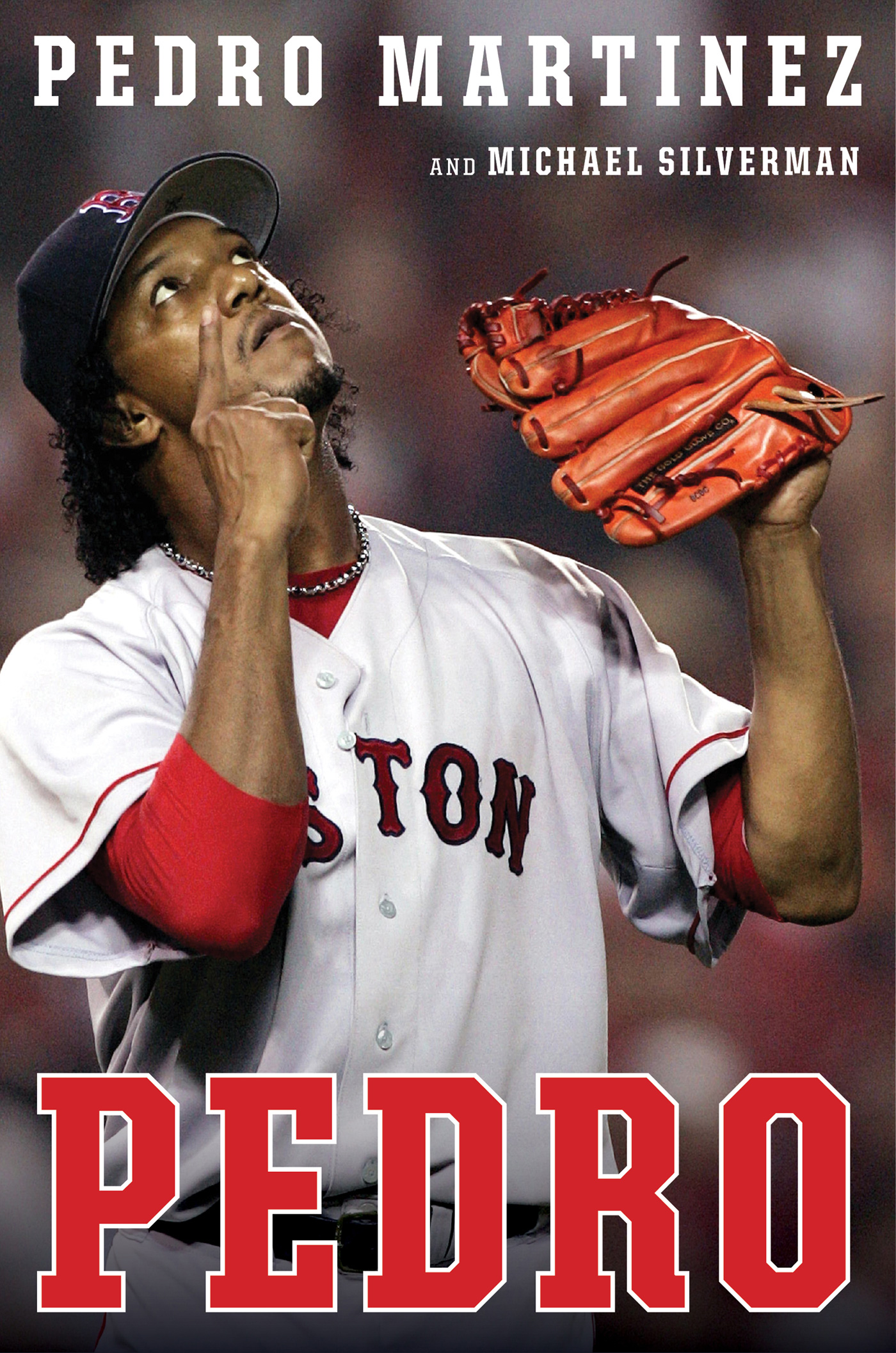

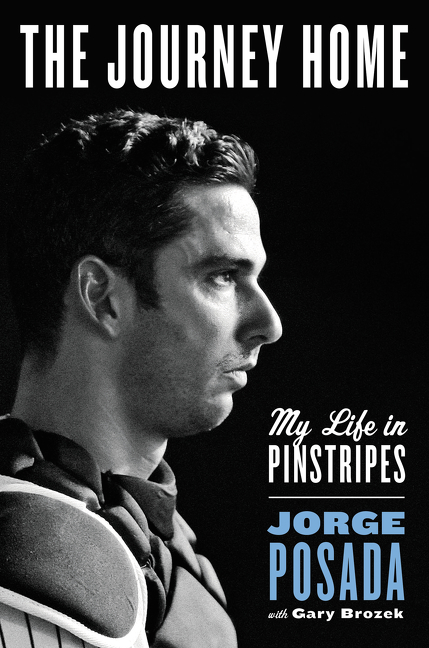

Memoirs from Former Major Leaguers Pedro Martinez and Jorge Posada

Baseball Books

Memoirs from Former Major Leaguers Pedro Martinez and Jorge Posada

There are a number of similarities in the memoirs of Pedro Martinez and Jorge Posada: both were star ballplayers, brought up in Hispanic locales (the Dominican Republic and Puerto Rico, respectively), with strong family ties and adjustment issues when coming to the United States.

The differences are marked, too. One was a pitcher; the other a catcher/everyday player. One has been inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame; the other was a solid player for a frequent world champion team. One comes across as having a tremendous sense of self, a larger-than-life personality; the other, the “normal” amount and much more down to earth. In the end, one retired gracefully, while the other kept trying to hang on.

Martinez, who will be inducted into the Hall this summer, presents a most macho figure, which is obviously very important to him. “Respect” is a word that is used frequently and usually to complain about a discernible lack thereof, whether from the front office/management of his various teams (he played for five in his 18 major league seasons; Posada spent his entire 17-year career with the Bronx Bombers) or opponents standing too close to home plate, which Martinez considers his property and in need of defending. He earned a reputation as a “headhunter,” a pitcher who throws dangerously high and close to a batter with the intent of “sending a message” (and, often, injuring the hitter). Yet he was often surprised that the opponents took umbrage in such circumstances. Obviously, they didn’t understand the nuances of the game, he suggests.

Martinez, who will be inducted into the Hall this summer, presents a most macho figure, which is obviously very important to him. “Respect” is a word that is used frequently and usually to complain about a discernible lack thereof, whether from the front office/management of his various teams (he played for five in his 18 major league seasons; Posada spent his entire 17-year career with the Bronx Bombers) or opponents standing too close to home plate, which Martinez considers his property and in need of defending. He earned a reputation as a “headhunter,” a pitcher who throws dangerously high and close to a batter with the intent of “sending a message” (and, often, injuring the hitter). Yet he was often surprised that the opponents took umbrage in such circumstances. Obviously, they didn’t understand the nuances of the game, he suggests.

Throughout his eponymous memoir (another indication of ego?), Martinez takes the lion’s share of credit for developing into one of the all-time greats; he enjoys making use of numbers to redundantly bolster his stature. And he’s almost always in the right. In some respects, his accomplishments came despite indifference from some of his coaches. Even when he praises his teammates, such as Red Sox catcher Jason Varitek, it comes with a self-congratulatory nod. “I want this kid catching,” Martinez tells his manager at the time, “And you’re going to do what I tell you to do.” Then, “[Varitek] took everything he knew and put it aside to become what I wanted him to become behind the plate.”

Posada, on the other hand, comes across as a much more gentle soul in THE JOURNEY HOME. Yes, he also worked hard to attain his success, but there’s a sense of gratitude there, especially for lasting friendships he developed with Derek Jeter, Mariano Rivera and Andy Pettitte, fellow members of the “Core Four” who came up through the minor leagues together.

Posada, on the other hand, comes across as a much more gentle soul in THE JOURNEY HOME. Yes, he also worked hard to attain his success, but there’s a sense of gratitude there, especially for lasting friendships he developed with Derek Jeter, Mariano Rivera and Andy Pettitte, fellow members of the “Core Four” who came up through the minor leagues together.

Both men wax sentimental when recalling the contributions of their fathers in their development as athletes and as men. The Martinez and Posada paterfamilias were astute local heroes in their own right who tutored their sons with a firm hand; as in many such relationships, approval was tacit rather than open. Posada concludes his story with a touching exchange with his father while throwing out a ceremonial first pitch at Yankee Stadium following his retirement.

Not surprisingly, the rivals have their version of the events that transpired in Game Three of the 2003 American League Championship Series. Martinez --- who historically is the villain for “throwing” Don Zimmer, a 72-year-old Yankee coach, to the ground when the latter charged him following some beanball bravado --- devotes an entire chapter to the incident, claiming, among other things, that Posada cursed his mother, the most disrespectful of all sins in the Hispanic culture. (Space does not permit going into all the details of the controversy).

Posada does not deny these accusations in the three pages he feels sufficient to cover matters. In fact, his comments about Martinez are probably the angriest he offers in his book. (Some local New York media chose to focus excerpts from THE JOURNEY HOME on his last season with the Yankees in which Posada himself felt disrespected, given his long service with the team. But he follows up with what feels like an apology, realizing that baseball is, after all, a business.)

Another issue both authors address in different ways is that of performance-enhancing drugs. The vast majority of current and former players attest they never actually saw anything untoward going on in the locker room; it was all hearsay. Martinez takes an inferential tack, frequently commenting on a player like Roger Clemens, who has been accused of imbibing later in his illustrious career, with “I’m just sayin’” remarks.

Both PEDRO and THE JOURNEY HOME are fairly standard fare. If you’re predisposed to admire or dislike one or the other, I don’t know if either of these books would change your mind.

--- Reviewed by Ron Kaplan