In a speech to the Mills College class of 1983, Ursula K. Le Guin set out to talk “like a woman.” She said, “It’s going to sound terrible” --- because instead of deluging the graduates with golden promises of success, she spoke to them of children, failure and dark places.

In a speech to the Mills College class of 1983, Ursula K. Le Guin set out to talk “like a woman.” She said, “It’s going to sound terrible” --- because instead of deluging the graduates with golden promises of success, she spoke to them of children, failure and dark places.

So I decided, in remembering Le Guin, to “sound terrible,” too: to talk like a woman, despite the warning voices in my head that it’s too personal, too egotistical, not intellectual enough. Panegyrists, those voices assure me, should be world-historical, big-picture, profound. But I’m simply trying to get at what she meant to me.

I’m a woman, I’m old (I no longer say “older”) and I write fantasy --- or try to. My identification with Le Guin, 16 years my senior, has been intense. With her death, I feel that I’ve lost my lodestar: a friend --- never met in the flesh, only on the page --- who wouldn’t let my conscience sleep or my standards wobble.

Fantasy and sci-fi --- from Oz to Asimov, Edgar Rice Burroughs (Mars, not Tarzan) to Tolkien and C.S. Lewis --- have always been my favorite things to read, and when I grew up, I felt guilty about it. Le Guin cured me of that. I was in my 30s when I read most of her most celebrated novels (including the young adult Earthsea trilogy, with its marvelous everyday magic and pre-Rowling school for wizards). Her writing was so astounding, fierce and lyrical, and her vision so compelling, that I never thought I really should be reading Updike or Styron or Roth.

Le Guin wasn’t a snob. She saw no contradiction between the “Amazing Stories”-type pulp fantasy she loved as a kid and literary models like Dickens and Austen and Woolf. After all, those writers also created worlds --- every novelist does --- though theirs stayed on Planet Earth and were sometimes more internal (Woolf) than external (Dickens’ teeming London, Austen’s Hampshire drawing rooms). She always fought for the legitimacy of the genre, furious that speculative fiction was confined to a lesser literary ghetto, while “realistic” writers got most of the prizes, money and media play.

Yet she changed the genre even as she worked within it. Politically, I came of age with the disarmament, civil rights and student/counter-culture movements, and the second wave of feminism. Le Guin anticipated and reflected all these, though from a slightly older vantage point. When she started writing fantasy and sci-fi, most of its writers and protagonists were white men, the source of ideas was usually hard science, and the action often amounted to a battle between heroes and villains.

Yet she changed the genre even as she worked within it. Politically, I came of age with the disarmament, civil rights and student/counter-culture movements, and the second wave of feminism. Le Guin anticipated and reflected all these, though from a slightly older vantage point. When she started writing fantasy and sci-fi, most of its writers and protagonists were white men, the source of ideas was usually hard science, and the action often amounted to a battle between heroes and villains.

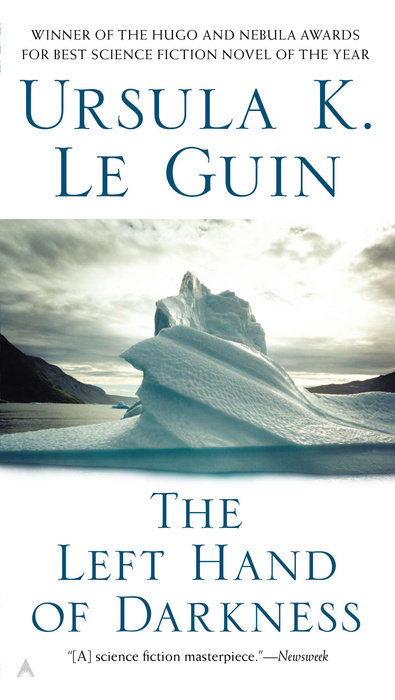

She broke the rules. She was one of the first in her field to think anthropologically --- that is, to see skin color and gender as culturally determined, arbitrarily ascribed more or less value depending on the society. In THE LEFT HAND OF DARKNESS, gender is fluid; people are neither male nor female. In the Earthsea books --- in fact, in most of her work --- white skin is the exception, not the rule. THE DISPOSSESSED imagines how an anarchist society would work, or not; its subtitle is “An Ambiguous Utopia” (my italics).

She was rarely prescriptive. I love Margaret Atwood’s powerful dystopias, but Le Guin’s cultures are different, neither warnings nor blueprints. Her characters aren’t mouthpieces but ordinary flawed people: sometimes generous, sometimes devious, more prone to making mistakes than making war. Her imagined worlds are rich in concrete detail (on the Ice Age planet of LEFT HAND, “winter doors” are set 10 feet above the ground so inhabitants have access during the months of deep snow), yet they also have a dimension of mystery, if not outright magic, and an infallibly human texture. When I reread LEFT HAND a few months ago, what struck me most keenly was the friendship between the narrator, an observer from another planet, and a native lord of indeterminate sexuality whose compassion and courage bridge the cultural divide. It’s a love story of an odd sort.

As I got older, Le Guin got old --- but that seemed only to embolden her. Her 2014 speech at the National Book Awards ceremony, where she received the Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters, went viral. She shared the award with fantasy and sci-fi authors “who were excluded from literature for so long” and then spoke on behalf of all writers, attacking the capitalist publishing industry for selling books “like deodorant.” At 85, she was more anti-establishment than ever.

As I got older, Le Guin got old --- but that seemed only to embolden her. Her 2014 speech at the National Book Awards ceremony, where she received the Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters, went viral. She shared the award with fantasy and sci-fi authors “who were excluded from literature for so long” and then spoke on behalf of all writers, attacking the capitalist publishing industry for selling books “like deodorant.” At 85, she was more anti-establishment than ever.

She had staked out this geriatric radicalism as early as 1974. In a story called “The Day Before the Revolution,” she got inside the head of a woman of 72 (my age now), who in her youth had spearheaded an anarchist movement. This former firebrand has suffered a stroke, and her world has narrowed to a litany of aches and pains, despite the revolution exploding around her. She is impressively honest about the indignities of age and --- most shocking to me at the time --- about the persistence of sexual feelings in a body she now finds “grotesque.”

Then, in an essay two years later, “The Space Crone,” Le Guin suggested that the postmenopausal years are more opportunity than ordeal. Old women, she wrote, need to “become pregnant” with ourselves, embrace the possibilities of age, and realize that we can “do, say, and think” things younger women cannot. That’s freedom. (And Le Guin herself took full advantage of Cronehood, blogging vigorously as late as last September.)

I first read this material 40 years ago, but it lingered. It’s probably what gave me the courage to embark, in my 60s, on a fantasy novel. “[P]eople --- particularly women --- need to hear that you can start late,” said Le Guin in a 2013 Paris Review interview, speaking of her own mother, who began writing in her 50s. I think --- I hope --- she would tell me to persist.