Interview: March 29, 2013

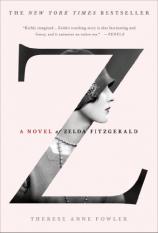

Therese Anne Fowler’s highly-anticipated novel, Z, details the romantic, tumultuous and extraordinary marriage of Zelda Sayre and one of the 20th-century’s greatest American writers, F. Scott Fitzgerald. In this interview, conducted by Bookreporter.com’s Bronwyn Miller, Fowler discusses her inspiration for the book and her extensive research, which involved studying newspaper clippings, photographs, book reviews, Zelda’s artwork, even ticket stubs. She also addresses Zelda’s mental health, explains the nod to Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s HERLAND in the story, and talks about the benefits and drawbacks of competition, which plays a big part in the novel.

Bookreporter.com: What inspired you to write a novel about Zelda Fitzgerald?

Therese Anne Fowler: The idea to write Zelda’s story struck without warning on a day when I was assessing other entirely unrelated, non-biographical story ideas. I’d been writing about them in my journal, then had this “Oh! What about Zelda Fitzgerald?” thought that stopped me in my tracks. It was the strangest thing.

Stranger still was what I found when I went to my computer to look up this person who I knew only as “F. Scott Fitzgerald’s crazy, disruptive wife”: she and my mother had both passed away in the overnight hours on the same date, March 10th --- though in different years, obviously.

The coincidence was eerie, especially given how I’d come to have the idea in the first place. But even as I was intrigued, I was also skeptical --- this wasn’t my usual approach to deciding which of my ideas merited the investment of the next year of my life. What’s more, writing fiction about real people is a dicey business. And writing about a woman who, at that stage, seemed a bit…unsympathetic, well, it just felt like a bad idea. But I dug a little deeper and got a glimpse of a very different woman than I expected. The more I learned, the more compelled I was to learn more, until there was no longer any question that I would attempt to write a novel about her.

BRC: There are about as many theories on what makes a successful marriage as there are marriages. A memorable one that has been espoused by some is called the “flower/gardener” theory: in order for a marriage to work, one person is the flower, the one to be nurtured and cared for, and the other must be the gardener, the one who does the caretaking. Do you think Scott and Zelda’s marriage would fall into this category? Do you think that two passionate, creative types can coexist in a marriage successfully, or does the flower/gardener theory apply?

TAF: As lovely and right as the “flower/gardener” theory sounds, I’m certain that we all could name happy couples who are passionate, creative flower/flower types. Paul Newman and Joanne Woodward come to mind, and there are many others.

In Scott and Zelda’s case, there were so many outside influences and complicating factors --- not the least of which is how young they were at the outset of their fame --- that we could spend a whole day discussing what went right, what went wrong, and why.

BRC: Hemingway has a terrific line when describing to Zelda what challenges her husband will face as a writer: “A writer’s life is a difficult one. He should accept this and embrace it fully. No greatness is possible without failure and sacrifice.” Was this last line an actual quote from Hemingway or one from you? Do you believe this to be true? If so, what failures and sacrifices have you made for your career?

TAF: This is not an actual quote, but it’s drawn from Hemingway’s established views on the writing life. I do think the statement is generally true for most if not all writers, especially those of us who write fiction or poetry.

My “failures” (a term I use advisedly because everything has value of some kind), run from things as mundane as bad writing days that result in more backward progress than forward, to the years I spent struggling to learn the craft and write my first (unpublished, not-very-good) novel only to be widely rejected by agents, to the disappointing sales of my third novel.

Sacrifices for me are mainly things like financial/job security and the possibility of working regularly in a stimulating social environment --- both of which I would enjoy greatly.

The writer’s life is difficult because rejection and criticism are omnipresent, never-ending themes --- and are heightened, now, by the prevalence of electronic and social media. Grace, stubbornness, determination: these are traits professional writers have to strive for, and if they can’t achieve them, they’re far better off pursuing a gentler occupation.

BRC: So much is made of Zelda being a “distraction” to Scott’s work, as Hemingway unsubtly states: “A woman who knows how not to be a distraction to her husband’s career is a good and fine and honorable woman.” Do you think Zelda was ever a distraction to her husband, or was she just a convenient excuse?

TAF: Yes, she was a distraction at times, though I think rarely deliberately so. More to the point was Scott’s growing inability to focus on his work due to insecurity and alcohol abuse. Often, he manufactured distractions; Zelda reacted to them and Hemingway reacted to that.

BRC: Competition plays a big part in the novel. There’s competition between Hemingway and Fitzgerald, Zelda and Scott, and even Zelda and Hemingway. When is competition a good, healthy thing, and when is it harmful? Can competition make you a better writer, or is it better to “keep your eyes on your own paper”?

TAF: Healthy competition makes better writers, there’s no question about it. In a thriving writing community, writers learn from one another. Ambitious writers study their predecessors and their successful cohorts in order to improve their own efforts. They recognize that there is always room for another good story or good book.

Competitiveness becomes problematic when too much ego causes a writer to believe he or she can only succeed if other writers fail.

BRC: Part IV begins with a George Eliot quote: “No evil dooms us hopelessly except the evil we love, and desire to continue in, and make no effort to escape from.” This line succinctly describes Scott’s problems. But does it also apply to Zelda?

TAF: It does, in part. What Zelda eventually gained that Scott was lacking was a clearer perspective on the matter.

BRC: At one point in the story, an editor and several other friends of the couple comment on the nature of the friendship between Scott and Hemingway. Do you believe there was a sexual relationship there, or was it just the kind of male bonding that today would be called a “bromance”?

TAF: It’s nearly impossible to know the truth about anyone’s intimate life --- even people we know well and see regularly --- unless they reveal that truth personally. My position on the matter aligns with Zelda’s in the novel.

BRC: After having it out with Scott over Ernest, Zelda realizes that she’s been displaced in Scott’s affections: “That was the thing with Scott. If he loved you truly, he had trouble seeing your flaws. What a gift, I thought. What a curse.” Even though she stayed with her husband, do you think this moment was the tipping point for her?

TAF: It weights the scale heavily, for sure.

BRC: While in the Swiss hospital, after being diagnosed with schizophrenia, and many sessions with doctors focusing on her “failures,” Zelda realizes what they and Scott have been trying to impress upon her: “So there it was, in plain English: my main failure, the reason for all our trouble, was that I hadn’t created a secure hearth, a tether for my husband. I wondered if it was possible to tether Scott, but kept that thought to myself.” For someone who supposedly had mental issues, she seemed to have a grasp of the irony of her situation. Do you think this was Scott’s main issue with their marriage, or just the mindset of the time?

TAF: I like that you say “supposedly” had “mental issues,” because what she had at that time were primarily complications from anorexia and exhaustion and marital stress. As soon as she was rested, her clarity was restored.

Scott was greatly influenced by Zelda’s doctors and the prevailing medical beliefs of the time. If the top experts said a thing, he felt there must be something to it.

BRC: Zelda and Scott’s daughter, Scottie, chose these lines from THE GREAT GATSBY for her parents’ epitaph: “So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.” Why do you think she chose this particular line?

TAF: I have my view of course, but I’d rather leave the question for readers to ponder.

BRC: At the time, Zelda was diagnosed as a schizophrenic. Today, she would more likely be labeled as bipolar. Do you think her subjugation of her husband added to or caused her problems? If she and Scott had lived today as a married couple, do you think they would have fared any better?

TAF: It’s important to note that Zelda’s illness didn’t manifest until she was almost 30 years old, triggered by the factors I mentioned above. Popular culture looks at some of her more audacious youthful behavior and frames it --- and her --- as “crazy,” ignoring the timeline and latching onto that schizophrenia tag.

She was likely bipolar, and as most of us know or should know, having bipolar disorder doesn’t necessarily lead to audacious behavior. Zelda was simply high-spirited and uninhibited. Today, she would be very much the same, but would have the ability to treat her depression effectively. The treatment she was given in the '30s caused, over time, more difficulties than it resolved. So yes, I believe they would fare better today.

BRC: How did you research this book? Do you feel a certain responsibility when writing about a real person as opposed to a fictional character? How is it different from writing a fictional character?

TAF: The Fitzgeralds were great chroniclers of their own lives, so I was able to study all kinds of paraphernalia: newspaper clippings, photos, ticket stubs, recital and play programs dating into their childhoods; most of Zelda’s letters to Scott and some of his to her; Scott’s ledgers (which date back to his childhood); newspaper clippings about them from their early celebrity years; book reviews; photographs; souvenirs such as passports and ticket stubs; and Zelda’s artwork --- which continues to be exhibited periodically and is remarkable.

I read collections of letters exchanged between Scott and Hemingway, Scott and other friends, Scott and his agent and editor --- as well as some letters Scott’s friends wrote to one another talking about the Fitzgeralds. Also useful were the essays they each wrote and published, which detail (with some embellishments, at times) some of their views and experiences, and their short stories and novels, which present a wealth of autobiographical material within the fictions.

My personal approach to writing fiction about real people is that it’s both unfair and wrong to knowingly mischaracterize their lives --- which mean that even when the truth is inconvenient to story-building; it needs to be respected and accommodated.

With standard fiction, writers build the story and the characters simultaneously and in whatever ways suit their purposes, so the process is entirely different.

BRC: Upon her first meeting with Scott at the Montgomery Country Club, the couple discusses literature. Zelda mentions HERLAND by Charlotte Perkins Gilman. Her own chaotic life reminds me of another Perkins Gilman work “The Yellow Wallpaper,” about a woman who is driven to madness after being shut away by her husband, supposedly for her health. Was the nod to Perkins Gilman intentional?

TAF: I first read the eye-opening story “The Yellow Wallpaper” as a graduate teaching assistant for Dr. Leila May and her popular Studies in Fiction course. It made a great impression on me at the time, and I felt it resonating as I learned Zelda’s story. And so although I didn’t set out to reference Perkins Gilman in the book, when I came to that part of the narrative, the fit felt natural and appropriate.

BRC: I understand that another one of your passions, besides writing, is baseball. You were one of the first girls to play Little League baseball in the U.S. Can you tell us a little bit about that experience? Do you still play?

TAF: Because I was a tomboy, loved baseball, and was somewhat headstrong (not unlike Zelda as a girl), I felt as though I belonged in Little League --- whether the coaches liked it or not. The boys, many of whom were my friends already, accepted me without trouble. If there was any difficulty at all, it was in having to prove to the coaches that I was at least as good as most of the boys --- and better than many of them --- so sticking me in right field automatically (where no one ever hit the ball) wasn’t really warranted.

I don’t play ball now (and it seems that adult rec. leagues are always softball), but I did play throughout my twenties until parenthood took over my free time.

BRC: Can you share what you are working on now?

TAF: I’m contemplating a couple of different ideas, but haven’t settled on one yet.