Interview: June 2, 2006

June 2, 2006

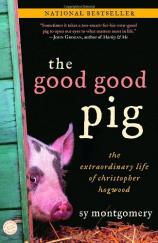

Naturalist, documentary scriptwriter and radio commentator Sy Montgomery has authored award-winning books such as JOURNEY OF THE PINK DOLPHINS, SPELL OF THE TIGER and SEARCH FOR THE GOLDEN MOON BEAR. Her latest work, THE GOOD GOOD PIG, centers on a beloved pig named Christopher Hogwood, who won the hearts of an entire community. Bookreporter.com's contributing writer Shannon McKenna interviewed Montgomery about the exceptional characteristics Christopher possessed and just how much of an impact he had on herself and others throughout the course of his life. She also describes the difficulties of writing about her experiences abroad, her kinship with animals and their significance in the greater scheme of things.

Bookreporter.com: What made you decide to share the story of Christopher Hogwood with readers?

Sy Montgomery: For many years, as I thrashed through jungles to write books about pink dolphins in the Amazon and man-eating tigers in India and golden moon bears in Southeast Asia, people told me I had a great animal story in our own barn. They were right. I finally saw this plainly a short time after Christopher died. His death was headline news not only in the local weekly, but the capitol's daily. We got so many sympathy flowers from his friends that I filled every vase and then every pickle jar in the house. Cards, food, emails, and phone calls flooded in from people who had loved him all over the world. I had always known he was a good, good pig --- but what I hadn't realized was how deeply he had touched so many others, and that if I wrote this book, his spirit could continue to do so.

BRC: Was writing THE GOOD GOOD PIG a difficult experience, a cathartic one, or a bit of both? Ultimately, did you find it uplifting to revisit your memories of life with Chris?

SM: Friends hoped that writing this book would help ease my grief, but it didn't --- at least not while I was writing it. Every chapter felt like a list of all I had lost: the soft fur in back of his ears; the soul-stirring sound of his grunts; pig spa with neighborhood children; the great spectacle of watching him eat. And just a few months after Christopher died, Tess --- our border collie --- died too, at age 16. At the time, writing the book was the only thing that could have made me feel worse than I already did, because I could not escape the loss in my work. But that was OK. I don't write to make myself happy --- I write to create a book, to set down what I think is true and important. And now that I have this testament to Christopher's life between the book's beautiful covers, I am very happy indeed.

BRC: "That spring, it seemed I woke every day to sorrow, as every day carried me closer to my father's death," you write in THE GOOD GOOD PIG. Faced with your father's terminal illness, what made you take in an animal that was sickly and had a slim chance of survival --- an act that could easily have led to more heartbreak?

SM: When you love someone like I loved my father --- and I think we all know this feeling --- you believe somewhere in your heart that this fierce, bottomless love is a force so strong that it SHOULD be able to help you do almost anything. I couldn't save my father, but at least all that love wasn't useless. It could, at least, be applied to help save a sick baby pig!

BRC: You weave historical and scientific facts about pigs throughout the narrative. In addition to painting a colorful portrait of Chris, was it important to you to give readers a greater understanding of pigs in general?

SM: Oh, yes! Chris was surely a pearl among swine, but ALL pigs share with him the talents of their species. Among them: a great emotional range and sensitivity; excellent memory and problem-solving abilities; and a deep appreciation for comfort, affection and food. But most of us seldom think of this when we think of pigs. Otherwise we wouldn't cause millions of these highly intelligent and sensitive souls to suffer on hideous factory farms just so we can eat cheap bacon. With this book about Christopher, I am reminded of the wonderful obituary that Jane Goodall wrote about one of the first chimps she came to know, Flo, an animal who contributed so much to the scientific understanding of her species. "It is true," Jane wrote, "that her life was worthwhile because it enriched human understanding. But even if no one had studied the chimpanzees at Gombe, Flo's life, rich and full of vigor and love, would still have had a meaning and a significance in the pattern of things."

Most pigs will never have a book written about them --- but their lives still have meaning and significance. Or they could, if we weren't so eager to grind them into sausage.

BRC: You've chosen to make it your life's work to write about animals and nature. "Animals have always been my refuge, my avatars, my spirit twins," you confide in THE GOOD GOOD PIG. What do you suppose accounts for your affinity for and kinship with animals? How has the study of animals enriched your life? What can humans learn from animals?

SM: Animals help me feel at home in the world. After all, humans are just one of many millions of species. Think of how impoverished life would be if you only listened to one kind of music, ate only one kind of food, read only one literary genre? That's how I feel about people whose interests are confined to only one species --- their own. They are missing a great deal of what life on this earth has to offer us. For most of human existence, though, most people cared deeply about the rest of the animate world. If you didn't, you couldn't find food --- or a Smilodon came to eat you when you weren't paying attention. For all but the last few moments (evolutionarily speaking) of human existence on earth, everyone knew that animals, like people, are endowed with souls, and animals were eagerly watched, imitated, sought and consulted. I never unlearned this truth.

BRC: You've traveled around the world, visiting and living in some of the most exotic corners of the globe, and yet you write in THE GOOD GOOD PIG that you need "the anchoring fulfillment of home." Why is it essential, perhaps even vital, that you have that anchor in your New Hampshire homestead?

SM: Many people think that the difficult part of my work is the travel --- the sunburn and the chiggers, the tarantulas that crawl into your bed and the piranhas swimming in the water. But no --- that's the part I love!

The hard part happens when I come back and start writing. Given the splendid gift of the opportunity to make these expeditions, what a terrible thing to face the prospect that I could fail to do them justice! That is my deepest fear. And I face it, as all authors do, every time I try to write.

That is one reason why I need this place of peace and welcome to come home to --- a place from which I can feel centered and safe enough to try to make sense of the transformational experience of travel. And then here's the other thing: without a home to return to, I might well disappear into some jungle and never come back.

BRC: Chris made quite an impact on your neighbors and fellow townspeople, with the minister's wife, Maggie --- even keeping a picture of Chris in the parsonage kitchen. What was it about Chris that made him such a vital part of the community, and later quite the celebrity?

SM: I thought about this question deeply and wrote about it in the book. He was adorable as a baby; then people loved him because he was so huge. People loved to bring him slops: it appealed to everyone's Yankee sense of thrift. And then there was the glorious show of watching him eat. People loved him because he was so happy. People loved him because he was so greedy. People loved him because he was so porcine --- and people loved him because he was so human. People loved him for his gentleness and humor. But there was something else as well. The fact that a runt piglet almost too small to live not only survived but grew to adore old age showed that we don't always have to accept the "rules" that society or species, family or fate seems to have written for us. We can choose a new way --- a more compassionate, joyous, loving way. Christopher's life was proof of that.

BRC: Some of the traits that made Christopher unique --- his politeness with wheelchair-bound visitors and gentle manner with shy children being two of them --- are almost human-like. Do you believe they were innate or learned?

SM: I credit both. Most animals are born excellent observers. They watch us so closely that the famous horse Clever Hans was able to guess the correct answers to mathematical problems simply by watching his owner --- who didn't even realize he was giving away the answers by subtle physical cues.

And as Henry Beston wrote in one of my favorite books, THE OUTERMOST HOUSE, "animals are gifted with extensions of the senses we have lost or never attained": pigs have extraordinary hearing and an exquisite sense of smell.

Also, pigs are extremely emotional creatures, and it makes sense that they should be sensitive to the emotional states of others. From what he could see, hear and smell, I think that Christopher understood easily that shy children and people in wheelchairs required special care. It's no wonder he intentionally adjusted his behavior accordingly. He was always rewarded handsomely for his graciousness: he loved nothing more than the adoring caresses and delicious slops that issued from his visitors, whether they were outgoing or shy, disabled or able-bodied. He was an equal opportunity eater.

BRC: Why do you think books like the recent MARLEY AND ME, THE LADY AND THE PANDA, and now THE GOOD GOOD PIG --- all of which explore the relationship between animals and humans --- resonate so strongly with readers?

SM: We live in an era drenched in chemicals, asphalt, cars, malls, steel, electronics. All fine inventions, all great in their place. But the danger is that many of us might forget about the REAL world: the green, living, breathing world full of billions of species besides our own. We are in danger of forgetting that we aren't alone on this spinning blue planet. And if we do so, we lose the world. We lose our humanity. We lose our home.

As we poison our planet, one in every two American men and one in every three women gets cancer. We raze forests and fill wetlands and make our landscape hideous with ugly buildings and strip malls --- then spend a huge portion of our incomes in a desperate search to find some unspoiled place to buy us two weeks of peace every year. We're aware something is wrong. Never before has there been such a proliferation of self-help books and twelve-step programs to help us feel less lost, less frightened, less miserable.

We hunger for connection with the rest of animate creation. That's one reason why I think books about relationships between animals and people resonate so strongly. Relationships with animals remind us that the world is larger and more glorious than our built boxes would suggest, that love is large enough to cross species, and that with compassion, we can learn to heal our crowded, poisoned planet. The animals can lead us home.

BRC: What has been the most memorable comment you've heard thus far from a reader about THE GOOD GOOD PIG?

SM: The folks at Random House/Ballantine had this great idea: they gave Hogwood his own website, goodgoodpig.com. Before the book was even published, librarians and booksellers who were able to obtain advance copies were invited to post their comments on the book. It was great fun reading their views. Everyone loved Hogwood as a character, and some found him as memorable as E. B. White's Wilbur in the classic CHARLOTTE'S WEB.

What a compliment! School librarians in particular were grateful for the message to kids that animals matter (which kids already know; it's just good to have an adult book reaffirm this.) One of the best comments was a promise, and proof that Chris had worked his magic as ambassador for pigs everywhere, and it was this: "No pork on my fork!"

My in-laws' rabbi would heartily support that idea, too.

BRC: What would you most like readers to know about Christopher Hogwood?

SM: When he was alive, the most important thing to know about Christopher was that he didn't like to eat citrus or onions --- and we didn't feed him meat. (Among our reasons: We didn't want him to realize he could eat us.) But for the folks who can now meet him only on the page, what I want them to know is what our friend Lilla Cabot told us shortly after his death. No one could put it better than she: He was, she said, "a big Buddha master for us. He taught us how to love. How to love what life gives you --- to love your slops. What a soul!" she said. "He was a being of pure love."

BRC: What are you working on now, and when can readers expect to see it?

SM: The next book of mine to hit the stores is a nonfiction book for kids titled SEARCH FOR THE TREE KANGAROO coming in October from Houghton Mifflin, for kids grades 4-8. It's the chronicle of an expedition to the cloud forest of New Guinea to study a little-known species with an extraordinary team of people from four countries, with amazing photos by Nic Bishop. It was the most physically strenuous expedition I have ever undertaken --- we had to hike for three days at 10,000 feet, and on one of those days I thought I was having a heart attack for nine hours. But it was also the most healing trip I have ever experienced. Our expedition leader, Dr. Lisa Dabek, named the first pair of tree kangaroos we collared after my beloved lost companions --- Tess and Christopher. I love to think that Tess and Chris are both out there now, in a forest draped with soft moss and flowering orchids bathed in clouds --- a place as close to heaven as I could imagine on this Earth.