Author Talk: August 3, 2017

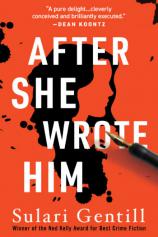

Sulari Gentill is the author of the award-winning Rowland Sinclair Mysteries, a series of historical crime fiction novels set in the 1930s about Rowland Sinclair, the gentleman artist-cum-amateur-detective. Her latest book is CROSSING THE LINES, a postmodern novel that introduces readers to Madeleine, a successful author of a mystery series who decides to write a stand-alone novel about a literary writer named Edward. In this interview, Gentill talks about her longtime fascination with the reciprocal relationship between author and protagonist, and how that influenced her in the writing of this unique novel. She also admits to still being undecided as to which of her protagonists is real and which is imagined, describes herself as a “pantser” (she writes by the seat of her pants), and explains the odd connection between CROSSING THE LINES and her Rowland Sinclair period mysteries.

Question: The protagonist in CROSSING THE LINES, Madeleine, is a successful author of a mystery series set in her native Australia who feels the yen to write a stand-alone novel about a mystery writer named Edward. And here you are, the author of a popular mystery series called the Rowland Sinclair Mysteries, and you have just written a stand-alone novel about a mystery writer. Is this a case of Art imitating Life imitating Art...or what?

Sulari Gentill: I have for some time been intrigued by the reciprocal relationship between author and protagonist. Being the writer of a long-running series (the Rowland Sinclair Mysteries), I’ve had the opportunity to, over several books, really look at that relationship through my own experience. What I’ve discovered is that as much as Rowland Sinclair is a reflection of my values and ideas, I have also been influenced by his, and by the way in which he sees his world. I suppose that’s not surprising. Over eight books I spent a significant part of the last seven years thinking about him.

Madeleine, one of the two protagonists in CROSSING THE LINES, is a successful author of a mystery series set in her native Australia, who decides to write a stand-alone novel about a literary writer named Edward. Whilst her circumstances sound familiar, Madeleine is not me, and CROSSING THE LINES is a novel, not a memoir. In writing this book, I wanted to concentrate on Madeleine’s inner world, and so I gave her an outer world that I knew --- one that’s very similar to my own, a familiar baseline from which I could extrapolate. It’s not something I’ve ever done before, but for this book, which is all about crossing those lines between reality and imagination, it was right. Perhaps it’s Art imitating Life, perhaps it’s Art and Life merging somehow, or perhaps we’re all part of somebody else’s story.

Q: The unreliable narrator is a much-beloved literary tradition. Were there any particular antecedents in either mystery fiction or literary fiction that influence you in the writing of CROSSING THE LINES?

SG: Rather than being influenced by characters or books in the writing of CROSSING THE LINES, I think I was influenced by writers themselves --- those late-night confessions when writers gather to talk as colleagues. So many of us seem to have developed real relationships with the people in our heads, we talk to our characters, and feel the presence of the people we conjure in our books in our day-to-day lives. I suppose being a writer often involves working on the edge of the line between imagination and delusion. Perhaps in order to make our characters real to readers, we must allow them to become real to ourselves, to some extent at least. I know writers who wouldn’t stop writing at a particular point in the manuscript lest something happened to them and their protagonist was stranded forever in peril and despair. I know writers who fell out of love because their partner didn’t measure up to the hero they’d made up. I know writers who have felt enormous guilt for what they put their protagonist through.

It was all these peculiarly writerly things that influenced me in creating Madeleine and Edward, whose unreliability as narrators is the essence of the story. Each allows their personal feelings about the other to influence the narrative. Writers often talk about characters behaving unexpectedly, taking the plot in a direction that they hadn’t anticipated. This is what happens in CROSSING THE LINES, though the plotlines with which Madeleine and Edward interfere are each other’s and not their own.

Q: Although both Madeleine and her fictional creation Edward are mystery writers, would you call CROSSING THE LINES a mystery? If not, then what?

SG: I’m not sure that Edward is necessarily Madeleine’s fictional creation. She could just as easily be his. In fact, CROSSING THE LINES opens from his point of view. Edward is a literary writer. He intends to insert a mystery writer into a serious novel about the meaning of life, just as Madeleine intends to insert a serious writer into a crime fiction. CROSSING THE LINES is, I think, a mystery --- or a mystery within a mystery…but not just that. The narrative takes you into the mind of the writer as well as the protagonist, allowing you to see the mechanics of storytelling as part of the end product. It’s a little like a skeleton clock, I suppose. You can see all the gears and cogs of this novel, but that does not detract from the fact that it works. There’s still a body, numerous people with motives, investigations, love interests, betrayal, secrets and conflict. There’s even a car chase. But that’s just one facet of a multifaceted narrative. It’s also the story of telling a story.

Q: The pre-pub reviews for CROSSING THE LINES have been excellent thus far, but in my own case, I am not certain that I read the book in the same manner as those reviewers. Without giving away any spoilers, do you feel there is any ambiguity to what constitutes "reality" as it is presented in the book? Or do you feel the plot develops in a straight line?

SG: Although I wrote CROSSING THE LINES, I admit I’m still undecided as to which of the protagonists is real and which is imagined. Some days I’m sure it’s Madeleine’s story, other days it feels like something Edward cooked up. Reality in this book is ambiguous, and that ambiguity is an essential part of the story. Who is real? Who is imagined? Does it change? Does it matter? I want readers to decide those questions for themselves. I didn’t ever want this book to be a puzzle with just one solution; that’s not in my experience how either imagination or life works. This plot is more spiral than straight. It turns in on itself, circling towards a core in which the protagonists leave the outside world behind and come together in a reality of their own creation.

Q: When you conceived of CROSSING THE LINES, did the story develop exactly as it turns out in the book's finished form? Or did your two principal characters surprise you along the way?

SG: CROSSING THE LINES was never really conceived in any complete form. I don’t generally plot any of my novels. I am what we call in Australia a pantser (someone who writes by the seat of their pants). I just sit down and write, allowing the story to unfold as it will. So, too, was it with CROSSING THE LINES. I began with the idea that heads the first chapter: What if you were writing of someone who was writing of you? In the end, which of you would be real? That notion, that question, was all I had. I didn’t have a plot or an answer. I saw Madeleine through Edward’s eyes first and then allowed her to define him, partly by the way he saw her. And everything happened very organically from there. Did the characters surprise me? Yes and no. Yes, because I didn’t have any idea what they would do next. No, because I had no expectation of what they would do next.

Q: This novel is quite a departure from your Rowland Sinclair period mysteries. How do you think it will be received? And do you anticipate the majority of the readers being a group apart from the Rowland Sinclair fans?

SG: I try not to think too much of how any of my books will be received. Therein lies madness, or at least a stomach ulcer! For an author releasing a book is a little like sending your children to school for the first time. You desperately hope they’ll find their place in the world, that they’ll make friends, that people will be kind to them and love them as you, but you have very little control over whether that happens. All you can really do is hope. That said, although CROSSING THE LINES is a departure from my previous work, it is connected in an odd way. This is not a book I could have written had I not written eight Rowland Sinclair Mysteries first; if I had not come to understand the intense, reciprocal relationship that exists between writer and protagonist; if I had not been able to observe my own reactions over the years to the man I made up. You could say the research for writing this book included writing all the books I have before, and the mystery at its core is that of the writer’s mind.

I’ve noticed that of all the questions I am asked at literary festivals, readings, etc., the most popular concern my writing process and my relationship with Rowland Sinclair: Where did he come from? Is he based on anyone? Does he talk to me? What would he think of current events? Why do I nearly kill him in every book? Who would I like to play him in the movie? I’ve found myself speaking often about “the line” between imagination and delusion, confessing to those times I’ve ventured a toe across it. This book deals with those same questions. So whilst CROSSING THE LINES is not a traditional mystery, I do still hope its readers will include the fans of Rowland Sinclair.