Author Talk: May 8, 2009

AUTHOR TALK

May 8, 2009

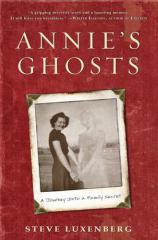

Steve Luxenberg, an associate editor at The Washington Post, recently published his first book, ANNIE'S GHOSTS, which chronicles his search to uncover a family secret kept hidden for over half a century. In this interview conducted by author Laura Wexler (FIRE IN A CANEBRAKE: The Last Mass Lynching in America), Luxenberg discusses the two roles he plays in the narrative --- one as a journalist, and the other as the son of one of his subjects --- and the importance of incorporating both equally in order to fully tell the story. He also describes the challenges of writing the book in a style that combines three different genres, recalls his experience visiting a European city that significantly impacted his family's history, and shares the discovery that brought him comfort in spite of the tragic events he was able to bring to light.

Question: You say several times in ANNIE'S GHOSTS that you were working to balance your roles as a reporter and as a son. Can you discuss how you navigated these roles, and describe any situations that challenged the balance you created?

Steve Luxenberg: The secret first emerged during a time when my mom was quite sick, and my siblings and I were trying to figure out how to deal with her frequent trips to the hospital emergency room and her resulting anxiety. That initially put me in the role of son, and as a son, I believed what Mom had told her doctor and what was reported to us: That she had no idea what had happened to her sister. Of course, that turned out not to be true.

Once I set out to write the book, I wanted to tell the story fully, without holding back. I’ve been a journalist for so long that it wasn’t hard for me to slip into the role of questioner and observer. I sometimes wonder if that’s one reason why I chose journalism. It’s one of the few professions that sometimes demands immersion in difficult and emotional subjects, while allowing the reporter to set aside, or even submerge, his or her own feelings.

A book puts the writer into a more complex relationship with the material. I wanted to apply the discipline of journalism to ferret out the story, but I didn’t want to push aside my feelings --- they were part of the story, too. Sometimes I found myself taking notes on my own reactions, and that felt strange at first.

Q: At some points in the narrative, I see you holding back your personal reaction to avoid influencing the person you’re interviewing. Can you talk about that?

SL: The most difficult moment came when my cousin, Anna Oliwek, replayed her long-ago argument with my mom over the secret. This argument was in the early 1950s, not long after Anna emigrated to the United States and learned from older family members about Annie.

To put it bluntly, Anna had nothing but contempt for Mom’s decision to hide Annie’s existence. I didn’t want to defend Mom, but later I realized that as the reporter, as the storyteller, I had to push back if I wanted to go deeper into understanding Anna’s feelings and my mother’s motivations. As a writer, that was liberating. But it was also somewhat liberating as a son.

Q: Along the same lines, your book is a hybrid of memoir, a genre that embraces subjectivity (some say to an extreme degree), and journalism and history (which ostensibly rely on objectivity). What challenges resulted from working in these three different genres? After so many years in journalism, was it difficult to write personally, with yourself as the main character?

SL: Honestly, it was more fun than difficult. Sure, there were challenges, but they were the challenges that came from trying to untangle a complicated and hidden story, not from writing in a personal voice.

When my book proposal went out to publishers, one interested editor wondered whether the story might be better told as straight history/biography, keeping myself out of it. Generally, I prefer that style, but it demands authoritativeness, and I wasn’t sure I could gather enough information to achieve that voice. I saw ANNIE'S GHOSTS as a story about a search, about putting myself in someone else’s place, about whether the truth can be found, and how to navigate the distortions that memory imposes on the truth. It seemed natural to write the story as part memoir and part history, while separating my memories from those of the people I found and interviewed.

The book doesn’t fit neatly into any one genre, I’ve been told. That pleases me. It sounds rather appealing to be operating in the cracks between various styles. No writer minds being accused of doing something different.

One early online reviewer wrote: “It’s a true story that reads like a true story.” I loved that. Some memoirists have given the genre a shaky reputation by employing invented dialogue or scenes. They defend those techniques as a way to reflect the essence of what really happened. It seems to me that writers already have a genre for that approach. It’s called the novel.

Q: You put sections of personal memory into italics, as if you’re consciously trying to prevent the memoir thread from infiltrating the journalistic thread. Can you discuss the various levels and kinds of narrative at work here?

SL: A writer doesn’t want to give away too many secrets! But yes, I wanted to set off the sections, to flag those as my voice, and my voice alone --- and to warn readers that these vignettes come largely from memory, not from research.

Those sections, which appear throughout the book, stand as a running (and somewhat separate) narrative of my attempts to reconcile the mom I remembered and the secret keeper that I had discovered. These sections also support the theme of reinterpretation: They exist as memories, but must I now reinterpret all my memories in light of the information I’m uncovering?

Q: As you got deeper in your research, what was the biggest surprise you encountered?

SL: I never thought I’d find so many secrets, with so many levels and implications --- and not just in my own family. In retrospect, I’m not sure why I wasn’t prepared for that. I suppose it seems obvious that secrets beget other secrets. Chalk it up to naivety.

The difficulty of getting Annie’s records also was a surprise. I had no idea that a family member would have such trouble seeking information about someone long dead. I think we need to revisit our privacy laws, and make sure that they don’t prevent us from telling our own history.

Q: Did you worry that you wouldn’t be able to learn enough about Annie’s life to write the book?

SL: In a word, yes. Like any writer, I wanted to work with the complete record of her institutionalization, to spend hours interviewing a doctor who had treated her or find an attendant who had worked on her ward. The book isn’t the story of her life, though. It’s the story of a secret and its consequences, and how that secret remained powerful. Recreating Annie’s world was crucial to telling that story, but recreating Annie’s life was not. The book has several narratives in play; removing Annie’s anonymity is one of them.

Q: You found a lot of secrets in the course of your research. Do you think your family had more secrets than the “average family”?

SL: In the book, I wrote that I’ve become a collector of other families’ secrets. It’s remarkable how many families have something hidden, a subject that everyone “knows” is not to be discussed. Every generation seems to create its own taboos, although some old ones linger on.

Today, of course, revealing family secrets has become fashionable, even a staple of TV talk shows. I interviewed Deborah Cohen, a professor at Brown, who is writing a book about the rise of the “confessional culture” in Britain. We had a fascinating discussion about my dual role as son and journalist, which I relate in the book.

Q: At least one of your siblings had been a bit hesitant about your quest. Do they still feel that way, now that the book is done? How do you think your family was affected by the information you uncovered?

SL: As I wrote in the acknowledgments, “a secret stands at the center of ANNIE'S GHOSTS, but a family stands behind it.” My siblings have been involved since the beginning, and I feel fortunate to have their support, which doesn’t mean that everyone sees the story the same way. The manuscript made the rounds of the family, and generated a lot of discussion --- which I benefited from as I worked on the revisions.

Q: Your cousin Anna Oliwek, the Holocaust survivor who argued with your mother about her secret, is such an interesting character. When did you know you would visit Radziwillow, where Anna’s family died in the Nazi-led massacre of the town’s Jewish population?

SL: As one of the few people still living who had met Annie and talked with my mom about her secret, Anna became a central figure in the book in ways that I hadn’t anticipated. Her story of surviving the Holocaust, and how that shaped her worldview, made her even more compelling.

The more I interviewed her, the more I felt the pull to visit Radziwillow, to see the mass gravesite, to look for some hint of my family’s past there --- although I had no illusions that I would find the Radziwillow of Anna’s youth, let alone the Radziwillow that my grandparents left before World War I.

Interestingly, Anna couldn’t understand why I wanted to go to Radziwillow. She associates the town, and its inhabitants, with the massacres there and the murders of her mother, brother and sister. When I called her from Ukraine to tell her what we had seen, and to ask her a few questions before our return to the town the next day, she warned me several times to be careful where I went, and who I approached.

Perhaps that’s why it was gratifying to find people in Radziwillow whose families had sheltered Jews. I knew of the Radziwillow where Jews had been massacred, but had no knowledge of this other Radziwillow.

Q: The book memorializes Annie in a way that was never done in life or at her death. Yet, we don’t know much about her day-to-day existence. As a reader, I found myself needing to believe that every day was not a living hell, that she did have some happiness. What about you --- how did you cope with the knowledge of her suffering and loneliness?

SL: I don’t know if her life was a living hell, but it was a circumscribed and unrelenting existence, in a setting that had little to offer her. The low point for me: When I read in a 1972 hospital report, written just months before Annie’s death, that she was “incoherent and irrelevant much of the time.” How long had she been that way? Certainly not in the late 1950s when Anna was driving my grandmother to see Annie at Eloise.

I couldn’t change what happened to Annie, so I tried to focus on how someone with Annie’s disabilities would fare today. Could she work? Could she live in a group home and achieve that independence she craved?

The answers I uniformly got from experts --- that, yes, she probably could make it today --- gave me some small comfort that we have learned something from the suffering and loneliness that characterized Annie’s life, and the lives of others who languished in mental hospitals of the mid-20th century.

Q: This really seems like a book that tells the stories of three Jewish women during the first half of the 20th century: Annie, your mother, and Anna Oliwek. In a lot of ways, you've written women's history as much as family history. What are your thoughts on that?

SL: I’m pleased that you think so! I can’t claim that I set out consciously to write women’s history, or even family history. My goal was to wear the skins of every major character in the story, to understand how each of them saw the world, and to understand how the world saw them.

Annie, my mom and Anna Oliwek all represent different strands of that universal longing for freedom and its benefits. That longing, as much as secrets and secrecy, permeates the book.

© Copyright 2009, Steve Luxenberg. All rights reserved.

• Click here now to buy this book from Amazon.