Interview: Scott McCloud

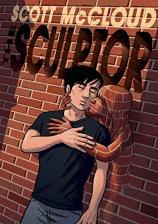

Scott McCloud, comics' most eloquent and prolific theorist, is best known for his explications of the form: UNDERSTANDING COMICS and its follow-ups, REINVENTING COMICS and MAKING COMICS. But starting in the late 1980s --- even before he turned to non-fiction --- McCloud began his comics career with an American superhero manga series, Zot!. And this year, for the first time ever, McCloud puts his talents to an original graphic novel, the absolutely monumental THE SCULPTOR. Here, McCloud sits down with The Book Report Network staffer and GraphicNovelReporter site coordinator John Maher to discuss his newest work, his history in comics and why he prefers the pen to the hammer and chisel. Note: This interview is chock full of SPOILERS!

The Book Report Network: How did the idea for THE SCULPTOR --- a down-and-out artist, literally sacrificing his life for his art --- come to you, and how did you grow it?

Scott McCloud: The basic premise came to me when I was quite young. One of the entries in a binder that I had owned in high school or in college --- I’m not sure exactly when --- I had jotted down the idea of this artist who could literally shape something with his bare hands. I held on to this idea for a very long time, and I was moving away from the superhero stuff of my youth, but I liked this story.

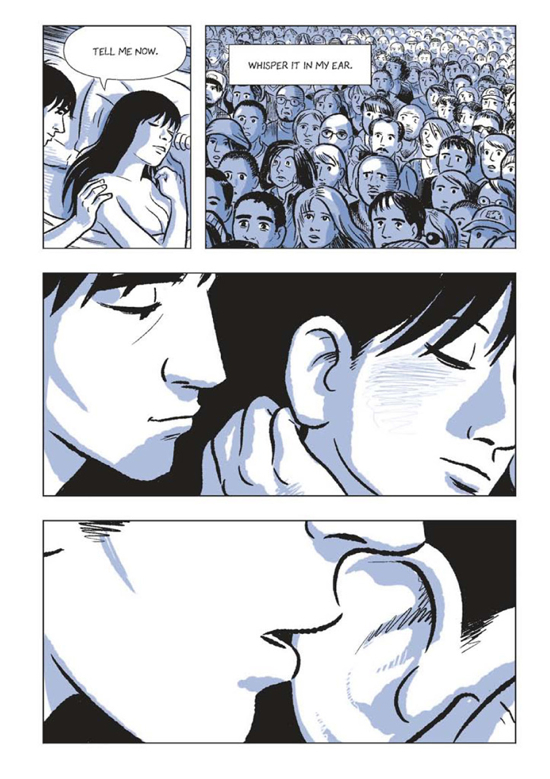

It really came into focus for me in my 20s, especially when the character of Meg came into the story. She didn’t have a name yet, but she was inspired by my wife, Ivy, who I was secretly in love with at the time. When she came into the story I realized there was something to it, and as the years went on, I had other stuff to do. Comics take a long time to complete. This idea had kicked around in my head for a while now --- it was like two or three decades.

So all I could do [for years] was think about this story, and that proved to be really healthy. And it took five years to actually make it. In this case, I added a lot to the process because I had a very understanding and encouraging editor and a publisher that gave me the space to get everything right. It’s a real slow-cooked meal in the end, and I think it’s a better book for that.

TBRN: How has the story changed along the way?

SM: During the two years when all I was doing was restructuring the layouts, the most important thing was coming to understand what the story is ultimately about. You can have all the plot points down and not fully understand what the heart of the story is…. Ultimately, you need to know what the story is about in order to write it, but you need to write it in order to know what the story is about.

I did four passes. I did this very tight comprehensive rough for this story, nearly 500 pages, and I re-did it and re-did it and re-did it again, over the course of four years. And that was before I drew a single finished panel!

The art in THE SCULPTOR is striking, juxtaposing a very recognizable, down-to-earth New York with David’s often surreal works. Perhaps most striking, however, is the color choice --- the entire work is done in black, white and a range of blues. What made you choose to limit yourself to one primary color?

SM: I was limited in some ways by practicality. The fact is, I really like having control over the full process. But if I worked full color, I would have had to give up some of the control.

I’m too much a control freak. I needed to do it all myself. But I also felt that if it was pure black and white, I might not have been able to communicate the form that was in the panels, so with that second color I could clarify the form…. When you have that intermediate tone you can clarify the shadows, or use it to make those foreground elements pop. When the eye lands on that page, it has that all-at-onceness --- you instantly see all the form.

The cover, however, is multi-color. Was that to give it maximum shelf appeal?

SM: It never really occurred to me that I could do a limited palette cover, although the French version of the book has a limited palette cover and it’s gorgeous.

I really loved what First Second did with the images underneath --- it has these very striking images inside the cover of the two protagonists.

TBRN: I’ve read that you frequent museums when you travel. Do you have a favorite sculptor or a favorite work?

SM: You know, it’s kind of funny, but I really like David Smith’s early work. [Laughs.] The more complex stuff I thought was really cool. I like Louise Nevelson. I really like the opportunity to be in the room with one of Serra’s big rusted slabs, those things are great --- Richard Serra. I love Brad Koozie. But I’m certainly not even remotely an expert in modern sculpture or sculpture generally. I just enjoy it. I have a very uncomplicated relationship with modern art…. I just enjoy it. It’s fun, and bracing. But historically, if were talking before the 20th Century, i think my very favorite historical art is from pre-Columbian Latin America. Something about it really speaks to me.

TBRN: Have you ever worked in the medium of sculpture, or is it just something you admire?

SM: No, very little. As a matter of fact, as a kid, I was always at a disadvantage when it came to anything 3D. I was happy to draw and I was happy to paint, but as soon as it came to anything with structure and space, I was frightened of it. It was too messy.

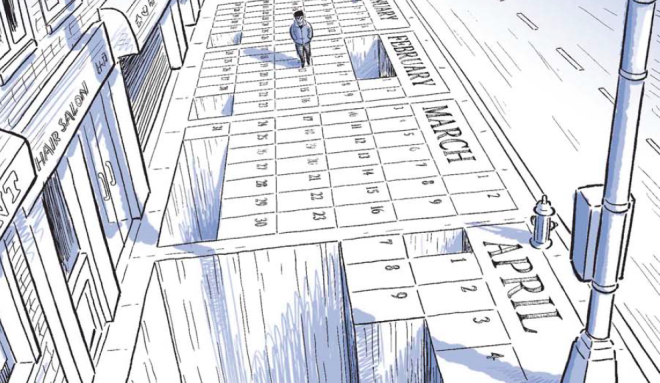

TBRN: Your book pays a great deal of attention to the passing of time. Clocks and calendars figure prominently, as do markers of time and place --- I’m thinking of David seeing a Santa Claus figure standing in the snow with a sign saying “10 Days Left Until Christmas.” How do you think the comics medium allowed you to handle this in a unique way? If you had just a limited amount of time to create a project yourself, would you find that challenging or frightening?

SM: Because comics trades in static images, the challenge for a cartoonist is to select images that have staying power, images that burn themselves into your retina and memory and stay there until the next image comes along, and the next one.

I’m forever on deadline myself when I'm working on books, so I’m sure that’s had something to do with it. It’s crossed my mind --- if I were ever diagnosed with something, how would I use that time? I’m actually halfway between David and Meg. I’m halfway between my protagonists. I’ve come to accept the value of day-to-day relationships, but also the value of sitting and working long hours by myself.

TBRN: THE SCULPTOR is a lot of things: a love story, a coming of age story, something of a Faustian bargain, and, in its way, a superhero story. How did you knit together these pieces?

SM: That comes back to this notion of coming to understand what your story is about. When you have that, you know where the puzzle pieces connect. That’s your guiding light --- that’s your lighthouse --- and I know I’m mixing a metaphor here, but that ensures that anything that comes your way is all going to fit and create a single whole. And that was the goal, to create something that has a solidity, a kind of an organic quality, when you're creating a book. If things go well you’re creating a living being, and you want to make sure all those veins and passageways work. You want it to have a breathing heart. To breathe quietly on the shelf.

TBRN: As a sculptor, David is used to being the shaper --- the one who changes what's around him into new forms. How is David shaped by his experiences and by his emotions: Love, fear, regret?

SM: I think you could make a serious case, if you took that as a thesis --- 9th graders, take note! --- you could probably make a solid essay on why Meg is the title character in some ways. There was a scene that got cut out --- it didn’t quite fit, but it had the germ of something that I liked --- where a character named Finn, who’s a kind of a rival for David, shows him a tattoo that he got, and David’s friend Ollie explains that David doesn’t like tattoos. He says that David doesn’t understand why anybody would want to be the canvas for somebody else’s art. And this is something that I imagined him gradually learning --- that he had become that, where Meg was concerned. Somehow the discussion didn’t quite work, so I let it go.

TBRN: What has been your favorite part of the process involved in writing a graphic novel like THE SCULPTOR?

SM: My favorite part of this was finally experiencing what it is to be a writer, to feel like I was engaging seriously with the challenges implicit in that word. I think I have a tremendous amount still to learn about writing, but at least now I’ve had a taste of it. I’ve experienced that sensation, and I hope to experience it more in the future.

TBRN: THE SCULPTOR ends with a non-fiction epilogue, of sorts, in prose with no accompanying pictures. Do you think of this as part of the graphic novel? What made you choose to include it?

SM: Yeah, I think that everything down to the typography is part of the graphic novel, and I do hope people read the epilogue… certainly those last two pages of the afterword, to me, are part of the experience of reading it. And I hope that when people read the last pages of the comic, they continue to turn the pages and read the last pages of the story. I think it’s important that they return to this world…. It’s now time to build that bridge to the world we live in, and I guess those words stand on that bridge, overlooking both: the world of fiction and the world that never quite goes away.

TBRN: Have you found that your creative processes and methods have changed since writing Zot! in the late ’80s and early ’90s? If so, how?

SM: Yes, but that’s no surprise, because every time I do a project I change my creative method. At my heart, I’m still a formalist, I’m still a tinker, I’m still an inventor --- and that’s what we do. A new project is a new opportunity to reinvent the process.

I think that in Zot! I was creating proof-of-content pieces, but to me they were trying out ideas, they were trying out forms. Sometimes they worked, sometimes they didn't, but I felt like I was still on my training wheels. I like some of those stories, especially the later stories, but I look at them now and think, “Here’s a writer who could do something serious down the road.”

TBRN: Like Zot!, THE SCULPTOR seems heavily influenced by the Japanese comics tradition. When did you become interested in the similarities and differences between Eastern and Western comics? How did you find a way to combine those styles so smoothly?

SM: My interest in manga goes back almost 30 years now, really 35 years. I saw my first untranslated manga in college…. [But] i don’t see [my work] as infusing the comics with a Japanese flavor so much, just recognizing which culture did a better job portraying motion, portraying a sense of place. I just picked and chose from many comics traditions…. this is almost as much a European graphic novel as it is a Japanese graphic novel, because it’s so invested in world-building…. That’s more in the Franco-Belgian tradition, where one of the things you have to do is create a sense of place, of world.

That integration you mentioned, that comes with time. If you have a stylistic influence that you apply for decades, it’s going to become part of your metabolism. Same with culture. The American culture has now digested some of those forms that are now no longer floating on the surface. They’re part of American comics now.

TBRN: You’ve worn many hats in your time in comics: critic, creator, editor, speaker and educator. Just in the past year alone, you edited THE BEST AMERICAN COMICS 2014 while presumably putting the finishing touches on THE SCULPTOR. Did you find it difficult to perform two roles at one time, or find the comics you chose influencing your own work?

SM: I need to have things very orderly. I need to have one thing on my desk, and to have a rigid schedule. I rarely have that. [Laughs.] But when I have that rigid schedule, I’m really quite happy.

Even though I was busier [this past year] than I've been in my entire life and it was just absolutely insane, it was also insanely productive. And I do like being productive. So it wasn’t so bad. There are worse things. As far as the influence going back and forth, in a lot of ways there was a kind of slingshot thing going on. When you’re working 11-14 hours, seven days a week, you don’t have a lot of time to read. You can listen to a lot of podcasts, but you can’t do a lot of comics reading. And THE BEST AMERICAN COMICS 2014 was really an opportunity for me to dive back into that world of comics, which I love.

TBRN: How did you translate comics theory --- which you made a creative endeavor all its own --- into comics practice?

SM: Creating life on the page was something I think had largely eluded me. I know the characters from Zot! felt alive to some readers, so I don’t want to pretend that I’ve never accomplished it at all before, but I felt that I had a deficit when it came to bringing my characters alive. They tended to look stiff, drawn, overly-calculated. There was a dry quality to the comics I had done to that point, and that was one of the things I wanted to get beyond. So it involved a lot of hard work, and some study, and it involved getting some friends to model, and that helped a lot…. The real measure of whether I had made the transition from theorist to storyteller is if readers thought about the theory as they read or if they were spellbound by the story.

In the storytelling, I thought a lot of it had to do with capturing the rhythm of the way people act around each other…. I was trying to capture the human theater: the way people gesture to one another, precise facial expressions. If I could get all that stuff right, that would finally capture a reader in such a way that they would no longer look at the panel structures or the bleeds or my aspect-to-aspect transitions or whatever. They could just get beyond all that shit and to what really mattered --- which is human beings doing things, feeling things, achieving things on the page.

TBRN: How does THE SCULPTOR exemplify the techniques unique to sequential art that you outline in your critical works like UNDERSTANDING COMICS?

SM: As a matter of fact, that’s been my goal for so many projects. But this time, if I wanted to really achieve my purpose of becoming that other kind of artist, the kind that’s not so calculated, it couldn’t be just about comics. It had to be a story first. So I see this as a story that exists independently of its medium in some way --- that is just storytelling.