Interview: August 14, 2025

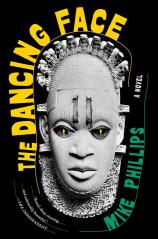

A Black university professor plans a burglary to “liberate” an African sculpture from a London museum in THE DANCING FACE, a blistering, original thriller that examines the powerful link between identity, sacrifice and possession. In this interview conducted by former publicity executive Michael Barson, Mike Phillips discusses how he felt when he learned that his book, which was originally published in England in 1997, was being released in the US for the first time. He also explains what inspired him to begin writing crime fiction and talks about a possible series adaptation of THE DANCING FACE.

Question: You’ve remarked that you hadn’t reread THE DANCING FACE since it was first published in England in 1997. But have you recently given it a look? If so, how does it strike you now in 2025?

Mike Phillips: When I heard that THE DANCING FACE was soon to be published in the US, I searched my shelves for a copy and began flipping through its pages. I was soon gripped --- astonished by the depth of emotion I was feeling, and, at another level, deeply impressed by my insistence in working through the issues of identity that were concerning me at the time.

A couple of passages brought tears to my eyes, and it struck me then that all of it was really about my own feelings and my own history. Not much had changed, and I was reading the familiar names of the places where I grew up: London, the Midlands, the West Country, Alexandra Palace, Euston Station. All this was also about my youth, but surprisingly, all of it felt bang up to date, as if I'd written it last week after driving past one of those places on my way to a soccer game.

Another thing that strikes me is that when I began writing THE DANCING FACE, I was more or less fed up at being (dismissively) described as “a Black crime fiction writer” and having my work patronisingly compared with my white contemporaries. I also disliked the inevitable comparisons with Black American writers. Don't get me wrong. I loved all those guys, especially writers like Walter Mosley, but my vision had emerged from a different place and from different experiences, a fact that few or none of the critics seemed able to grasp.

Reading THE DANCING FACE again, it strikes me that I had underestimated its impact because, now, I still knew everyone in it, and all the debates were real. And as I turn the book’s pages now, I remember that the impulse as I wrote was about declaring who I was. And that still comes through loud and clear.

Q: The issue of reparations that fuels the plot of the book was a bit ahead of its time in 1997, wasn’t it? But it couldn’t be more timely today. Are you a seer?

MP: Yes, I probably am a bit of a seer, like all the other good writers of fiction. (I paused before I wrote this down. Then I thought, Bugger it, it’s true). Back in the ’90s, the issue of reparations still belonged on a list of “crazy” demands, the purview of Black activists and “extremists.”

On the other hand, anyone working in the sector of museums and galleries in Britain was familiar with a series of arguments about the Elgin Marbles and the remnants of Egyptology held in the British Museum. West African works of art had some way to go before achieving the same status, and that’s where my interest in the issue began. But there was something that grabbed me, in a peculiar personal way, about the features of the Benin statuettes.

My days of student radicalism had constructed Africans as a mass of hapless victims, or noble rebels, a continent of Nelson Mandelas on steroids. The faces of West African statuettes told me something different. These were more than victims, or subjects of other people’s desires. Enigmatic and challenging, they had become the source of endless curiosity, impossible to categorise under the world views I had been taught in the classroom --- forever beautiful, forever cruel and indifferent, forever and always themselves.

This is one of the reasons I love the new cover of the book. While I wrote, I kept a similar picture on my desk, and in my imagination it was leading me from the beginning up to the end.

Q: How did the news that the book was about to see its first US publication after more than a quarter century strike you when you first heard of it? Was the feeling utter joy, or was that mixed with some trepidation?

MP: My first reaction was one of surprise, partly because I had the sense that some aspects of the tale had already been stolen (without reference to me or my story) for use in other, rather different contexts. My second reaction was utter delight, mingled with surprise that an American publisher such as Melville House would take the trouble to look past the conventions of Los Angeles and Chicago, or the strictures of Black Lives Matter, to choose the work of a British Black writer, already published 30 years ago. At no point did I feel any trepidation. My reputation, for good or ill, has long been established in the place where I live (England), and the book appearing this way again can only help.

Q: What are a few of the books that inspired you to begin writing crime fiction in the ’90s?

MP: Weirdly, my love of crime fiction began many years before I started to write. I left Guyana in my early teens, but before that we lived in Shell Road, Kitty Village, next door to an Indian couple, the Bissesars. Their kitchen boasted a long shelf packed with books, and my practice was to slip next door and sit on the stairs reading the sort of stories I’d never seen anywhere else. While Mrs. Bissesar went about her household tasks, I’d be sitting there turning the pages of paperbacks --- Raymond Chandler, Mickey Spillane, Joseph Conrad --- half-listening to her singing in Hindi.

I think these were experiences that (fatally) shaped my tastes, so when I began writing novels 30 years later, I was once again the small boy sitting in the sun, making up stories to the lilting sound of Hindu chanting.

Of course, by the time I started writing crime fiction, my models had changed radically. I was reading Graham Greene, Eric Ambler and Len Deighton with varying degrees of interest. Later on, Martin Cruz Smith’s GORKY PARK was a favourite. By then, I had stood in front of Pushkin’s statue in Moscow, wondering. The work of all these writers seemed to be pushing me towards a discovery of my own tastes and desires.

Q: Do you still keep up with crime fiction? Who are the authors who have impressed you most over the past 10 years?

MP: It would be more precise to say that I keep up with trends in crime fiction. In the last 10 years or so, I’ve been most impressed by the approach of individual Scandinavian and Italian novelists --- Stieg Larsson, for example. On the Anglophone side of things, where are the new Carl Hiaasens, Elmore Leonards, Walter Mosleys and Ed McBains? The answer might be that writers seem to be migrating to the “writers rooms” in LA before having to get anything down on paper. But maybe that’s just my cynicism.

Q: Will we see an adaptation of THE DANCING FACE as a BritBox series on the telly one of these days? It seems to be a very worthy candidate for the miniseries treatment.

MP: Yes, yes and yes. It’s in the hands of a top producer, Nicola Shindler of Quay Street Productions, along with a talented young African producer, Denzel Adebayo. They’re looking to get started on making the series early next year. Fingers crossed!