Interview: April 6, 2007

April 6, 2007

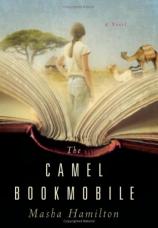

Masha Hamilton has worked for the Los Angeles Times, The Associated Press and NBC-Mutual Radio, and is the author of THE DISTANCE BETWEEN US and STAIRCASE OF A THOUSAND STEPS. In this interview with Bookreporter.com's Alexis Burling, Hamilton discusses the real project that inspired her latest novel, THE CAMEL BOOKMOBILE, and elaborates on some of the themes covered in the book regarding the clash of disparate cultures and the ways in which Americans approach issues overseas.

She also explains why she waited until after the manuscript was in its final editing stages to visit the country where the book is set, compares and contrasts journalism with novel-writing, and shares what she hopes readers will take away from reading her story.

Bookreporter.com: What inspired you to write THE CAMEL BOOKMOBILE?

Masha Hamilton: My daughter told me about the actual camel bookmobile one day, and the thrust of the novel came to me at that moment, in one surprising swallow. I saw Scar Boy and Kanika and the teacher with his wife and the librarian, Fi. Of course, it took me three years to write it and flesh it out, develop the images and learn more about the characters. But I knew the story basics that very day.

Bookreporter.com: THE CAMEL BOOKMOBILE is made up of chapters, each told from an alternating character's point of view. Why did you choose to tell the story this way?

MH: This is a multi-character story, and each character became very alive in the course of writing the book. Each spoke in her or his own voice, full of personal concerns: Mr. Abasi, who thinks his camel is his mother reincarnated; Scar Boy, who was viciously attacked by a hyena; beautiful Jwahir, with her proud sense of feminism and disdain for what she calls "A Cat On A Hat" --- a book that she says comes from the space between one's teeth; Matani, with his desire to spawn a son, and his superstition about the "black-fronted mosquito-eater" (a bird I made up, by the way). The camel bookmobile changes each character, and the differing ways in which they are altered intrigued me.

BRC: In the first "The American" chapter, Fi's good friend Devi says to her, "You know, there's lots of illiteracy in this country." This is quite a pointed comment and one that reflects a certain strain of thinking prevalent in the world today. "Why fix it over there when we've got the same problem over here?" Would you agree that this is the case? How do you reconcile this with Fi's approach to helping others elsewhere?

MH: Fi responds by noting that in the region where the camel library will operate, they don't have books at all; most don't even have the opportunity to learn to read yet. She approaches her work with a great deal of idealism and the viewpoint that she is going into this culture as the donor and the teacher. In fact, of course, she is taught, and she receives as much as anyone else in the story.

BRC: Devi also sarcastically says at one point, "That means not everyone you meet is so thrilled to see a white lady and her books?" Again, a legitimate point. Here we have a privileged white American seeking her own fulfillment by helping the deprived people of a poor, African country. Did you have any concern that the audience might consider this work more self-involved and narrow-minded instead of altruistic as there is so much else these people need, like food, water, clothing and proper shelter?

MH: In fact, that issue of food and water versus books is raised in the novel, and Fi responds by saying that she believes books and education will lead to improvements in these other areas by creating greater possibilities for each person. But at the same time, I wanted Devi to raise an important point. I wanted to explore the idea that even when we Americans have the best of possible intentions --- what could be more positive than bringing books to the bush? --- our ignorance of other cultures can work against us, even causing mistakes of tragic proportions. And certainly Fi experiences this.

BRC: Conversely, some readers might find Fi to be a bit naïve in her views and opinions about the bookmobile project and her role in it. Would you agree or disagree with this assessment?

MH: I found Fi to be very likable but, yes, idealistic to the point of naiveté in the beginning of the story --- and I think this is a realistic depiction of the way we Americans often involve ourselves in issues overseas. Even the best of intentions, when not backed by solid experience of the others' cultures or histories, can lead to devastating mistakes. I felt by the end, though, she had deepened and begun to understand that she had as much to learn from these people as they did from her.

BRC: One of the main conflicts in the book deals with disparate forms of tradition born from two dissimilar cultures. Some of the villagers of Mididima are outraged by the Bookmobile's introduction of a new type of tradition into their homes: Western books (mostly written in English), Western ideas, Western traditions. They are afraid that if their children read Western books filled with new, more modern ideas, they will no longer respect their elders and the old tradition (mainly oral) that they have been passing down for centuries. This is a powerful and deep-rooted conflict. Can THE CAMEL BOOKMOBILE be seen as an allegory for what's still taking place in the world today? Is there a lesson to be learned?

MH: I think some threads of this story are fun, some deal with love and sex, some with religion, and yes, for me, some themes have to deal with how we Americans involve ourselves in the greater world, and both the value and the shortcomings of that involvement. I thought a lot about that issue while I was writing the book --- how could I not? It currently is affecting our country daily, and it is one of the book's major themes.

BRC: In the book, Fi has a conversation with the librarian, Mr. Abasi, in which she says (about the villagers of Mididima), "They are smart. They deserve a chance. And I can help them. Without an education and exposure to the modern world, they have no future." He responds later on by saying, "You love the idea of what you think you are accomplishing…But they have their own approach to their lives. Don't assume it needs to change." This is so telling. Might you care to elaborate on the significance of this exchange in relation to the book? To the real world?

MH: You know, I love that you got this point and several of your great questions reflect that, but I do want to stress that I didn't want to write an essay or stand on a soapbox. I wanted to write a story, a good read, multi-layered and complex, that dealt with a number of issues, like this. But I also wanted to include what happens when you love the inappropriate person, as several of the characters do, how art can save an outcast, how books can build bridges, and how experience writes a kind of graffiti in our hearts --- and that graffiti lasts even as we move on to a different time and place.

BRC: How did you prepare for researching/writing this book? Did you travel to Kenya?

MH: I only traveled to Kenya after the novel had sold and was in the final editing stages. At that time, I traveled into the bush with the real camel library. I waited because I wanted the story to be more than reporting. I wanted the fiction to have its own inner truth and resonance before I spent time with the real-life camel librarians and their patrons.

BRC: Did the story change at all from when you first started writing it to its final draft?

MH: It deepened with each draft. Also, all the mosquito quotes that appear periodically throughout the book are invented; I worked with them to try to subtly reflect theme and action as the writing process went on.

BRC: What would you like your readers to take away from their experience with THE CAMEL BOOKMOBILE?

MH: A good story, and a sense of connection to another world.

BRC: You worked as a foreign correspondent for The Associated Press, covering the intefadeh in the Middle East. You were a Moscow correspondent for the Los Angeles Times, covering Kremlin politics under Gorbachev and Yeltsin, and civilian life during the collapse of the Soviet Union. You traveled to Afghanistan as a freelance journalist to report on the country's reconstruction efforts. How has all of this experience shaped your vision and your voice as a writer?

MH: I am very, very interested in the world at large, and feel myself to be a small part of that larger world. I think we, as Americans, understand ourselves even better when we see ourselves through the lens of others.

BRC: How do you find writing novels different from working as a reporter? Do you favor one over the other? How do you quiet the reporter in you when working on a book…or do you?

MH: Writing novels allows me to go within, and reporting keeps me part of the larger world "out there." I truly value both, though I believe that it is ironically possible to find a deeper kind of truth in fiction. As for quieting the reporter in me, that's why I waited to go see the real camel library.

BRC: Share with our readers the latest about The Camel Bookmobile Book Drive that you are working on.

MH: Though THE CAMEL BOOKMOBILE is a novel, the camel-borne library actually exists. It operates from Garissa in Kenya's isolated Northeastern Province. Initially launched with three camels on Oct. 14, 1996, the library now uses 12 camels traveling to four settlements per day, four days per week. The camels bring books to a semi-nomadic people who live with drought, famine and chronic poverty. The books are spread out on grass mats beneath acacia trees, and the library patrons, often barefoot, sometimes joined by goats or donkeys, gather with great excitement to choose their books until the next visit. But of course, the bush is hard on books and the traveling library badly needs more. So, a group of us authors began a drive that soon expanded to include librarians, publishers, agents and booklovers. You can contribute books in English, Swahili (the two official languages of Kenya) or Somali (the native language for most of the library patrons in the region.) Please take a look at www.camelbookdrive.wordpress.com, and if you can send a book or two, do.

BRC: Do you prefer to read a specific genre of books? What are some of your favorite books that you'd recommend to your readers?

MH: I love literary fiction and lots of nonfiction. My favorite book is always the one I'm reading now; in that way, like many of us, I'm fickle. Right now, I'm reading Dave Eggers's WHAT IS THE WHAT?

BRC: What are you working on now, and when might readers expect to see it?

MH: I'm working on a novel manuscript called "Thirty-One Hours" that I hope will be ready for my agent soon. It takes place in New York City over 31 hours and, like THE CAMEL BOOKMOBILE, is told from multiple viewpoints.

Thanks for all your thoughtful questions. It was fun answering them.