Author Talk: May 8, 2009

AUTHOR TALK

May 8, 2009

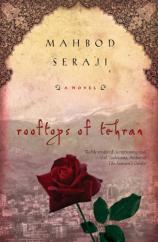

Mahbod Seraji's debut novel, ROOFTOPS OF TEHRAN, is a coming-of-age tale and love story set in 1970s Iran. In this interview with his editor, Seraji sheds light on little-known facts about Persian history and attempts to clear up cultural misconceptions about his home country. He also talks about some of the challenges of assimilating he faced shortly after emigrating to the United States, muses on cultural differences between America and Iran, and shares details about a book he's working on now.

Question: You’ve lived in the United States for thirty-two years, since you arrived at the age of nineteen. What inspired you to write your first novel at this point in your life, and how much is it based on actual events?

Mahbod Seraji: Thank you for letting everyone know that I’m an old man!

Q: Old? I don’t see how that’s possible since I’m several years your senior, and I’m in the prime of life!

MS: Ah, but it’s well known that editors remain forever young. Anyway, getting back to your question, I’ve wanted to write ever since I was ten years old when I read my first book, Jack London’s WHITE FANG, a translation into Persian from the original English, on the same rooftop that’s depicted in this novel. But life always got in the way of my writing. Then, a few years ago, I lost my job, and that was the best thing that ever happened to me. I started writing and haven’t stopped since.

As for the novel, some of it is based on actual events, but not all of it. So it’s important to point out that this is not an autobiography. It’s also important to note that I fictionalized Golesorkhi’s trial by changing the date and some of the words he used defending himself in court.

Q: You came to this country speaking very little English, but have obviously mastered the language. How did you accomplish that, and what was it like to face the formidable challenge of learning a foreign language, in a strange new land, without the support of family nearby?

MS: I wish I could say that I’ve mastered the English language. There’s always more to learn! Learning a new language is a challenge faced by millions of people living in countries other than their homelands, and learning English is hard. One of the hardest things I’ve ever done. When I first came to the United States, I ate Big Mac, Small Fries, Small Coke for six weeks because that’s all I knew how to order. I’m sure the McDonald’s Corporation’s revenue skyrocketed that quarter! The trick to learning any foreign language lies in assimilating yourself into the culture of your host country, mingling with the native speakers, watching lots of television, and --- the one factor that unfortunately many people ignore --- reading as much as you can. The first non-textbook English-language book I read was Erich Fromm’s ART OF LOVING. And for me that translated into the Art of Loving to Read. Since then, I’ve been reading religiously. Some of my favorite authors are named in ROOFTOPS OF TEHRAN: Emile Zola, Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Maxim Gorky, Jack London, John Steinbeck, Bernard Shaw, Noam Chomsky, and many others.

Q: In the novel, you convey the love-hate relationship that Persians had with the United States in the 1970s --- and some very funny misconceptions. The U.S. was the power behind the oppressive Shah, and thus their hated enemy, yet also a place whose freedoms and opportunities beckoned to them --- what an emotional tug-of-war that contradiction must have created! What surprised you about American society when you arrived here, and what misconceptions about Iran do you still encounter among Americans?

MS: I don’t want to generalize or offend anyone in either country, so please forgive me if I do. Americans are wonderful people: kind, accepting, honest. They tend to do as they say and act in fair-minded, balanced ways. This country’s higher education system is excellent, both in terms of quality and accessibility. Here, anybody can go to college. Many countries simply can’t accommodate many students. And by the way, most people who came here in the seventies came to get an education. They didn’t wake up one morning and say, “I’m going to America to be free.” They said, “I’ll go there to get an education.” That’s an important distinction. It was only after they were here for a while that they fully appreciated the freedoms we enjoy here.

What surprised me when I first arrived was how, despite the abundance of information available, only a small number of people knew about, or had any interest in knowing about, what was happening in the rest of the world. To a large extent, that’s also true today. I was shocked, for example, to learn how little most people I met knew about Iran. I remember once during a class discussion, while attending college in the ’70s, I mentioned the CIA’s successful 1953 overthrow of Mosaddegh, the only democratically elected prime minister in the history of Iran, and half of the class accused me of lying because “the American government just doesn’t do bad things like that.” Even the teacher said I had my facts wrong.

Some Americans have a blind faith in their government. I mean, think about it. Institutional democracies such as America’s must not support, in fact should oppose, undemocratic actions, movements, or forces anywhere in the world, at least in theory, right? But that’s not always true in practice, and that’s what some Americans have a hard time believing or even comprehending. Consider the situation in Iraq today, the summer before the U.S. presidential election. There are still people who are looking under rocks for weapons of mass destruction. They genuinely can’t fathom that their government deceived them.

Iranians and Americans are on the opposite ends of the spectrum on this issue. It might take an act of God to convince some Americans that parts of their government are corrupt, but at the same time, you cannot, under any circumstances, persuade an Iranian that his government is not corrupt! Fascinating, isn’t it?

As for current Americans’ misconceptions about Iran, I see a lot of misrepresentation in the media. Because the governments of Iran and the U.S. don’t get along, we tend to mischaracterize the people of Iran as evil. The media immediately conveys images and information that dehumanizes the Iranian people. Likewise, we’re encouraged to forget that our so-called enemies have feelings and are capable of love and friendship. We see them as so dissimilar, we can’t imagine that we may actually have a lot in common. It’s really sad for me to see how far apart these two great nations have fallen.

Q: Americans know very little about Persian history. I was especially interested to learn of the long periods of occupation and oppression by foreign invaders that Persians have endured over the centuries. Are there obvious ways in which that history continues to shape Persian culture and society?

MS: Iran is one of the oldest civilizations in the world, with an interesting, tumultuous history. Three massive invasions have left indelible marks on our culture, psychology, literature, and arts. These invasions included that of Alexander the Great, called in Iran “the cursed Alexander”; the Arabs; and Genghis Khan. Millions of Iranians lost their lives in those invasions, and were subjected to unimaginable violence, and modern-day Persians have not forgotten. In between those invasions, our people suffered grim atrocities committed by our own homegrown despots. Each nation’s history, and the way in which its people respond to it, help define the culture of that country. So because of our history, we tend to have a grim and fatalistic outlook on life. We suffer from pessimism. We’re suspicious of authority figures, always feel victimized, and unwaveringly believe in the existence of unseen forces that control events from behind the curtains. We see strings where there are no puppets. At the same time, it’s important to note that we are a resilient people and we can survive almost anything; nothing can break the passionate Persian spirit. We love to argue --- not discuss, but argue politics. Family is very important to us. Our friendships are legendary. We are a generous nation, kind and extremely hospitable. Even now, many Americans who visit Iran talk about being overwhelmed by the warmth and hospitality of the Iranians they meet in public places. You hear stories of cabdrivers not taking money from their American passengers, restaurant owners not charging Americans for food, regular people going out of their way to help Americans. I know some readers may find this hard to believe, but it’s true.

Q: Do you still visit Iran? How has it changed since you were growing up there?

MS: I do go back for visits. My father still lives in Iran. I can’t find my way around Tehran anymore --- it’s grown so much! And people are different. There is a feeling of melancholy in the air that you sense immediately upon your arrival. But, amazingly enough, as you get back into the daily routine of life, you rediscover that indomitable Persian spirit, that “we’ll survive anything” attitude!

Q: I think of Iran as a rocky, barren, hot desert country. Yet when you sent me some pictures of Tehran, I was surprised to see that it’s quite green, with full-sized trees, and that it snows there. Can you give us some idea of the size and geographical diversity of the country? And how much of a middle class does Iran have, compared to those who live in poverty?

MS: Contrary to popular belief, Iran is one of the most mountainous countries on the planet. It’s actually a pretty large country, sixteenth in the world in terms of its size, about one-fifth the size of the USA, with a diverse population of over 70 million people consisting of such ethnic groups as the Azaris, Baluchs, Kurds, Lurs, Assyrians, Armenians, and many more. There are two large mountain ranges, Zagros and Alborz. The highest peak, the volcanic but thankfully dormant Mount Damavand, is 5,678 meters (or 18,628 feet) high. It’s an easy-to-remember number and used to be a favorite geography quiz question, when I was in high school in Iran. There are two great salt deserts in the eastern part of Iran, mostly uninhabited. The climate varies from region to region. Winters can be bitterly cold with heavy snowfalls in the northwest. Spring and fall are absolutely gorgeous regardless of where you are. And summers can be hot and dry in some areas, and very humid in others, particularly in the north by the Caspian Sea and in the south near the Persian Gulf. In terms of wealth, the United Nations considers Iran a semi-developed country; its GDP is ranked fifteenth in the world. So Iran is not one big desert wasteland like many people think. Because of the type of work I do, I’ve traveled widely throughout the world, and the area by the Caspian Sea is one of the most lush and beautiful I’ve seen anywhere. In terms of standard of living, according to the figures I’ve seen on the Internet for 2007, approximately 18 percent of the population in Iran lives below the poverty line (compared to 12 percent in the U.S.). And of the almost 30 million people who make up the workforce, 15 percent to 20 percent, depending on whose statistics you believe, are unemployed. So there is a middle class in Iran, but I believe it’s shrinking.

Q: Now that you’ve answered some of my many questions about Iran, let’s get back to the book! One of the reasons I was originally drawn to the novel is because the love story between Pasha and Zari is so romantic. Are you in particular a romantic, or is that a Persian quality?

MS: My friends will tease me for the rest of my life if I even hint at having a single drop of romantic blood in me! My wife may go into shock. So let’s be careful with this one! I think readers will connect with Zari and Pasha because everyone remembers the first time they fell in love. Zari’s and Pasha’s youth puts them in an impossible situation to begin with, and if you add their restrictive social conventions and Doctor’s state of affairs, their situation becomes hopeless. And by the way, that is the dictionary definition of “romantic” in Persian literature. The beauty in romance lies in its inevitable tragic ending. What’s worth giving your life for is what you can’t have. For those who are interested in learning more about this topic, IRANIAN CULTURE --- A Persianist View by Dr. Michael Hillmann (University Press of America, 1991) is a great source.

Q: In the novel’s original version, the narrator was never given a name. Why was that your first choice and why did you change your mind and call him Pasha?

MS: Well, the narrator is me, and those who know me will immediately recognize him as me. But I didn’t want to give him my name. So I left him nameless, and I was getting away with it until you, my wonderful editor, convinced me that it’s time for him and me to decouple, to go our separate ways, and to live separate lives. Then I couldn’t find a name for him. Eventually I chose Pasha Shahed. Pasha would have been my first name if Mahbod wasn’t chosen, and Shahed is my father’s pseudonym, and also my mother’s maiden name. My father is a Sufi poet who has published three books of poetry in Iran.

Q: In so many ways, the characters and events of the novel remind me of what is universal in the human experience --- the essential support offered by caring friends and family, the power of humor to see us through tough times, the clever and not-so-clever ways in which people submit to, and resist, political repression, the desire to love and be loved. Yet Zari’s horrific choice, and the characters’ extravagant response to grief, may both seem very foreign to Western readers. Can you help put those acts in a context for us that might help us to understand them?

MS: Yes, love, hate, humor, friendships are universal qualities shared by people of all nations. You’re also right in that our cultures influence the ways in which we may respond to situations. In my nonwriting life, I teach a course called “Understanding Personal and Cultural Differences.” Persians, and Middle Easterners in general, live in what the experts call “Affective” cultures. These are cultures in which people freely show their emotions, especially in times of mourning. Americans, the British, and the Germans live in “Neutral” cultures. In these cultures people don’t demonstrate their feelings; they keep them tightly under control. So, for example, the experience of attending a funeral in the U.S. would be very different from attending one in Iran. The Neutral people would come across as cold and unfeeling to the people in the Affective cultures, and conversely the Neutral people would see the Affective people as too emotional and overly expressive.

As for Zari’s “horrific choice,” I’d rather not give too much of the story away by commenting on it, except to say that what she does is not a common practice in Iran. It does occur, but rarely. She deliberately chooses such an extreme act to make a powerful statement.

Q: Do you plan to write another novel? Do you know yet what it will be about?

MS: I’m already halfway through the second book. It’s about a man who has four wives but feels he has been deprived of love all his life! I don’t have a title for it yet. And someday, I’m not at all sure when, I will certainly write a sequel to ROOFTOPS OF TEHRAN. I just need some time away from it for now.

© Copyright 2009, Mahbod Seraji. All rights reserved.

• Click here now to buy this book from Amazon.