Carry On: The Kevin C. Pyle Interview

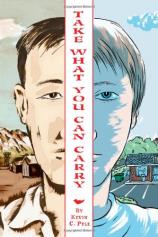

Two disparate tales, set decades apart, converge in Kevin C. Pyle’s sweetly compelling and movingTake What You Can Carry. The creator of the book shared his insights into the story with us.

What inspired the dual storylines of Take What You Can Carry?

The contemporary story comes out of my own experience working for an Asian-American storeowner. I was caught shoplifting from him as an adolescent. It was something that changed me at a critical time, and I’ve often thought of fictionalizing the experience. I think there’s a tendency to think that bad kids will always be that way instead of trying to understand why they might make bad decisions. Years ago I illustrated an article for a law journal about the success of “restorative justice” with juveniles. It’s an approach where offenders meet and listen to their victims and acknowledge the harm they’ve done. Part of the idea is that it meets the needs of the victims, and they take a role in the process. It struck me at the time how similar this was to my experience, which had the desired effect of me never stealing again. I have always wondered why the storeowner chose this arrangement instead of pressing charges. When I started thinking about translating this experience into fiction, the internment story just sort of came to me. I’ve also been interested in that history as Farewell to Manzanar, a memoir of an interned Japanese American girl, was one of the assigned books I remember really liking in high school. When I hit on the idea of the storeowner having a deep need to relay his experience and how that experience influenced his own approach to a similar situation, I knew this was a story I wanted to tell. From a technical aspect, it seemed that the alternating story line was the only way I could orchestrate the plot details in order to reveal the shop owner’s motivation at the end. Plus, I was excited by the challenge. I’m really attracted to the idea of formal experimentation in comics in general, but especially if it’s in service of the narrative, like in this story.

You dramatically alter your artistic style for the two stories. Was that difficult to pull off?

In many ways the textural inking style in the internment story is a return to a style that I worked in for many years as an illustrator and extensively in my docu-comic Lab U.S.A. It works better for larger, single images, and when I did my first graphic novel, Blindspot, I dialed it back a bit in the interest of clarity and to see if I could use it sparingly for emotional effect. But it seemed to fit with the historical section of this story because it has a decayed, emotional quality to it. I added the watercolor tones, which was new for me, and chose the sepia color to push it more into that historical feel. So the modern-day story is rendered in cleaner lines and is more spare to take that contrast a little further. It seemed to reflect a bit of the spare, clean feel of a modern suburb and convenience store.

What made you want to write about the Japanese-American internment camps of World War II?

This history has always interested me, maybe because it’s one of those clear instances where the constitutional rights that we have were just thrown out the window when deemed necessary. Artistically, when the idea first came to me, I was excited about exploring how the place itself reflects the emotions of the character—his isolation and vulnerability—and how his behavior is influenced by the setting. While I haven’t been directly affected by the Japanese-American internment, the story did end up intersecting my life in an interesting way. While I found references to “social breakdown” in the camps, I was having trouble finding actual instances of petty theft, which was important because I didn’t want to misrepresent anything. Then I remembered that a painting teacher I had in college, Roger Shimomura, had been interned as an infant and had done lots of work around that legacy. I contacted him, and he was able to confirm that petty theft was a reality and pointed me toward a book that provided many details. I ended up using one of the specific incidents mentioned, where the boys steal fresh fruit that only the hospital staff had access to. The best part of all this was that I was able to send him the book and be reassured that I had treated the subject respectfully and accurately.

The internment camp storyline is largely wordless. Did that create a particular challenge for you while working on this book?

I think the choice to tell that story wordlessly was a response to some challenges I encountered working on it. I found that I wasn’t entirely comfortable putting words in the mouth of someone whose cultural and historical time was so different than mine. Despite reading several diaries written by internees, the experience of being Japanese-American in the 1940s and then having your whole way of life taken away from you seemed so emotionally and culturally complicated that I was afraid I would get something wrong. By making it wordless, I think it gives the reader the opportunity to bring their own emotions and empathy to it rather than having me give it a particular voice. But I was also looking for a way to make that story feel like a memory, and being wordless somehow had that effect. I think it demands a certain amount of close “reading” in order to get exactly what’s happening. In some ways the historical notes help with that, and I think it would be great if people revisited the book after reading the notes. I know many people tend to reread graphic novels more than prose books, and I think they will be rewarded if they do that with this book.

Why set the book near Chicago?

That’s where I was living when I had the experience that makes up the autobiographical portion of the story, but it really could have been in any suburb. Because the internment story takes place in a specific location it seemed odd to set the contemporary story inAnytown, U.S.A.

A lot of your work has touched on issues of race and racism. Why is that important for you to communicate in your work?

I’m not really sure. It may be that I’ve spent many years doing nonfiction comics about abuse of power and authority, and in America those issues often intersect with issues of race. With Lab U.S.A. it was the weird, unbelievable, and secret nature of the history that attracted me and made me angry enough to do that book. There’s no way to tell that history without touching on race. A fair amount of that history also took place in prisons, which led in part to me doing a comic book, Prison Town, for an activist group. A few friends have pointed out how this book is also about captivity and how my nonfiction comics about prison may have grown out of the experience that drives this story. The story starts out with a scene where the angry dad of the main character has the police officer let the kids sit in jail for a few hours. That’s exactly what my dad did and it was a powerful experience for a 13-year-old. And it isn’t lost on me that my experience might have been quite a bit different if I came from a different racial and socio-economic background.

What are you working on next?

I’m currently working with the comics writer Scott Cunningham on a nonfiction book also to be published by Henry Holt. It’s about the history of parental fears and moral panics around stuff that kids love—things like the comic burnings in the Fifties, banned books, videogames, playground safety, etc. It’s a fascinating history that goes all the way back to Plato warning about kids reading fairy tales. The book shows how this hysteria is often cyclical, returning with each technological advance or particular phenomenon that captures kids’ attentions. It also functions as a way to teach kids critical thinking and be aware of their rights. It’s called Bad for You: The Truth Behind the Campaign Against Fun. I just finished the sketches and am starting to ink it next week.