Interview: February 6, 2004

February 6, 2004

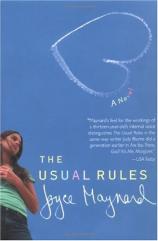

Jesse Kornbluth and Carol Fitzgerald, co-Founders of Bookreporter.com interviewed Joyce Maynard, author of THE USUAL RULES. Read on to learn why Maynard used 9/11 as the backdrop for her story, as well as why writing this book had such a personal impact on her. See why THE USUAL RULES is a great discussion book for book clubs (and the books that Maynard suggests pairing it with), as well as how Wendy, the teen protagonist has had an impact on younger readers.

BRC: Wendy's mom died in the World Trade Center, but it has been said that her dying anywhere else and in another way might have been equally effective as a way to evoke the feeling of loss. Why was it necessary for you to have the events of 9/11 as the backdrop to the story?

JM: I was in New York City on the day of the Trade Center attack --- on a visit with my older son, who attends university in the city. At the time of the tragedy, I was in the middle of a totally different novel, but having lived through the events of that day --- and believing as I do that the best stories always come out of the deepest feeling and most intensely experience emotions --- I knew, walking around the city that first night, that I would never finish that other novel. I didn't know yet what I would write instead, but understood that whatever it was, my new book would have to address the concerns of that particular moment --- namely, crushing loss and despair, and the question of where, in the aftermath of so much of those things, we might retrieve a sense of hopefulness.

I never speak of THE USUAL RULES as a novel about 9/11, and it's certainly true that I could have written about a girl who lost her mother in any of a dozen other tragic ways, instead. But the unique aspect to this particular loss lay not only in its suddenness --- and the terrible, random way it struck --- but also, in the scale of the disaster, and the experience of inhabiting not only a space of personal grief, but a whole landscape transformed by it. That made Wendy's departure from New York, and the move to California, all the more powerful, I hope.

BRC: THE USUAL RULES is filled much emotion about loss --- and growing after feeling a loss. In your afterward you explain that you wrote this book after your last child graduated college and left the house. Clearly this was written at the ending of one chapter of your life --- a time of raising children. Was this very much on your mind as you wrote, or was it more subconscious?

JM: As much as I was thinking about 9/11, as I wrote this novel, I was thinking about the fact that for the first time in over twenty years, I had no child at home. One of my sons was traveling in Africa, one was at school in New York (as men in anthrax-protection suits walked the streets around his school) --- and my daughter was doing social work in a very remote part of the Dominican Republic. What I saw, with painful clarity, was that after so many years of watching over my kids, holding their hands, trying to shield them from pain, there was no protecting them. They had only their own strength to see them through. (And the love of their family, and their love of each other.) And when you come down to it, that is the best thing to have, isn't it?

I'll tell you one more thing about the role my children's absence played in writing THE USUAL RULES. One of the things I love about writing fiction is the way it allows me to spend time with characters I care about. I can summon, to the page, the people I'd like to hang around with me for a while, and that year I decided I'd like a five-year-old boy around. (A boy very much like my son Charlie, at that age --- a thumb-sucking lover of costumes, and fantasy, with an older sister he adores, who adores him back. Out of that impulse came my favorite character in the novel the little boy, Louie.

BRC: You use the word "keen" to describe the quality of mourning and from your definition of this one word, readers see so much. Have you ever keened over an event in your own life?

JM: You are asking that question of a woman who has lived through the deaths of her parents (and, a different kind of death, the end of my marriage). I know a thing or two about keening. I think most of us have done that. We just don't always use the word for it. And it's such a good word.

(Also, I used to live in Keene, NH. Which is, by the way, a very keen town.)

BRC: While the events of 9/11 touched families and friends of victims more closely, there was sense of loss and foreboding that enveloped people across the country that day. In your recollection is there any time in your lifetime where the sense of loss was this strong?

JM: The day my mother died --- the same month my former husband and I separated, when I was age 35 ---- I stood outside in the dark and wondered if I could ever again know happiness. But of course, I have known a great deal of it in the fourteen years since that day. And it is out my optimism that a person can survive terrible loss that I chose to write this novel.

BRC: Did you feel you were in forbidden territory? Or, put another way, how hard was the book to write?

JM: Oh gosh. I have entered forbidden territory with nearly every book I've written. I think it's part of the job of a writer to study, and explore, and then give words to the forbidden subjects, the scenes we all know exist, but have trouble talking about. The thoughts Wendy has, about the bones of her mother, in the rubble at Ground Zero, are ones that numbers of family members of people who have died, who have read this book have told me they considered, as well. The tragic, terrible thing is not that I write about these events. It is that they happened, in the first place. If it's too much for a person to read what I write, she or he probably will avoid my work. But I think, for many, it serves as some kind of confirmation and reassurance, to see one's terrors named. I know I wish that in my family, growing up, we have been able to talk about what represented the source of my greatest sadness: my father's drinking. Sometimes what is worse, I believe, is silence.

BRC: You are a divorced mother of three kids. The mother in your novel is divorced and has two kids. How much did you take from your own experience?

JM: A lot. My own daughter, Audrey, is now 26 years old, but the kinds of battles Wendy and her mother go through in the novel are very much like those Audrey and I experienced when she was thirteen. It was a good (though sometimes painful) lesson, revisiting those struggles, but this time, from the point of view of the daughter, rather than the mother. I developed a much great understanding, in the process, of what it is to be a child of divorced parents. I wish I'd done that sooner.

BRC: You did prodigious research for this book. What was it like to talk to Tara Feinberg --- daughter of a fireman who died in the WTC? What was the best question you asked? What were the questions you just couldn't ask?

JM: There is no question I refrained from asking. I remember thinking, when we spoke, that this was a young woman who longed to talk about what had happened to her and her family. People had been avoiding the subject, with her. I just tried hard to convey that if something was too painful to talk about, she would tell me. She never did.

BRC: Losing a parent matures a person at any age. Losing a parent as a teenager may be harder than at any other time because a person that age is just beginning to recognize and develop his or her own sense of self. You were able to write Wendy so well. Were there memories of your own teen years that crept in here? If so, what were they? Is life for a teenager today that different from when you were a teen?

JM: I think one of the jobs of a teenager (maybe the most important job) is to separate from her parents. I was so heavily invested in pleasing mine that I did not do battle with them, as I should have, when I was Wendy's age --- and that left me with a lot of unfinished business (particularly with my mother) in my thirties. Wendy and her mother are doing something pretty healthy, in putting their anger with each other out on the table as they do (along with a great deal of love). The problem (and it is a huge one) is that unlike most mothers and daughters who fight this way and then move on to the next stage....they never go the chance to make their peace as they would have, because of the mother's death. And so it falls to Wendy to make her peace, on her own. Which she does, I believe.

BRC: Were any of these characters more difficult for you to write than others?

JM: I have to say, I loved creating every one of these enormously different characters, from the autistic boy to the teenage mother to the born-again Christian, re-meeting the mother who gave him up for adoption twenty years before. I loved putting myself into the skin of every one of them.

BRC: Often an author will reference a book's title just one time in the text. You used the phrase "the usual rules" more than once. Did you develop the title before you wrote the book, or was it a natural after you started writing?

JM: I am usually terrible at thinking up titles, and once struggled right up to the last day to choose a title. This time --- although I didn't know the title as I was writing it --- it just came to me. The usual rules...do not apply. (In unusual circumstances.)

BRC: The box of gifts that Wendy's mom left for her told so much about the story of their relationship. Wendy held off opening it. Had she opened it sooner, would it have had as much meaning? Or did delaying this give her a chance to grow on her own?

JM: Interesting question! Sometimes, I think, a gift is too precious to open for a while. Several years ago, I was interviewing a young girl in Africa. whose mother had died of AIDS. Her mother had left her a book about her life that she wrote while she was dying. The girl kept it by her bed. But she hadn't opened it yet. Maybe I was thinking about her. And more than that, about the way that opened gift from a person who has died serves to keep them alive in a small way. After my mother's death, I cleaned out her kitchen and brought home with me (on the plane) a dozen jars of chutney she had canned. I saved them for special occasions, and it took our family a few years to get through them. When we got to the bottom of the last jar, I wept.

BRC: This is book that has many great lines (I dog-eared many pages), all of which warrant a discussion, but this one thought from Josh was so dead on. "I'm not sure which is harder....When you feel like you can't go on any more, or when you start to realize you will." You ended the book before the first anniversary of 9/11, a time when many people were faced with a challenge of moving on, but realized that they still were not ready. Did you choose that timeframe for THE USUAL RULES, or did the story just tell itself that way?

JM: I actually jumped ahead in time for the book's ending, since I finished writing it before the date that Wendy was experiencing. I wanted to bring Wendy out of the woods, metaphorically speaking, to a place of hopefulness and healing. (Knowing, as I did, that her pain will endure forever.) In real life, the arc she travels over the course of the novel would probably take a lot longer than the span of time covered in THE USUAL RULES. But I wanted to leave the reader with a sense of hope. And because I had come to care for her so much, I think I wanted to get her home and back with her brother, as soon as I could --- but not before she she'd gotten what she needed to, in California. I guess you could say I felt pretty motherly towards this girl.

BRC: In 1972 when you were eighteen a New York Times magazine piece positioned you as a spokesperson for your generation. The picture and title couldn't have been more attention-getting: A teenager looks back on her life. What did that piece do for you as a writer?

JM: The best and the worst. Professionally, that article launched my career. It also ended --- prematurely --- my youth. It led to my leaving college, embarking on a fairly destructive relationship, and cut short the natural development of a young writer (which should include some years of not publishing one's work, I believe now.) I don't spend a lot of time on regrets, but I wouldn't wish that experience on a child of mind, or any young person who came to me for advice as a writer. You can read all about it in my memoir, AT HOME IN THE WORLD, of course.

BRC: You wrote this book in Guatemala. What was it like to conjure a great urban tragedy --- and its effects --- in such a remote place?

JM: Yes, for the entire time I was writing THE USUAL RULES, I lived in a little rented house on the shores of Lake Atitlan --- a tiny Mayan village in Guatemala. I spent my writing day looking out at the water, and a volcano. I think that was the perfect spot to be. For me, at least, the process of writing a novel requires a stage of taking in a great deal of information, imagery, and experiences...and then, when I am ready to write, a period of isolation, quiet, solitude and distance from my world. I found that in Guatemala --- and I still do.

BRC: Do you have any thoughts on what would be an appropriate 9/11 memorial in NYC?

JM: Well, nobody's asking me. But I always feel our culture doesn't listen nearly enough to children. I'd spend a lot of time asking them.

BRC: Can you share some stories that you have heard from readers about THE USUAL RULES?

JM: Where to begin? I think I'll just tell you that my favorite readers are the young ones, who so enter the world of my story that they forget it's a novel, and they write to ask me how Wendy is doing now. And I tell them...she's going to be okay. (Not the same as before, of course, but strong and confident and able to lead a life her mother would have wanted for her.)

BRC: Would you recommend that discussion groups read and parallel THE DIARY OF ANNE FRANK with THE USUAL RULES? Also, would it be helpful for groups to read THE MEMBER OF THE WEDDING along with THE USUAL RULES? Any thoughts on how to handle this?

JM: I think my novel would be a great selection for a book group, and would love to see readers combine the experience of reading my novel with a look at some of the novels my character, Wendy, reads and thinks about over the course of the story --- particularly the two you just mentioned. Any exercise that get people reading ANNE FRANK'S DIARY (one of my all-time favorite books) and MEMBER OF THE WEDDING is, in my opnion, a great idea.

BRC: While many writers embrace their characters as you write them, it seems this was a very personal book for you. Did you have trouble moving away from this story?

JM: There's always a certain sadness for me, which I finish a novel. The good part is, I always know I'll be inventing new characters, and falling in love with those, soon. It's a little like coming home from a trip. You have to leave that country you loved. But you know you'll visit other wonderful places, too.

BRC: What are you working on now?

JM: I've just finished the first draft of a new young adult novel, inspired by the true experience of my boyfriend, Ken, when he was a young boy, growing up on a farm in the prairies of Canada. His father shot himself, when Ken was thirteen --- thought he did not succeed in killing himself, only blinding himself. The novel --- written with the young adult audience in mind --- is an exploration of a theme that has been centrally important to me all my writing life: family silences, and the damage they do. For now, at least, I call my new book THE CLOUD CHAMBER.