Interview: July 25, 2024

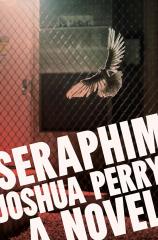

SERAPHIM, former New Orleans public defender Joshua Perry’s debut novel, is a gritty and thrilling interrogation of crime, violence and the limits of justice in the chaotic times after Hurricane Katrina. In this interview conducted by Michael Barson, Senior Publicity Executive at Melville House, Perry talks about his decision to write a work of fiction featuring a public defender as the main character and mentions two novels that served as models for the book. He also looks back on his legal career and explains what he misses (and doesn’t miss) about being a public defender.

Question: At what point in the course of your distinguished legal career did you decide you wanted to try your hand at writing a novel with a public defender as the protagonist?

Joshua Perry: Good litigators are storytellers. That’s the part of the job I’ve always loved, because I’ve always been lucky enough to represent people and causes I care about. That’s been true whether I’m in a New Orleans courtroom representing boys accused of shooting at a Mardi Gras parade, or at the U.S. Supreme Court explaining why Connecticut needs to be able to vaccinate its residents.

But the stories we tell in court belong to our clients. Especially in criminal cases, and especially with children: you meet your clients in their most difficult hour, and they talk to you about the worst thing that has ever happened to them. You owe them loyalty and privacy. True crime would have been an unthinkable genre to work in.

During the COVID lockdown, I finally had time and distance to reflect on my decade in New Orleans. And fiction was the only way to tell the truth about my clients and the work I did for them.

Q: Can you name two or three novels with courtroom settings that influenced your approach to writing SERAPHIM?

JP: During the 10 years I served a public defender, I read almost no fiction. I watched almost no movies or TV. I had no mental or emotional room. It felt too close, or too irrelevant.

I still don’t read much fiction about crime or law. Legal thrillers are difficult for me. I go to court myself, and I don’t think it’s thrilling. I think, and I’ve always thought, that it’s terrifying. We use the formalized language of law to cover it up, but court is the closest civilian society comes to the unconcealed exercise of power.

Still, of course, I have models. I read PRESUMED INNOCENT before law school and (like everyone else) loved it for its surprising but believable plotting and moral complexity. After starting my practice, though, what I came to appreciate most is Scott Turow’s refusal to make his ministers of justice --- prosecutors, police --- into heroes.

My favorite novel about trial and justice is Herman Melville’s BILLY BUDD. I’m not that interested in whether or not it gets the procedure of a court martial right. What it gets painfully right is the constraint that law puts on moral justice.

Q: You provide so many fascinating details about the process involved in serving as a public defender. There is so much strategy and gamesmanship. What do you feel is a detail that often gets overlooked in novels that share such a setting?

JP: The central case in SERAPHIM never goes to trial, and we rarely actually see Ben Alder in court. That’s true to life: trial almost never happens --- 98% of cases end with pleas or dismissal. They are so rare that most cases get resolved in the shadow of prosecutorial whim --- or, for good prosecutors, discretion --- not in the shadow of trial.

Defense cases are mostly won or lost in investigation. I don’t think most people --- including most defenders --- know much about investigation. Defense investigation is patience and empathy. Defenders can’t break down your door or drag you down to the stationhouse for questioning. They get information when they’re persistent, clever and kind.

SERAPHIM spends a lot of time in the streets of New Orleans, with Ben and his partner, Boris. That’s how the reader gets to know the city and its people. It’s also how I got to know New Orleans: presenting myself in strangers’ living rooms, in all my whiteness and Jewishness and weirdness, and asking to know the truth.

Q: When applying your own considerable experiences as a public defender in New Orleans during the previous decade, were there any references to actual cases you tried that you ultimately decided not to utilize in your plotting of the story?

JP: When I was working through early drafts, I wrote out lots of scenes that I remembered from my practice, as best I remembered them. Then I scrubbed them out of the manuscript. The stories themselves aren’t mine to tell. But what I wanted to keep was the feeling of the half-full city and the overflowing jail; the shame of letting my clients down; the chest constriction when a judge takes the bench; the wonder at the unexpected decency that came out so often --- from my clients, their families, witnesses, jurors.

Q: Now that your legal career has moved in another direction, what part of serving as a public defender do you look back on most fondly? And what element of that job do you miss the least?

JP: I miss my kids and my colleagues.

The children I worked for were exactly as good and bad as every other kid, everywhere. They were angry, loving, cynical, strong, scornful, serious. Some of them had done terrible things; more often, terrible things had been done to them. I didn’t love all of them. But I was honored to work for them. I hope SERAPHIM captures the horror of inflicting the criminal legal system on those children, who’ve gotten so much less from us adults than they need.

I had a small group of lawyers who started with me and remained my best friends throughout. They made it tolerable to go into court every day to push back against cruelty and stupidity and deceit. Ben and Boris’ relationship in SERAPHIM reflects some of my nostalgia for that camaraderie.

There are lots of things I don’t miss, but they’re all inextricably paired with things that I do.

When an accused person pleads guilty, they have to go through a process where they acknowledge giving up their rights. Yes, I know I could have gone to trial. Yes, I’m giving that up willingly. Towards the end of the list of things they’re going to live without --- a list that could have been almost endless for some of my clients --- the judge would ask: You went over this with your lawyer? And are you satisfied with the representation you got from Mr. Perry? The point of the question is to lock them in. The court doesn’t want them coming back, a week or 10 years later, and trying to rescind the plea because their incompetent lawyer didn’t explain what it all meant.

They always answered Yes, your honor, I’m satisfied. Hundreds of them said that. I’m grateful I got to serve my clients and stand next to them in court. But I don’t miss helping them fill out those forms and standing next to them when they gave that answer. They shouldn’t have been.

Q: Do you consider any one film to be the platinum standard for courtroom dramas? And if SERAPHIM were to be given the screen treatment, would you want to be given the screenwriting duties?

JP: I’d want to be given a huge bucket of popcorn and a seat by the door in case the audience hated it. But not screenwriting duties. I hope they’d hire a professional for that.

There are lots of great courtroom dramas, but my honest answer is My Cousin Vinny. The outcomes in criminal court cases are profoundly serious --- literal life-and-death stuff. But so much of the day-to-day is deeply absurd --- a clash of egos, mediated by incompetence and outright weirdness. My Cousin Vinny captures that weirdness perfectly.