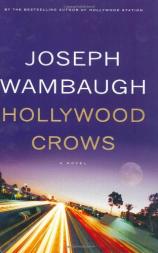

Author Talk: March 28, 2008

March 28, 2008

In this interview, former police officer turned author and screenwriter Joseph Wambaugh --- whose latest book is HOLLYWOOD CROWS, a follow-up to 2006’s HOLLYWOOD STATION --- discusses the inspiration behind many of his characters and shares what he has found to be an unlikely but effective method for editing manuscripts. He also describes the changes he has witnessed over the last several decades in both law enforcement and the publishing industry, and recounts some of his experiences working in film and television.

Question: The big story in yesterday’s Los Angeles Times was that crime is down in L.A., but the murder rate is up 35%. Why do you think this is?

Joseph Wambaugh: Always be careful of stats. L.A. is very much plagued by well-armed gangs and that drives the murder rate.

Q: Your recent novels seem to suggest that cops have to push too much paper and it prevents them from actually being police officers. Do you propose a solution to such a paper chase?

JW: Yes, a solution would be for the federal judge overseeing the LAPD "consent decree" to end it and get a life.

Q: Seeing how closely police officers’ actions are scrutinized these days, especially within the LAPD, would you want to be a cop today?

JW: I would still want to be a cop because, as the Oracle said to the troops in HOLLYWOOD STATION, "Doing good police work is the most fun you will ever have in your entire lives."

Q: There’s a chance the U.S. will elect a woman for president. Do you think a woman would make a good police chief?

JW: There are women police chiefs in many cities and there is no reason that L.A. shouldn't have one.

Q: You’ve had bestselling novels in four different decades. How has publishing changed? Has it lost or gained anything?

JW: Publishing used to be a more intimate enterprise engaged in by people who loved books and respected authors. Back in the day, they would actually publish a lot of books that deserved to be read even though the books were sure to lose money. Now publishing is controlled by a few huge conglomerates and the bottom line is bucks.

Q: Any regrets with any of your novels or television and film projects?

JW: I never go back and read my books because I am super self-critical and would find too many things I wish I'd done better. My TV and film work was pretty good, but nobody should think that screenwriters are in control of the product.

Q: Any film or TV plans underway for HOLLYWOOD CROWS since the writers strike ended?

JW: HOLLYWOOD CROWS and HOLLYWOOD STATION are being looked at by TV and feature producers but nothing is settled as yet.

Q: What’s something you wish journalists would ask you about yourself or your work?

JW: I wish that journalists would ask specific questions about the work, but of course, 90% of them are too busy to actually read the books.

Q: What’s the question you’re most tired of answering?

JW: I'm tired of answering how the LAPD felt about my first book. That was eons ago. Get over it.

Q: I read in the introduction Michael Connelly wrote for the soon-to-be reissued mass market editions of THE BLUE KNIGHT and THE NEW CENTURIONS that you wrote your first book on a manual typewriter. Do you still have that typewriter?

JW: I no longer have my little Royal portable typewriter. I used to make carbon copies. I know, what's a carbon copy?

Q: In addition to writing novels, you've also worked on a number of films. Which medium do you prefer and what is the difference between writing for film and writing a novel?

JW: Of course, no writer on the planet would be writing movies or TV episodes if a successful novel was a safe bet for the writer. The author controls the book. In TV and movies, everyone, it seems, has more control than the writer. I did have control over The Onion Field and The Black Marble films because my wife and I partially financed and raised the money for them. We had no studio or production entity backing us up. If we had failed we would have had the world's most expensive home movies. It was a very dumb thing to do, but somehow we got away with it. One other thought: writing a screenplay adaptation of my own novel (prior to the novel's publication) is helpful to the editing process of the novel. When a nuanced book of 430 ms. pages has to be reduced to a 110-page screenplay, the writer is forced to cut every ounce of fat, and more importantly, to get out of a scene and into another quickly. Writing a screenplay is helpful to developing a feel for pace.

Q: Los Angeles and the LAPD are obviously very important to your writing. How well do you think you need to know a place to use it as a setting in a novel?

JW: I don't need to know a place at all. I know people. I know cops. I know crime. I went to the Midlands of England to write my true crime book, THE BLOODING, the true story of the discovery of DNA "fingerprinting" and its first use in a murder investigation. I went to Philadelphia and Harrisburg to research ECHOES IN THE DARKNESS, another true crime story about a multiple murder involving school teachers. I also wrote a four-hour miniseries about that case.

Q: How do you know when a book is finished?

JW: I just have a feeling when a book is finished. The trick is, when's it's finished, stop tinkering with it. Just let it go and save the tinkering for the editing phase. And when that's finished let it go for good and don't go back to it or you'll find lots of little things you'll regret not having done better.

Q: Your characters are so rich and nuanced. How do you create them? Do you base them on specific people you have met? Or do you make notes of specific qualities in a variety of people and merge them together? Do your characters develop as you write, or do you know exactly who they are when you begin?

JW: My characters are pretty much composites of people I've met. Sometimes they're pretty close to the living people. My work is character driven, and by that I mean that once I create the characters I start narrating their story without a clear idea of where they are going. I let the characters take me there, and during the journey I get a better idea of who they are and make changes in order to accommodate them.