Interview: September 8, 2022

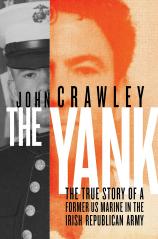

In 1975, John Crawley joined an elite US Marine unit to get the most intensive military training possible. He then joined the Irish Republican Army during the days of some of the bloodiest fighting ever in the Irish-British conflict. In THE YANK, Crawley details the grueling challenges of his Marine Corps training and how he put his hard-earned munitions and demolitions skills to use back in Ireland in service of the new Provisional IRA (known as the Provos). In this interview conducted by Michael Barson, Senior Publicity Executive at Melville House, Crawley talks about what inspired him to write a memoir about his remarkable life history, the biggest challenge he encountered as a first-time author, and his plans for a second book, which is already in the works.

Question: For how long had you been pondering the idea of turning your remarkable life history into a book? And what provided the impetus for you to finally attempt it?

John Crawley: Being a member of a secret army means that one is organically primed to keep secrets. A guerrilla learns quickly (and too often the hard way) that survival, of both the individual and the group, depends on maintaining the tightest operational security. Coming from this organizational culture writing a memoir is not the first thing that springs to mind. I pondered writing a memoir for many years. For one personal or political reason or another, the time never seemed right until now.

My principal motivation was to challenge the false narrative that the struggle for complete Irish freedom was simply about reuniting Ireland in whatever political form, even if that meant preserving constitutional divisions between pro-British Irish unionists and Irish nationalists in a unitary state. A unitary state in which the British royal family would continue to play a role in representing a minority of our citizens as some form of post-colonial garrison. Our struggle was fought to completely break the connection with England and forge a joint national citizenship based upon democracy, equality and fraternity. I wanted to explain that a so-called "New" Ireland, predicated on all the old divisions, is not what our struggle was about. I also wanted to highlight the unsung heroism of the humble patriots whose sacrifices essentially have been written out of history.

Q: Was there one memoir in particular you had read that inspired you to attempt writing your own?

JC: I have always been a deep admirer of Ernie O'Malley, who fought in the Irish War of (Partial) Independence between 1916 and 1921 and on the republican side in the Civil War in 1922 and '23. His memoir, ON ANOTHER MAN’S WOUND, is one of the best books about the Irish independence struggle during this period. O'Malley illustrates how an unforeseen event can fundamentally alter an entrenched narrative.

His light bulb moment came during the 1916 Rising in Dublin when he came close to joining his fellow University students in taking up arms against the rebels. Some inner ancestral voice caused him to hesitate. Later, while walking down O'Connell Street, he chanced upon the Proclamation of the Irish Republic pasted onto Nelson's Pillar: “On the base of the Pillar was a white poster. Gathered around were groups of men and women. Some looked at it with serious faces, others laughed and sniggered. I began to read it with a smile, but my smile ceased as I read….” O'Malley immediately took up arms against British Crown forces and became one of the Irish struggle's most influential and inspiring patriots. Reporting directly to Michael Collins during that phase of the struggle for independence, he took the republican anti-Treaty side during the Irish civil war. His memoir of the Irish civil war, THE SINGING FLAME, is as thrilling and enthralling as his earlier memoir. I could never hope to emulate his writing talent, but his example inspired me to try.

Q: Being a first-time author, what did you find to be your biggest challenge as you began writing THE YANK?

JC: My biggest challenge was figuring out what to say without incriminating myself or anyone else. The Irish Republican Army is still an illegal organization in Ireland and Britain. I hope I have managed to do that. Another challenge was simply remembering. Some of these incidents happened over 40 years ago. Having said that, many are seared into my memory and will never be forgotten. Furthermore, I had never previously written with a view toward publication and didn’t know if I had the ability to do so. As Henry Ford said, “Whether you think you can, or you think you can't --- you're right.”

Q: Your training in the United States Marines during the 1970s provided you with an expertise that often left you at loggerheads with the IRA leadership once you had joined to become a soldier for them. To what do you ascribe their counterproductive stubbornness in ignoring your professional advice?

JC: The Irish Republican Army was an all-volunteer organization staffed and officered primarily by civilians. The entire leadership of the IRA came from a civilian background. Not one of them had professional military experience. This led to a rather haphazard and ad hoc approach to military training. Especially in the use of small arms and military tactics. It sometimes struck me as the blind leading the blind. Although men did volunteer for the IRA who had served in the Irish army, the British army, the US military and even the French Foreign Legion, I found that just because someone has learned something themselves doesn't mean they have the ability or skill to teach it to others. I discovered that, in some quarters, training was not respected and often undervalued.

For example, I heard a member of the Army Council (the IRA leadership body) say, "You could train a monkey to shoot." I told him you could probably teach a monkey to point and pull, but you cannot teach him marksmanship fundamentals such as sight picture, sight alignment and trigger control. Nor can you train monkeys to move, shoot and communicate as part of a cohesive team. I firmly believe a small but influential element within the IRA command structure had a vested interest in keeping things at what became known as an "acceptable level of violence" to avoid provoking a British reaction that could jeopardize their leadership position within the movement. To keep the pot simmering, but never let it boil over. They would deny that, of course.

Q: If you had a time machine, is there one decision you made during your time as an active IRA soldier that you now wish had been different?

JC: I wish I had better political insight into the negotiations and machinations between the IRA leadership and the British government. It was held as a point of principle that we would never agree to an internal settlement on British terms, which is precisely what they did. That we would never allow the British government, who was ultimately responsible for the war in Ireland, to define the very concept of peace. Had I known any of this, I would never have joined the IRA.

Q: Having successfully written a first book about your own life, do you have an idea for a second book yet? And if so, how might you approach its writing differently from your writing regimen for THE YANK?

JC: I have a substantial outline of a novel I have been working on. It is also about the conflict between the IRA and the British, but I can be more forthcoming about certain aspects of the war as it is in fiction form based on real events. I expect to be busy with marketing and publicity with THE YANK for a month or so after its release. I then hope to spend most of my time concentrating on finishing the novel.

Q: Looking ahead, what do you see as the key changes most likely to occur over the next 20 years between Ireland and England?

JC: I see little prospect for change in the constitutional status quo in the next 20 years. In 1998, British Prime Minister Tony Blair said the British government would never be persuaders for Irish unity and that not even the youngest person alive at the inauguration of the Good Friday Agreement would live to see a united Ireland. The British exit from the European Union in January 2020 has undoubtedly destabilized the situation but not to the degree that will lead to a British rethink on their claim to jurisdiction in part of Ireland. I think British strategy will continue to be what it has been since the mid-19th century, encouraging, manipulating and co-opting as many Irish citizens as possible into becoming willing accomplices in their country's constitutional division.