Interview: September 8, 2006

September 8, 2006

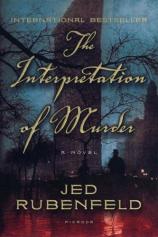

Jed Rubenfeld, a Professor of Law at Yale University, has completed his first work of fiction, THE INTERPRETATION OF MURDER, an historical novel about Sigmund Freud's 1909 visit to the United States. In this interview with Bookreporter.com's Carol Fitzgerald and Joe Hartlaub, Rubenfeld explains the real-life mystery behind this seemingly successful trip and the psychoanalyst's fascination with Shakespeare's HAMLET that plays a major role in the narrative. He also discusses how he viewed this undertaking as a departure from all things law and describes why he found writing fiction more enjoyable than his previously published Constitutional Law treatises.

Bookreporter.com: THE INTERPRETATION OF MURDER is based on an actual event --- Sigmund Freud's only visit to the United States --- though the murder mystery that is the core of the book is fictitious. What inspired you to write a book in which Freud was a principal character?

Jed Rubenfeld: Well, I'd never written a page of fiction before, so the first question is, "What made me think I could write a novel?" I'd have to say the big turning point there was the stratospheric success of my recent law book, REVOLUTION BY JUDICIARY. That book sold, I think, six copies --- four of them to members of my immediate family. When you've conquered a field that completely, there's really not much left for you to do, and you naturally start thinking about trying something new.

Seriously, it was all my wife's idea. She was the one who said I should write a novel, and she was even the one who suggested using what I knew about Freud in it.

Then I remembered something I had known about for years but hadn't focused on for a long time: the real-life mystery surrounding Freud's visit to America in 1909. Freud's trip was a tremendous success. His lectures at Clark University were attended by famous figures, such as William James. He was portrayed glowingly in American newspapers, and psychoanalysis took off in the United States. But despite all this, Freud never returned to America and later spoke of his trip here as if it had scarred him. He called Americans "savages" and "primitives." He blamed America for the breakdown of his health, even though the ailments he was referring to had afflicted him well before 1909. Freud's biographers have puzzled over this for a long time. Could something have happened to Freud during his week in Manhattan, something we still don't know about, some event that could account for his severe antipathy to America? When I remembered all this, I thought to myself --- that might make a good novel. What if Freud got involved in a case in America, a case in the sense of both a murder case and a psychoanalytic case?

BRC: Your narrative reflects meticulous research, not only of New York in the early twentieth century but also of Freud himself. Did you do your own research? How did you go about such a project?

JR: I hired a fact-checker, and I intend to blame her for all errors.

Actually, I spent innumerable hours, poring over hundreds of books and articles, reading thousands of newspaper stories. (The availability online of the historical New York Times and other old papers is a phenomenal resource; I couldn't have done the research without it.) I wanted to make the history as accurate as I possibly could, especially the details of New York City in 1909. I think readers of historical fiction today are very sophisticated and very demanding. They don't want only to be entertained. They want to be educated. They want to learn some history. In my case, that was a very good thing. The more in-depth, the more in-detail, the more real I made the history in THE INTERPRETATION OF MURDER, the better a book it became.

At the very end of the process, we really did hire a fact-checker, and she did a great job. I know there must still be some errors of historical detail, but they're totally my responsibility.

BRC: A key element of THE INTERPRETATION OF MURDER revolves around a quotation from Shakespeare's play HAMLET, specifically the enigmatic "To be or not to be..." soliloquy. Was Freud preoccupied with that quotation? Although your Dr. Stratham Younger in THE INTERPRETATION OF MURDER is a fictitious character, he gives an interesting --- and plausible --- interpretation to that immortal phrase. Is the interpretation, like the character, that of your own creation?

JR: Freud was very interested in HAMLET. He wrote about the play in his book, THE INTERPRETATION OF DREAMS (which of course the title of my book is based on) and referred to HAMLET throughout his life as an example of his theories, especially his Oedipal theories. Ernest Jones, his British follower (who also appears in my book), expanded Freud's insights into an entire scholarly article about Hamlet and then into a book. Like my protagonist, I spent a lot of time thinking about "To be or not to be" when I was younger, trying --- among other things --- to find the flaw in the Freudian, Oedipal view of the play. To my knowledge, the interpretation of "To be or not to be" that Stratham Younger comes to at the end of THE INTERPRETATION OF MURDER --- and I thank you for not giving it away! --- is original. But there's a vast literature on Shakespeare and Hamlet out there, and I'm no expert, so I can't really be sure.

BRC: One of the most memorable passages --- in a book that is full of them --- is the writing about the construction of the Manhattan Bridge. Given the importance that the bridge plays in your narrative, I am curious. What drew you to write about Manhattan Bridge?

JR: It was the Manhattan Bridge caisson --- the huge underwater chamber, far below the river surface, used to lay the bridge's foundations --- that I wanted to write about. I was looking for a memorable New York City location that wasn't a New York City cliche. As soon as I started reading about the caissons, I knew I wanted to put it in the book, because it captured the atmosphere I wanted --- darkness, uncanniness and (literally) intense pressure. The caissons were extraordinary monuments of engineering and construction, but they were also the scenes of great human suffering. (No one had heard of "the bends" before the caisson workers began falling ill from it.) As you know, the super-pressurized air in the caisson plays an important role in a very important scene in my book. Of course, the caisson is a metaphor too, but no one should ever be subjected to an author's explanation of his own metaphors.

BRC: Most authors who have a professional connection with the law --- whether they be practicing attorneys or, like yourself, a law professor and acknowledged expert on Constitutional Law --- have an inclination to write courtroom or legal thrillers. You, however, have gone in an entirely different direction with THE INTERPRETATION OF MURDER, focusing almost entirely on psychological factors as the impetus behind what is in some ways a classic "locked room" mystery. What inspired you to follow this path in your debut novel, as opposed to the more traveled one of your peers and colleagues?

JR: Well, I wrote THE INTERPRETATION OF MURDER as a way of doing something outside the law. So for me, there was never really a question. I wanted to bring to THE INTERPRETATION OF MURDER a lot of other things and other ideas --- Freud, Hamlet, the great transformations happening in New York City in 1909 --- anything but law.

BRC: While your style is unique, parts of THE INTERPRETATION OF MURDER seemed to be a very subtle homage to authors as diverse as Edgar Allan Poe, Wilkie Collins, H. G. Wells and even, at one point, Franklin W. Dixon. What authors, if any, have influenced your writing? Is there any particular genre you favor over another? And are there any authors you read solely for pleasure?

JR: Because I was writing about New York City in 1909, I got a lot of help from Edith Wharton, Henry James and E. L. Doctorow, to name just a few. (As you astutely note, I've tried to pay homage to these and other authors at several places in the text.) In the historical-thriller genre, I thought Matthew Pearl's THE DANTE CLUB was a fantastic book, which helped me a lot too; Caleb Carr's THE ALIENIST was an influence too. I'm also a huge fan of Patrick O'Brian's seafaring novels set during the Napoleonic wars; his ability to create a historical period, to bring it to life, was definitely an inspiration. Right now, I'm reading just about every novel written by Kazuo Ishiguro --- I only wish I had an eighth of his talent.

Of course, for the last several years, most of my fiction reading consisted of reading aloud to my daughters. Along with Tolkien, I thought Philip Pullman's THE GOLDEN COMPASS was brilliant.

BRC: What was your writing schedule like while you were writing THE INTERPRETATION OF MURDER? Did you continue your professorial duties while you were writing? Did you find it difficult to integrate both of your professions while you were working on it? And how long did it take you to write it, from concept to acceptance of the final manuscript?

JR: Well, the whole process seemed to fly by. It took me about two or three months to write the first, very rough draft. Then the academic year started, so I had to put it aside. Then there was about six months of rewriting before the manuscript went to publishers. That was just about one year ago today. And yes, I had to keep up with my real job as a professor the whole time.

BRC: While THE INTERPRETATION OF MURDER is your first published novel, you have previously published two treatises on United States Constitution Law as well. Which experience --- writing fiction and writing nonfiction --- did you enjoy more? What, if any, are the advantages and disadvantages of one over the other?

JR: I had more fun writing this book than anything I'd written since my very first law article. One of the things I loved about writing fiction: you can put into it any ideas you want. My interpretation of "To be or not to be," for example: if I had been writing an academic work, I could never have put that in. First of all, I'm not even in that field. Second, to write about HAMLET, I would have had to become expert in the entire literature on the play. Third, and worst of all, I would have had to marshal arguments and evidence. I would have had to try to prove I was right. But in THE INTERPRETATION OF MURDER, I was able to go right to what was most interesting --- the idea itself --- without the academic apparatus. Of course, that can be a disadvantage too. Maybe somebody else has said the same thing before, or maybe if I had read more of the literature, I would have realized I was totally wrong! (But I doubt it.)

BRC: Do you have any plans for writing another work of fiction? If so, what can you share with readers about it?

JR: I do have some have ideas, but I'm not telling anyone yet. Believe me, my publishers keep asking the same question, but I haven't told them either.