Interview: July 24, 2009

July 24, 2009

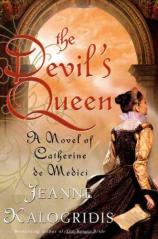

Jeanne Kalogridis's latest work of historical fiction, THE DEVIL'S QUEEN, centers on Catherine de Medici, queen consort of King Henry II of France. In this interview with Bookreporter.com's Melanie Smith, Kalogridis explains how she first became interested in this 16th-century monarch and elaborates on her attempt to shed light on the events that perhaps unfairly earned her a reputation as the ruthless schemer responsible for the St. Bartholomew's Day Massacre. She also discusses some of the fascinating cultural practices of the time she discovered through research, reveals what she found most intriguing about that period in history, and shares details about her next work in progress.

Bookreporter.com: Catherine de Medici has been labeled one of the most ruthless rulers of France, who, together with her son King Charles IX, fueled and supported the St. Bartholomew's Day Massacre of 1572. But some historians disagree with the extent of Catherine's involvement in that event. THE DEVIL'S QUEEN supports an alternate theory suggesting that her involvement was motivated not out of cruelty but from a desire to protect her family amidst an inevitable wave of violence spreading across France. What motivated your portrayal of Catherine de Medici, and how do you want readers to perceive her?

Jeanne Kalogridis: To answer the first question: While I was in the earliest stage of doing research about Catherine, I noticed that the Huguenots had thoroughly demonized her in literature and tracts, portraying her as the most evil woman in the world. The charges against her as a Machiavellia plotter who took delight in the slaughter of innocents seemed a bit extreme. Then I had the great good fortune to discover Leonie Frieda's excellent biography about Catherine, which presented a very balanced picture of what actually happened. Catherine was far from evil; in fact, she was trying to *prevent* a massacre, not cause one, but the situation spiraled out of control.

I'd like readers to see her as the complicated character she was. She endured a terrible childhood --- she was orphaned almost at birth, and at a young age, was imprisoned for three years by rebels who couldn't decide whether to kill her or let her live. My novel proposes that the insecurity that resulted from her imprisonment led her to value security and family above all else.

BRC: Many of your historical novels have common characters and points of plot. For example, I, MONA LISA is largely about the Medici family and their association with Lisa di Antonio Gherardini, while THE DEVIL'S QUEEN is also about the Medici family and in the same general timeline. The monk Savonarola, Pope Alexandar VI and King Charles are mentioned across several of your books. What motivated you to choose characters and stories that were interconnected between your novels?

JK: It flowed naturally from my research. When I began to write I, MONA LISA, I read everything I could get my hands on about the Medici...and I became fascinated by Catherine.

BRC: THE DEVIL'S QUEEN is marvelously descriptive in its history, especially with regard to character development and political maneuvering. How many hours of research went into the book, and what does your research and investigative process entail?

JK: I wouldn't be surprised if there was a 10:1 ratio between research and the actual writing. It's ridiculous, really, how much research (followed by much checking and re-checking) is involved. (In fact, I highly discourage anyone who isn't obsessed with details --- as I am --- from attempting to write a historical novel.)

I start by going online and finding as many bibliographies as I can about my subject. Then I head to a university library and check out the maximum number of books allowed, making sure not to miss out-of-print books or unusual media. I read first to get a general feel for the historical/regional background, then narrow it down to my main characters. For example, for THE DEVIL'S QUEEN, I got my hands on all available biographies on Catherine, her husband, her father-in-law, and her husband's mistress, Diane de Poitiers. It's amusing to discover how much some of these works contradict each other, depending on the slant of the writer.

The books that are the most useful I purchase, so that I can mark them up and refer to them hundreds of times during the plotting and writing of the novel.

Then I create very detailed timelines for each section of the novel, and create files of all the images of the different characters and places. And of course, I make maps of the buildings where events take place.

I'm usually checking my research up to the very last day of writing. And of course, after the book goes to the editor, we check everything again.

And there will still always be *something* that isn't right. :) When I wrote THE BORGIA BRIDE, I made the mistake of not checking an old biography of Pope Alexander, which stated that he had thrown chocolate candies down women's bodices and then made a great show of retrieving them with his lips and tongue. I took it and didn't think to check out the chocolate business. My mistake: Chocolate did not arrive on the European continent until a few years later.

BRC: Did you intend for this book to have some feminist elements? Do you feel that Catherine would have been a good leader had she been born a man?

JK: Did I intend for Catherine to be seen as a human being equal to the male characters in the book? I'd hope so; why wouldn't I? Yes, I wanted Catherine to be seen as a human being just as important as, say, her father-in-law, Francois I, or her husband, Henri. The flip side of that is, of course, that Francois and Henri are human beings, too, and therefore just as valuable as Catherine.

Catherine *was* a good leader. The French have commented that she was one of the ablest, most intelligent monarchs ever to sit on the French throne. However, it would have been a heckuva lot easier for her to get things accomplished --- and she no doubt would have been able to avert the Massacre --- had she been born male.

BRC: Some of the cultural practices described in THE DEVIL'S QUEEN are extraordinarily repulsive and shocking --- for example, the prevalence of slavery, the law of witnessing the coupling of newlyweds on their wedding night, and the instance of an infant's legs being broken to save the mother from death in childbirth (at the cost of the infant's life). Were these barbaric practices widespread and frequent, or contained to royal families and persons of great importance?

JK: Slavery was a fact of life in Renaissance Italy. As for witnessing the coupling of newly married couples: That was reserved for kings and nobles, since they usually married in order to secure political alliances. It was therefore important that witnesses verify the coupling took place. Traditionally, the highest-ranking person --- the king or duke, along with a cardinal --- was required to be the witness and to sign a document swearing that the marriage was consummated. As for the breaking of the infant's legs: that was recorded history in Catherine's case. I don't know whether it was a widespread practice.

BRC: A resounding theme of THE DEVIL'S QUEEN is that of fate as an inescapable, timeless force. Catherine's efforts to thwart her own destiny and those of her loved ones only had so much power before they faltered, and indeed she feared retribution for involving herself in the occult to try to change the outlook. Without giving away too much plot, can you elaborate on why Catherine's fate was inescapable for her?

JK: The book was written from Catherine's point of view. Although I don't believe that fate is inescapable, Catherine did. And perhaps she behaved in a way to actually bring retribution upon herself, because she believed it was coming. I *do* believe that her frenzied attempts to keep her sons on the throne --- while also struggling to avoid war with the Huguenots --- led directly to the events that spiraled out of control to become the Massacre.

BRC: THE DEVIL'S QUEEN, THE BORGIA BRIDE, I, MONA LISA and THE BURNING TIMES are all intriguing stories that hold unique fascination for readers interested in history, and all are set in Renaissance France and Italy. What interests you about 14th through 16th century France and Italy?

JK: I'd say it was THE BORGIA BRIDE, my second historical novel, that really got me hooked on the period and the area; the Borgias are so deliciously evil. The more I read about the period, the more I realized how fascinating it was: Italy was broken up into dozens of small city-states, and the political maneuvering of all the different rulers is the stuff of drama. You had constant wars, plague, a blossoming of art and culture... It's such a rich period to explore. And best of all, the Florentines were incredible record-keepers, so we can really see *exactly* how they lived their lives. I just adore it.

BRC: While Catherine is an intelligent, capable and caring woman who I could relate to in THE DEVIL'S QUEEN, it's still disturbing to think that the fate of a nation rested in the hands of a woman whose foremost concern was not for her people but protecting her own family and their power. She appeared to be drawn into the opulence and waste of the royals even after being imprisoned and starved for years, and her love for her family ultimately seemed a poor excuse for choosing personal interests over the good of hundreds of thousands. Was Catherine a product of corruption by the French court? And do you feel that THE DEVIL'S QUEEN makes a case for an inherent conflict of interest in monarchal governments?

JK: "the fate of a nation rested in the hands of a woman whose foremost concern was not for her people but protecting her own family and their power:" And that would be different from every era in history in what way? I don't mean to be cheeky, but Catherine was actually a decent monarch compared to most. Read about the Borgias; they killed even their allies for monetary gain, to fund their war which was intended to make the Pope the single earthly ruler of all Italy.

I believe that monarchies are inherently corrupt, since the family line is preserved at any cost --- and Catherine was a product of a society that worshiped the monarchy. I have no doubt that she believed that God singled her and her family out to be rulers, and that she therefore was entitled to an opulent lifestyle. Yes, there's definitely an inherent conflict of interest, and it's been going on for thousands of years.

BRC: Astrology and fortunetelling are fascinating elements in THE DEVIL'S QUEEN. I'm curious about how much weight superstition actually carried for people of the Renaissance era. How unusual was the use of astrology in those times, and were talismans and herbs socially acceptable?

JK: In Renaissance France and Italy, it was the custom for all prominent persons to have a natal chart cast soon after they were born. Most rulers had court astrologers; it was considered a science in those days, no different from astronomy. Renaissance magic, which included the use of astrology with talismans and spells, was *sometimes* considered socially acceptable --- it really depended on the current pope's attitude. Along with the rise of Protestantism, however, came a rejection of astrology and magic as evil, the work of the devil.

BRC: Where have your life travels taken you, and have you been able to personally explore any of the cities and relics you've written about?

JK: I haven't had much of a chance to travel --- but hope to soon. I'm dying to go to Italy and, of course, France.

BRC: How did you become interested in the arcane arts?

JK: Through reading and researching. I think it's all interesting if one looks at it from a psychological perspective --- as a form of self-hypnosis, say --- rather than a scientific one.

BRC: You are a highly experienced and published writer, and your writing spans many genres --- historical fiction, science fiction, horror. What is your favorite subject to write about? And are there any more Star Trek novels or movie novelizations in store for you?

JK: I adore writing historical fiction, of course, because I learn so much in the process. But I must admit that I'm drawn to vampire fiction. As for Star Trek: I've seen the new movie and I love it, but I currently have no plans to write more Trek.

BRC: Why have you chosen to use a pseudonym for some of your published works, and how did you come to choose the name J. M. Dillard?

JK: Because that's the name I was born with: Jeanne Marie Dillard. Kalogridis is my married name. When I decided to write historical fiction (which includes my vampire trilogy, The Diaries of the Family Dracul), it was a major departure from the "Dillard" style and, I realized, wouldn't necessarily appeal to Dillard's fans. So I went with Kalogridis. I've always liked exotic names, anyway. By the way, folks, it's pronounced "Kal-oh-GREED-us."

BRC: Who in your life has inspired you the most and helped you to become successful?

JK: Well, my dad helped teach me to read and saved most of my childhood attempts at writing --- I think he's hoping to use them against me someday. :) And my agent of 25 years, Russ Galen, was the one who first said to me, "Jeanne, I really think you should try your hand at a historical." I owe both of those men a lot for their support over the years.

BRC: What are you working on now, and when might readers expect to see it?

JK: I don't yet have a title that satisfies me, but I'm working on a novel about Caterina Sforza, a true warrior of the Renaissance. She was amazing and on a couple of occasions, single-handedly held off entire armies. The new novel covers the period from 1476-1500, and visits Milan, Rome and the Romagna. You'll see some more interesting "tie-ins," from a totally different perspective, to my other novels as well.

• Click here now to buy this book from Amazon.

© Copyright 1996-2011, Bookreporter.com. All rights reserved.