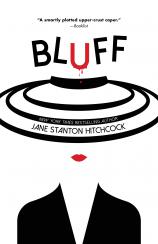

Author Talk: April 3, 2019

Jane Stanton Hitchcock is a New York Times bestselling author, playwright and screenwriter. She is also an avid poker player who competes in the World Poker Tour and the World Series of Poker. The publication of her sixth novel, BLUFF, marks her return to the world of crime fiction following a nine-year hiatus. In this interview, Hitchcock talks about the inspiration for her latest work of fiction, which pays tribute to her passion for poker; why she refers to her protagonist, Maud Warner, as a “#MeToo murderer”; her satirization of so-called “high society”; and the writers who most influenced her at the start of her career as a novelist.

Question: BLUFF grew out of your own mastery of poker. In what ways did that iconic game inspire this crafty novel?

Jane Stanton Hitchcock: First of all, I would never say I had “mastered” poker. If anything, the game is my master. It’s taught me a lot about life and how to deal with adversity --- namely, there’s no point in dwelling on bad luck or one’s mistakes. Hard as it is, you sometimes have to say “Next Hand” and get on with it. I also realized that at the poker table I was being underestimated just as I had been in life. Players never expect an older woman to play anything but Old Lady Poker --- just as the guy who swindled my mother out of millions of dollars never expected me to find out about his larceny and ultimately help put him in jail.

When I made this connection, I found a way into the book: Combine being underestimated in life as well as in poker and then write a twisty tale of murder, revenge and bluffing. Hopefully the reader will be intrigued by the characters and swept up in the twists and turns of the story. The book is one long poker hand with a Flop, a Turn and the River. As readers play the hand with me, I want them to be thinking, How the hell does she get out of this? Only one way: Bluff!

Q: “Mad Maud” Warner is a complex character --- and a timely one, given the fervor of feminism and the #MeToo movement. Do you see Maud as an everywoman of sorts?

JSH: As I say in the book, “Older women are invisible and we don’t even have to disappear.” Power derived from supposed weakness is the primary theme of BLUFF. In the very first scene, Maud is able to escape because no one can fathom that a woman like her --- an older, well-dressed socialite --- could have had the balls to commit such a shocking crime in a posh and crowded restaurant.

The book is told in two voices: Maud’s own, as she recounts what led her to commit murder, and the third person, which details the crime and its aftermath on all the people involved. My hope is that the reader will be rooting for Maud as she explains what has led her to such violence and why she thinks she can possibly get away with it if she literally plays her cards right! I guess she’s a #MeToo murderer!

Q: You also satirize high society in BLUFF. Do you view humor as a tool for enlightenment?

JSH: I like what Abba Eban said: “The upper crust is a bunch of crumbs held together by dough.” I grew up in so-called “High Society,” and, as I say in the book, “money is a matter of luck and class is a matter of character.” Maud knows she can trust some of her dicey poker-playing pals much more than the “social” friends she’s known her entire life. I also say, “Money exaggerates who people are. If you’re good you’ll be better, if you’re bad you’ll jump right down on the devil’s trampoline.” A lot of people think having money makes them better than other people. I like to aim my pen at such pretension, and there’s no better way to do it than with humor.

I’d have to be Dostoevsky to write my own family’s story without humor. As the book shows, money doesn’t save anyone from addiction, swindling and death. In fact, money often makes things worse. But there’s nothing more exasperating than self-pity. So telling my family’s story was a challenge. It took me 19 drafts! But the poker theme eventually helped me harness the humor in all the darkness.

Q: In addition to being a novelist, you are also a playwright and screenwriter. In what ways do these disciplines inform one another?

JSH: Movies are really a directors’ medium, so a writer is blessed if he/she has a good director. Enough said. Playwriting taught me about creating scenes and developing characters through dialogue. In the theater, time on the stage grows more expensive with each minute. You have to engage the audience. Therefore, you always have to ask yourself, What’s at stake? Why should people care about these characters, this situation? You have a captive audience sitting there waiting for things to develop in a finite amount of time. The novel has no such constraints. But I confess, I love a good, twisty plot. I like every scene to further the story, but I also think it’s important for the reader not to be one jump ahead of me. It’s when surprise meets inevitability that I feel I’ve done my job. I want my readers to say, “Wow, I didn’t see that coming, but now it all makes sense!”

I try to give the reader a sense of place without overloading the description. Action is character, and I really like writing dialogue, putting myself into all the characters --- the good, the bad and the ugly. It’s fun to create a good villain and more fun to see the villain get his/her comeuppance. But in my books, there is usually an anti-heroine who is, herself, operating in an amoral sphere. In BLUFF, I want my audience to be complicit in Maud’s revenge and root for her to earn it.

Q: Who were the crime authors whose books had most influenced you at the time you decided to enter the field yourself?

JSH: To be honest, I didn’t know I was entering the field when I wrote TRICK OF THE EYE. I thought of the book as literally a trompe l’oeil canvas for the readers who are led to believe they are looking at a simple whodunit when, in fact, the real picture is about a dark acquisition. I was thrilled when mystery lovers liked it, and it was nominated for both the Edgar and the Hammett Prize. I think those fans made me realize I had a mind for murder!

The writers who most influenced me at that time were Patricia Highsmith, Ruth Rendell, Edgar Allan Poe and Daphne du Maurier.

THE TALENTED MR. RIPLEY has been a favorite book of mine since I first read it and got pulled down into Highsmith's amoral rabbit hole from the very first page.

Ruth Rendell’s A JUDGEMENT IN STONE is a brilliant book. Again, dealing in the amoral and the power of ignorance.

I’ve always worshiped Poe, even though I’m claustrophobic! Poe is quite simply a genius who brilliantly concretized all the darkest fears of the human heart. He writes about the soul of a murder. His stories are fresher than ever today. Sometimes I think we are all living a version of “The Mask of the Red Death.”

Q: Having now returned to the world of crime fiction after a nine-year hiatus, did you notice any change in your writing approach versus your technique from years back?

JSH: A writer never really stops writing. During this nine-year hiatus, I was working on three books while trying to sort out a difficult family situation. As a writer, I was always used to being an observer of social life. Writing took me away from my problems.

However, with BLUFF, I’m not only an observer but a real participant in the story, which is what made it so difficult for me to write. It was painful to look back on the ruins of our family. So I would work on it, then put it away and work on the other books. I knew if I ever published BLUFF, I’d have to get the tone just right because I hate self-pity.

In writing BLUFF, I came to realize how blessed I’ve been. I remembered the words of my stepfather who always said, “Anything you can buy with money is cheap.” That lightened things up for me and made me think, Okay, humor and murder is the only way to go!

I often wish I did have a “technique” because then I might have a road map of some sort. As it is, I write until my characters take over the story. Of the three books I was working on, Maud in BLUFF took over the story in a singular way. It took me 19 drafts to get her story just right. I just hope I succeeded.