Interview: October 3, 2003

October 3, 2003

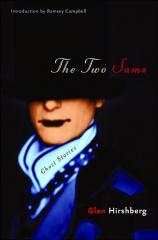

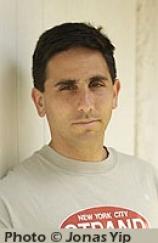

In this special Bookreporter.com interview with Wiley Saichek acclaimed author Glen Hirshberg chats about his latest book, THE TWO SAMS, and shares his writing influences and path to publication.

BRC: Your debut book, THE SNOWMAN'S CHILDREN, was a novel, while your current release, THE TWO SAMS, is a short story collection. Which format do you enjoy working in the most? Why?

GH: For a number of reasons, I have always been more comfortable working in longer formats. I value character and atmosphere heavily, and like to give my stories and the people that roam them room to develop, breathe, and surprise me. Though THE TWO SAMS is indeed a collection, four of its five pieces are actually novellas, and the fifth is a long short story.

BRC: When did you know you wanted to become a writer?

GH: I'm pretty sure this happened before I was born. The earliest existing record of my desire to be a writer is a 90-minute cassette of me, age three, following my parents and relatives around the house and telling them a sustained narrative about my vicious younger brother (age one, at the time), the things and pets he wrecked, and the ways I saved them. The funniest thing about the tape is the way relatives disappear from it, one by one, until there is only my father, forever cheerful right up until the last "Did you know what happened?" At which point there is a savage growl, and the tape slams off.

BRC: What authors do you enjoy reading? Which authors inspired you to write?

GH: I read absolutely everything, and like at least something about much of what I read, so the first question is a difficult one. I can tell you some things I have loved lately: Ann-Marie Macdonald's second consecutive astonishing, beautiful novel, THE WAY THE CROW FLIES, Mikal Gilmore's devastating memoir, SHOT IN THE HEART, Michael Ondaatje's lovely and lyrical RUNNING IN THE FAMILY, Ian Rankin's grim and brooding Rebus mysteries, and Thomas Hardy's WESSEX TALES. I also just read a wonderfully sad, eerie small press ghost story collection by Gary Braunbeck called GRAVEYARD PEOPLE.

As far as writers that influenced me, once again, there are many. I have always been mesmerized by the vivid, brooding landscapes and sense of looming fate in the early Cormac McCarthy novels. I definitely went through a phase of trying to pinpoint the sources of Ramsey Campbell's suffocating atmospheres created from parks, merry-go-rounds, everyday street-corners, etc., and I have always loved the way ghosts and monsters in his work squirm loose from people's psyches and creep in from the edges. J.P. Donleavy's tripping, stumbling prose rhythms and wonderfully sophisticated tone of giddy melancholy taught me much about loving language and aiming for emotional richness. I also love the way London keeps unfolding into endless hidden streets and shadowy corners in Arthur Machen's stories and autobiographical books. And Marilynne Robinson's astonishing evocation of childhood in Housekeeping has been something I have treasured ever since I first read it. Certainly, some of my own work strives for similar effects, in very different ways.

BRC: What story/novella from THE TWO SAMS is your favorite? Why?

GH: Honestly, they all mean different things to me, so it's hard to compare. The title story, obviously, is the most personal. "Mr. Dark's Carnival" has always been my students' favorite, and it at least strives to evoke aspects of Montana that I treasured during my time there. "Shipwreck Beach" and "Struwwelpeter" are both odes to people and places that I love and have either left or lost, although none of the characters in these stories are based on any one specific person. And "Dancing Men" remains one of the most difficult and uncomfortable pieces I have attempted-I think I was intimidated by the subject matter at first, and really had to work up to letting the story loose to go where it would-so I'm pleased with that one just because it turned out at all.

BRC: Your work can be considered "cross genre" in that it is not easily classified as one category. Did this make selling your work harder or easier? Please share your path to publication with us.

GH: In a way, I suppose the answer to this question is both. That is, I think it made my work initially hard to sell because it is not easily summarized in a one-sentence "It's like THE SHINING on anti-depressants" kind of pitch. At the same time, lack of categorization has made my work at least potentially appealing to many different sorts of readers. THE SNOWMAN'S CHILDREN, for example, was a selection of both the Literary Guild and the Mystery Guild book clubs, and was also nominated for an International Horror Guild Award.

My path to publication was odd (like everyone's, I suppose). An early draft of SNOWMAN made the rounds in 1998, garnered lots of interest, and apparently caused lots of argument, mostly about whether it was straight literary fiction or a literary thriller, at a number of houses. Meanwhile, I was trying to get going on a new novel but kept becoming distracted by suggestions for revisions to SNOWMAN. Finally, during a lull, I took a suggestion from my students and tried writing down one of the ghost stories I've been telling them every year for Halloween since I started teaching. The story ("Mr. Dark") came out over 17,000 words long, and therefore useless for publication, I assumed, as it was too long for a magazine and not long enough for a book. So of course, that was the fastest and most important sale of my career. I e-mailed it to Barbara & Christopher Roden, who run the wonderful Ash-Tree Press, not because I thought they could use it, but because I had done some reviews for them in the past and thought they could let me know whether I had anything worth working on here. They wrote back and bought the story for their Shadows and Silence anthology three hours later. Within months, that story had been selected for Ellen Datlow and Terri Windling's YEAR'S BEST FANTASY AND HORROR, short-listed for a Bram Stoker Award, and nominated for the World Fantasy Award. Suddenly, editors were asking me for more stories, and the swirl of excitement caused by "Mr. Dark" and its successors seemed to convince some of the New York publishing establishment that whatever it was I was doing, someone out there seemed to be enjoying it. I was lucky enough to land with Carroll & Graf, whose wonderful editorial staff has focused on sharpening and marketing my work, rather than funneling it in one particular direction.

BRC: What courses do you teach? As a teacher, how do your students react to your status as a published author?

GH: I have taught everything from Introduction to Fiction Writing and Composition courses at the undergraduate university level to 7th grade English. Currently, I am the Humanities Department Chair, in charge of the English and History programs, at Campbell Hall, and I also direct the creative writing program. That program is one I have built from scratch. Based around the most useful principals of a graduate school-style MFA program and meant to honor high school writing and demand more from it than traditional high school creative writing courses do, those classes have taken off and become the center of my teaching life at the moment.

I do think my students benefit from watching me go through the astonishing and sometimes just plain ridiculous ups and downs of the publishing life. But I also continue to benefit, both as a writer and a person, from the relentless, essentially intense and trusting relationships that can build between teacher and students.

BRC: In whatever genre you are working in, how do you decide how many graphic details to include in a scene? Do you worry about "going overboard" with the gore? Why or why not?

GH: My stories don't tend to be gory, so this is rarely a concern for me. I guess I feel that there should be exactly as much gore as any given story requires. If a piece of mine needs something ugly in it (like some of the Nazi reminiscences in "Dancing Men," for example), then I will put it in. As a general rule, though, gore neither interests nor scares me much on its own.

BRC: A lot of genres --- from horror to mystery to science fiction --- have a number of writer organizations. Are you involved in any organization? Do you encourage aspiring writers to look into joining such an organization or a writers' group?

GH: I belong to the Ghost Story Society (run by the Rodens, who also run Ash-Tree Press), as well as various teaching-of-writing organizations. And sure, writers should join any group where they feel they might find peers who can give them strong, useful feedback and advice. But writing is, in the end, a solitary profession, and I guess what I mostly encourage aspiring writers to do is write, constantly. The only "writer's groups" I ever belonged to were the MFA workshops at the University of Montana, and those were most useful in helping me find a small handful of people who have become ruthless (but constructive) readers of my work for many years. I even married one of them.

BRC: What do you love about your fans? Tell us about a memorable encounter with one of your readers while on tour, or via your website or email.

GH: I can tell you what I appreciate most, and that is people's willingness to read what I write and assess it for its merits, rather than whether any given piece fulfills a pre-existing set of expectations. That is, I'm so grateful that so many avid readers of horror fiction, for example, seem willing not just to read but find things to love in my pieces, which are mostly, to me, at least as sad as they are scary, and much more about living people than they are about the dead (or living dead). Similarly, I'm grateful to those readers of literary fiction who picked up SNOWMAN, despite its horrific overtones, and then took the time to write me about that book's evocation of childhood-and about its unsettling central narrative.

BRC: What can you tell readers about your current work in progress? When can we expect a new book or story to appear?

GH: I've got two projects running at the moment. I am working on a new set of people-and-their-ghosts stories, and those have already begun to trickle out. A novelette called "Flowers on Their Bridles, Hooves in the Air" appeared on SciFi.com in August, and I have a brand new ghost story that I'm polishing off. That one may make its premier aloud, as I think I may read it during my performance with Kelly Link at the Player's Club in New York on the night before Halloween in a few weeks.

I'm also hard at work on a new novel, a piece of historical literary fiction called THE BOOK OF BUNK. That book concerns the Federal Writer's Project of the 1930s, two gifted and combative twenty-something brothers, F. Scott Fitzgerald, the blues, the ghosts of the woods of the Smokey Mountains, a sword-juggling orphan who has transformed herself into a town legend, and the importance of storytelling as both an art and a way of surviving and loving the days.

I'm hoping to complete both the novel and the new collection in the coming 9 months or so, with both books perhaps appearing early in 2005.