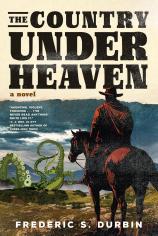

Interview: May 15, 2025

Louis L’Amour meets H.P. Lovecraft in THE COUNTRY UNDER HEAVEN, a thrilling western epic about a former Civil War soldier wracked by enigmatic visions. In this interview conducted by Michael Barson, Senior Publicity Executive at Melville House, Frederic S. Durbin talks about his extensive research for the book; the authors who have most influenced his writing; and the inspiration for his protagonist, Ovid Vesper, as well as the mysterious, supernatural force known as the Craither.

Question: Did THE COUNTRY UNDER HEAVEN pose any particular challenge in the course of writing it? If so, how did you solve it?

Frederic S. Durbin: I had to learn a lot about our country and its history. I love Ovid’s time period, so the research was fun. I feel it’s really important to bring settings to life, and Ovid travels all over the West, so I delved into studying the trees, plants, flowers, animals and geography of the various parts of the story. I wanted pictures. I needed to know blooming seasons and growing conditions. I gave Ovid a love of trees and plants so I could be specific about them. I remember such things bringing novels to life for me as a kid, so I wanted to do the same. I needed the reader to be able to see everything vividly and clearly.

I had to find out about statehood. In a given year, what was a state? What was a territory? I had to learn some things about the Civil War. There were things I needed to learn for every chapter, and quite often, my research led me to more of the story, more of the plot. I wanted to bring to life the times Ovid lived in, with historical details as accurate and real as possible. Ovid glimpses General Lee and is present when President Lincoln reads his initial Emancipation Proclamation at Antietam. Ovid is within a few feet of Billy the Kid, and I looked hard at photos of Billy the Kid to get a deep impression of what he might have felt like in person if you were near him.

Then I wanted to include the people present in the West. One regret is that I think Native Americans are not as prominent as they should be in the book. There are characters who are Black and Mexican. I’m very thankful that my publisher had a sensitivity reader on staff who helped me immensely. Our westerns have long been a white mythology, but in more recent years, storytellers are showing us the West more like it really was. A book I found especially helpful was THE THREE-CORNERED WAR: The Union, the Confederacy, and Native Peoples in the Fight for the West, by Megan Kate Nelson. There are many people’s stories in the West, and there’s a history and mythology older than the one usually told.

Q: While the book’s structure seems episodic at first, by the time we reach the book’s end, it is revealed to be very much of a piece. What did you especially need to keep in mind to accomplish that?

FSD: If you’re going to ask a reader to come with you through a novel, you’re obligated to offer up the story of a character who goes through something --- an odyssey --- and is changed by the journey. A short story is usually the tale of a moment, one flash of epiphany. But in a novel, the reader needs a character who goes through life as we go through life.

The good news for the novelist is that you don’t have to have everything figured out. You’re learning the story just as a reader will. Just follow the character, watch what happens, and write it all down. The journey and the change and the payoff will come, if you’re faithfully listening and following. More about that at the very end of this interview. There are deliberate plotters, but I’m not that kind of writer. I excavate the story; I let it show me what it is. Stories always know better than any of us human writers. They come to us and say, “I’m choosing you. I’m taking a chance on you. Are you ready to tell me? Can you keep up?” You run along after them, and you write, and you hope you don’t miss anything.

Q: The framework and setting of the story is a western, though the book soon ventures very far afield. Who most influenced your writing here among authors of westerns, either past or present?

FSD: People ask me that, and the embarrassing answer is that I haven’t really read westerns, though I desperately want to remedy that. I live not far from Zanesville, Ohio, so I need to read Zane Grey. I’ve been compared to Louis L’Amour, so I want to read him. I grew up in the small-town bookstore my parents opened, and I remember the big western sections that bookstores had in those days. Right now, I’m especially curious about the work of Victor LaValle and just bought his book, LONE WOMEN, to which my novel has been compared.

But I am a fan of western movies, so I could say that Charles Portis was a chief influence through the Coen Brothers’ rendition of his novel, TRUE GRIT. That film is a delightful study of how to tell a story well, and I’ve heard it’s faithful to the book. The old John Wayne True Grit was the very first movie my parents took me to see, and it was at a drive-in theater. All I can remember from that early childhood experience is that there was a pit of rattlesnakes, and it terrified me. But in the remake, listen to what the characters say --- the diction they use. I’m pretty sure that is the Old West. I love the old miniseries “Lonesome Dove,” so I guess I’m indebted to Larry McMurtry.

I owe it to these men to read their novels. The point is, I’ve always had a consciousness of the Old West. My dad loved it and told me stories about it, and I grew up among Midwestern farmers, who plowed the fields and watched the sky.

Q: What was the most pleasurable aspect of mixing genres the way you did in this novel? And what was the biggest challenge?

FSD: Aren’t the pleasurable aspects obvious? You get to have cowboys and shootouts and cosmic dragons and bear-witches, ghosts and other worlds all in the same book! It’s have your cake and eat it, too! The challenge, I guess, is to make it all feel plausible. When things we don’t normally experience happen in our real world, how do your characters react to it? I’ve thought about that for a long time, the element of story that I call “moving into elfland.” When characters from our world encounter something supernatural, how does the writer handle it? What tack are you going to take?

A story that resounded for me was the series “Buffy the Vampire Slayer,” which faced the same challenge. A realistic high school in Sunnydale, California: How do you handle it when the principal is devoured by supernatural dogs? How do you handle it when the school is destroyed by a titanic monster?

But then, we live in that kind of world. People see things that they can’t explain. Weird connections work out in miraculous ways. Every family has stories. Every person, no matter how pragmatic, is aware of something that just doesn’t quite compute. Life is supernatural. I heard the writer Peter Straub say, “We read and write fantasy because it’s the genre most capable of depicting life as it really is.” So I didn’t really find Ovid’s story challenging to write. I just wrote about the world we live in.

Q: Ovid is a protagonist who possesses an uncanny resilience, not to mention bravery and resourcefulness. Who would you name as his literary antecedents?

FSD: I’d say he’s cut from the same cloth as the knights errant of the Arthurian legends. He’s the lone man riding through the perilous land doing good. Those Arthur stories were deeply rooted in Christianity; the knights of the Table Round had a moral compass, and they were seeking the Holy Grail. Although he doesn’t preach, it’s his Christian faith that keeps Ovid going. He’s wandering through a shadowy, hurting land on a journey toward a better place, and he helps others to see the light of that place, too. I guess just about every classic western hero is the same, to varying degrees. Many of them have some pain in their past, and they make a difference in the present with some grit, courage and integrity.

Q: Your fearsome Craither is a wonderful creation who evolves into something rather unexpected as he comes into focus in the course of the story. Were you inspired by any other non-human creatures in the literature of the past?

FSD: There’s a fascinating story by Ambrose Bierce, delightfully titled “The Damned Thing,” in which a person is terrorized by an invisible creature. More so than horror, I’d call it an early science fiction story, because --- though we never find out what the creature is --- the tale gives a nod in the direction of science by way of explanation. It’s something that’s truly Other. There’s a somewhat similar classic story by Guy de Maupassant called “The Horla.” Apparently the title in the original French translates to something like “The Outsider, the Other, the ‘What’s-Out-There.’”

And then, of course, I grew up consuming every H.P. Lovecraft story I could get my hands on. Cthulhu has a name that’s unpronounceable by a human mouth and voice. Without giving away spoilers, in my book, let’s just say that the nature of the Craither is in keeping with an overarching theme of the book, of which we get our first hint in the title of the first chapter. That theme is repeated in pretty much every chapter of the book.

So it’s natural that the Craither reflects the theme, too. And that’s not something I planned. I didn’t set out to write a book with a theme. The story told me what its theme was, and believe it or not, I’m only just now fully realizing it. So thank you for this interview!