Interview: October 12, 2023

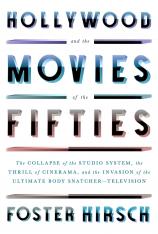

HOLLYWOOD AND THE MOVIES OF THE FIFTIES is a fascinating look at Hollywood’s most turbulent decade and the demise of the studio system --- set against the boom of the post–World War II years, the Cold War and the Atomic Age --- and the movies that reflected the seismic shifts. In this interview conducted by Michael Barson, Senior Publicity Executive at Melville House, Foster Hirsch explains why he thinks the 1950s is America’s best decade when it comes to films, talks about the impact that he believes streaming services will have on movie theaters, and names his three favorite films of the past 10 years (okay, technically just one).

Question: This is a question with no wrong answer. Do you feel that the 1950s presents a more fascinating array of film releases than any other decade? And if so, would you argue that the ’50s also was the best decade for films, when all is said and done?

Foster Hirsch: I am biased, of course, but I do feel that the 1950s is America's most vital and wide-ranging decade of filmmaking. In a fight for its survival, the industry resorted to new technologies one after the other --- Cinerama, 3-D, Cinemascope, VistaVision, Todd-AO --- and to a broader range of subject matter intended to appeal to a more diverse group of viewers. For the first time, some movies were targeted for specific age groups --- when Hollywood discovered the teenage market, which led to a range of new kinds of movies. But Hollywood still existed under the threat of the blacklist, at least for the first half of the decade. There were a number of progressive movies: revisionist westerns, political allegories, stories focused on people of color.

Also, in the 1950s, the great Alfred Hitchcock had his most creative streak, producing at least seven masterworks. Elia Kazan and Douglas Sirk, among others, did their finest work as well. To all fair-minded viewers who come to the period without a preconceived bias against the “conservative, consumerist, conformity-ridden” 1950s, the period contains a treasure trove of classics that have passed that highest and most exacting of all tests --- the test of time.

Q: In your provovative chapters on how the Cold War impacted Hollywood, you discuss how the studio heads caved in to the HUAC inquisitors with barely a shred of resistance. Why do you think they didn’t lean more on the argument that most of the pro-Soviet films they made and released between 1943 and 1945 were created at the behest of the U.S. government --- in some cases, FDR himself! --- to reinforce the idea that Russia was now our (enormously valuable) ally in fighting WWII? That might have saved so many screenwriters, actors and directors many painful hours of testifying before those various committees.

FH: The heads of studios did explain to HUAC that the wartime pro-Soviet films were made as propaganda and at the request of the government. But the claims were drowned out in the onslaught of anti-Communist feelings of the time. And the spiraling accusations of red-menace infiltration at the studios scared the moguls, many of whom were staunch Republicans who feared what at the time was considered a rising Red Menace threat. The avalanche of anti-Russian sentiment, which McCarthy took advantage of, affected the moguls, who above all wanted to protect their filmmaking factories rather than take courageous stands against the un-American inquiries of the HUAC hearings.

Q: Your delightful chapter on the career arcs of former screen queens Joan Crawford, Bette Davis and Katharine Hepburn is both profound and affecting. But I wonder if you could supply a thumbnail sketch of their feisty comrade in arms, Barbara Stanwyck, as her own storied career progressed through the 1950s?

FH: Barbara Stanwyck began to slip in the 1950s, in terms of the kinds of films that were offered to her. For the most part, she appeared in B-level genre films --- westerns and film noir primarily --- but even as her prestige was slipping, she continued to give riveting performances up until the end. She is sensational in three little-known noir thrillers --- Jeopardy, Witness to Murder and Crime of Passion --- and in an off-center western by Samuel Fuller, Forty Guns. The films represent a clear step down from her ’40s heyday. There is nothing on the same plane as her two unforgettable Oscar-nominated performances in Double Indemnity and Sorry, Wrong Number. After Forty Guns, her career was focused on television.

Q: The emergence of television in the early 1950s was perceived as a major threat to the movie studios, which, as you describe, responded with the likes of Cinerama and 3-D to make films seem more special. What is your take on the present-day dialectic between the film industry and the many platforms now offered on television?

FH: The battle between television and the film industry in the postwar decade is nothing compared to the contemporary showdown between theatrical exhibition and streaming options on television and various devices. The availability of multiple streaming devices poses a potentially mortal threat to theaters --- viewers got too comfortable during the pandemic watching films on their own. Until the present moment, the 1950s was Hollywood's most turbulent period, but the problems of today, in the post-studio era and the competition from non-theatrical viewing, are far greater. A real concern: Will theatrical distribution as we have always known it survive? Will the studios, with competition from omnivorous entities like Amazon and Netflix, survive in any fashion that we will be able to recognize?

Q: What are your three favorite films of the past 10 years?

FH: My three favorite films of the last 10 years: 1. Roma, 2. Roma, 3. Roma. For sure it is not Everything Everywhere All at Once (great title and that's it) or Barbie and Oppenheimer, bad movies for different reasons that I predict will NOT pass the test of time.