Author Talk: April 13, 2012

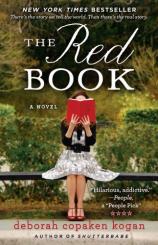

In Deborah Copaken Kogan’s new novel, THE RED BOOK, four best friends who graduated Harvard together meet again at their 20th reunion. They’ve followed each other’s lives through the university’s red book, an annual alumni publication, but the truth about each of them will come out during the course of the weekend, and they will reconnect in ways they never expected. In this interview, Kogan shares the unique evolution of her idea to write the book. She also talks about the inspiration she drew from her personal life, and discusses her passions for photography and screenwriting.

Question: On your Web site, in the piece “About the Author, Unplugged,” you touch upon the personal struggles you’ve had balancing your various careers with raising children --- something your characters in THE RED BOOK struggle with as well. What rules/guidelines/advice has helped you to navigate the multiple roles of mother/writer/spouse/friend? After your experiences, what would you tell your own daughter about leading a balanced life? (Or would you just have her read THE RED BOOK?)

Deborah Copaken Kogan: Dear lord, if I had any real, quantifiable wisdom to impart on this topic, I’d write a different kind of book on the subject altogether --- nonfiction, stuffed with studies --- both for my daughter and for my two sons. (Please, let’s not leave our sons out of this discussion.) But being as clueless about the secrets of a balanced life as the next person, I resort to well-worn platitudes --- “Sharing is caring!” --- and to fiction, where I people my book with characters who are stumbling around in the same dark as I am. What I actually tell my children, summarized, is this: The most important decision they can make in life, if they decide they want a traditional two-parent family, is to find an empathetic, loving, mature, responsible partner who is willing to share, 50/50 --- not 70/30, not 60/40 --- in the burdens and joys of both child-rearing and home maintenance.

Earning one’s own living is also, I believe, crucial in that equation, both for reasons of security (if one partner dies) and self-worth, but each partner cannot be expected to earn exactly the same as the other, especially if they work in different fields, particularly in this wretched economic climate, and certainly when one of them is breastfeeding an infant in the United States, which has pretty much the worst maternal/family benefits of any first-world country I know. (Maybe one of my pieces of advice should be “Move to Sweden.”) My husband and I try to do the best we can vis-à-vis income generation, within the professional parameters we’re given. I used to outearn him, now he outearns me, but these facts and figures probably say more about the upward trajectory of his industry (tech) and the downward trajectory of mine (media/publishing) than about how dedicated each of us is to paying equal parts of the grocery bill. In other words, thank you for buying this book. Really.

Q: You also note in your bio that male authors receive different treatment from the press than women, particularly with regard to rearing children. How have you dealt with or combated this general misperception or miscasting of your personality?

DCK: When my first book, SHUTTERBABE, came out 11 years ago, quite a few reviewers referred to me as a stay-at-home mother, even though my advance had been twice the yearly salary of my previous job, and I happened to write that particular book in an office outside my then toddler-filled home, and the fruits of my labor were more likely than not sitting on the reviewer’s desk as he was writing his review. Make no mistake: I enjoy writing books, but it’s hard work. And I say that having worked as both a war photographer and a TV producer. In fact, in many ways being a writer is the hardest job I’ve ever had. It’s lonely. It’s filled with rejection. The pay is often laughable. It requires discipline to sit down every day, cranking out words, coming up with new plots and ideas, and being willing to sit and listen to the faint rumblings of one’s imagination/muse/whatever you want to call it while simultaneously quashing that nasty, red-horned devil of internal doubts, fears, and self-criticism. But that’s not answering the question, is it? How do I combat the misperception that I’m not working when I’m working? I have no idea. I wish I did. I guess by answering questions such as these with as much forthright defensiveness as I can. Barring that, I guess I could wear a name tag that says, “Hello! My name is Deb! I’m a writer!”

On the other hand, the older I get, the less I care about the way I’m publicly perceived. I care much, much more about my quality of life, and in that sense, I feel lucky. I have work I enjoy. I make enough money to get by. I am present in my children’s lives. That’s enough.

Q: Your impetus for writing BETWEEN HERE AND APRIL was the image of a dead rat you came across while on a run in Central Park. What was the impetus for writing THE RED BOOK? Did the final draft look anything like what you’d envisioned when you first began writing the book?

DCK: The impetus for writing THE RED BOOK was sparked when I went out for drinks with Barbara Jones, the novel’s original editor, and Ellen Archer, Hyperion’s publisher. It was 2009, the beginning of the recession, and my life --- like many people’s I knew --- was in a tailspin. My husband had been out of a job for eight months. Our rent had been hiked up so high we had to move. Our older kids were entering adolescence; our then three-year-old, who’d been essentially deaf for that crucial window of language acquisition between 12 and 18 months, was having trouble speaking. Our marriage was going through painful transitions. I’d just lost my beloved 67-year-old father to pancreatic cancer before having a nervous breakdown in the middle of his book tour, which I’d promised him, on his deathbed, that I would embark upon in his stead. (He’d been working on that book, his only one, since the early seventies; he died two months short of its publication.)

I’d recently returned from my own 20th reunion, which took place in the spring of 2008, and I was telling Barbara and Ellen about both it and the red book: how the latter had always made for such fascinating reading that my husband, who did not go to Harvard, would often steal it from my bedside table to immerse himself in the lives of strangers. “It might be interesting,” I said, thinking about how different my life seemed at that moment from the version I’d composed just a year earlier, “to do a follow-up. A nonfiction book about my classmates, comparing the life they presented in the red book to the life they’re leading now, especially today, in the midst of this financial meltdown, when I bet a lot of their narratives have suddenly diverged from their previous paths.”

Suddenly, Ellen’s face lit up. “No,” she said, “not nonfiction. No one will be honest enough for nonfiction. This is a novel. And you must write it.”

“You’re right,” I said, suddenly energized. “It’s a novel.” Right then and there, I chose the class below mine --- 1989, definitely, I said, as they would bridge the abrupt transition from one economy to the next --- as well as the reunion year, 2009. A 20th reunion, I realized, would allow me to have female characters who could theoretically still get pregnant, whereas by the 25th, issues of having children, at least naturally, would be somewhat moot. Then I ordered another glass of wine and mapped out the bones of the characters.

By then I was drunk, and it was time to go home.

A month later, I’d written the first red book entries and had plotted out the weekend, some threads of which changed over the course of writing the novel, but not by much. The only real structural change was that Clover ends up with Bucky at the end; I’d planned for her to have stayed married to Danny, taking her secret of their son’s paternity with her to the grave, but something wasn’t working when I actually wrote it out that way. It was my agent, David McCormick, who said he really wanted to see the former lovers get together at the end, that it would feel right, on a number of levels; David’s usually smart about these things, so I listened to him and rewrote it.

By the time I finally typed “The End,” about a year and a half after I started, I realized that writing this book had brought me, no exaggeration, back from the dead, out of my grief, in the same way a more orthodox Jew would have gone to shul to say kaddish every morning. The daily ritual of writing about life --- which is, of course, a priori, writing about death, albeit more obliquely --- had thrust me back into the land of the living in a way I could not have imagined, when I was focused so intently on the loss of my father. I only wish he were still around to read it, and I just realized now, typing these words, that this will be the first book I’ve written that he hasn’t read.

Q: Your roles in your professional life have been as diverse as your roles in your personal life. What have you learned through your engagement in so many different fields? How much has your photography influenced your writing? Has your writing or reading life affected your eye as a photographer?

DCK: I actually don’t see writing and photography as all that different, although obviously they require different skill sets and brain hemispheres. (Don’t ask me which hemisphere goes with what, I can never remember. Google it. They know.) Each medium requires really looking, interpreting, translating human experience into something that can be shared with other humans, seeking out metaphors, preserving slices of life within an artificial, limiting framework --- in the case of photography, within a rectangle; in the case of writing, within the strictures of narrative and language. I actually think photographers would benefit from forcing themselves to write now and then, in the same way writers would benefit from running around their neighborhoods shooting Instagram photos on their cell phones.

In each medium, the key skill is knowing what to leave out. Life throws so much at us, we’re literally bombarded with images and words all day long. But it’s the job of both the writer and the photographer to filter out all that noise and say, here, look at this, look what I found, focus on what’s vital, ignore the rest.

Q: You’ve also tried dramatic writing: screenplays, a TV pilot, and the beginning of a stage play. In which kind of writing do you feel most at home? Do you imagine you’ll try essay writing, or poetry? What are you working on right now?

DCK: I feel at home in all writing, though fiction was the hardest nut to crack because of my aversion to lying. Really, I can’t even play poker because I feel physically ill if I have to pretend I have a good hand when it’s crap. I had to keep telling myself that fiction is a bunch of lies strung together in pursuit of truth, just to get through each day. I still feel somewhat squeamish about it, as if I’m doing something illicit when I write fiction, playing God with all those puppets in my head.

As for poetry, I spent the bulk of my teenage years writing it. Bad poems, mostly, but every once in a while one of them would win a student prize, which just fueled the fire of my teenage narcissism further. I once got in big trouble with my European History teacher for writing poems instead of listening to him in class, which explains why I can never remember which Mary was beheaded when or why. I was enamored of language back then, loved playing with words and sounds, and I hope my prose has retained some of that delight, as when I realized, while writing this book, that many of the songs and groups from the late ’80s rhymed: Chaka Khan, Estefan, “Too Turned On”; Simple Minds, “Red Red Wine,” “Sweet Child o’ Mine.” Oh, I can’t tell you how excited I was when I stumbled upon this. It’s the little things, really.

I am currently writing the screenplay of this book for both mercenary and educational reasons. By educational I mean that the more screenplays I write, the more I learn about the form. Or at least that’s the theory. This will be my fourth screenplay. I also wrote a teleplay. None of them have been turned into movies or TV shows. I believe it was Einstein who said the definition of insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results. What the hell did he know?

I’m also plotting out a new novel, of which I’ve written only the first line, and I have this black comedy play that’s been marinating in my head for over a year. Hopefully, I’ll get it all down on paper one day. I feel the limitations of time acutely. Writing this, for example, means I’ve spent two fewer days writing something else. And don’t even get me started on Facebook and Twitter. I actually have a program on my computer called Freedom that keeps me from going online. My friend Michael bought it for me. Thank you, Michael.

As for essays, I write them all the time. In fact, I wrote a whole book of them, HELL IS OTHER PARENTS, some of which I’ve performed live. In fact, I have one I’m supposed to be working on right now, and the laundry situation is out of control, so if you’ll excuse me…

© Copyright 2012, Deborah Copaken Kogan. All rights reserved.