Interview: May 30, 2024

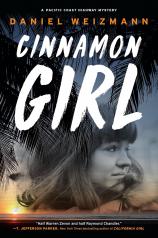

Lyft driver-turned-sleuth Adam Zantz returns in CINNAMON GIRL, a neo-noir dive into the dark side of LA’s rock scene. In this interview conducted by Michael Barson, Senior Publicity Executive at Melville House, Daniel Weizmann explains how his approach to writing this book differed from that of his debut mystery, THE LAST SONGBIRD, which kicked off the Pacific Coast Highway series. He also talks about a couple of adjustments he made to his protagonist for this second installment, the musicians who have helped influence his writing, and what readers can expect for Adam’s third adventure.

Question: How did your approach to writing CINNAMON GIRL change from your experience with THE LAST SONGBIRD?

Daniel Weizmann: Having my main character in place freed me up because I'd already learned to stop pretending to be a tough guy. Before writing THE LAST SONGBIRD, I'd been trying to write a mystery for decades. I started in earnest at 15, then again at 26, 37, etc. But I kept hitting a brick wall because my detective would inevitably be too hardboiled, too cliché. It took me a long time to just write from the POV of someone as wimpy as myself!

I also wanted to try a different kind of opening with this second one, where Adam thinks he's just doing an old family friend a quickie favor, then suddenly finds himself trapped. That's when I remembered this noodle of an idea I'd carried around for years --- a garage band test pressing as a clue.

Like many record geeks, I'm obsessed with demos, test pressings, bootlegs, small-run 45s, anything that doesn't get "officially" released or barely exists. Once I could picture Adam, this hapless Lyft driver and failed songwriter, finding a test pressing in an old trunk, the mystery started to unravel. From there, Addy led and I followed.

Q: Did you have to handle Addy differently for this second novel as opposed to his inaugural case in THE LAST SONGBIRD?

DW: I wanted him to be just one hair more confident than he was in the first book, because he's solved one crime, and now he's taking some classes toward becoming a pro investigator.

Also, in the first story he's freshly wounded from a breakup. This time I wanted him to be just strong enough to fall for someone...but maybe not strong enough to handle it well. Like all of us, his personal growth is a game of inches.

Q: THE LAST SONGBIRD looked back at the LA music scene of the ’70s. In this new book, we find the mystery centered among a group of friends who had performed together in an early ’80s garage band. What do you see as the main difference between the music of those two decades?

DW: The difference cuts to the heart of the story. The people Zantz is investigating in THE LAST SONGBIRD were real players during the "golden age" decade of rock music --- they were musicians making records with major labels, circa ’64 to ’74. Annie Linden started playing the Gashouse, which was an early folk/beatnik joint, and she ended up headlining Winterland and the Fillmore. Though Zantz meets these people in the present when they aren't quite as famous, they were there for rock's years of rapid-fire growth.

The kids in CINNAMON GIRL are just that --- kids. They only got to witness rock from the outside. By the time they became teens, rock had already been corporatized and stadiumized. Though these kids are innocent, rock music isn't. For instance, the hero John Lennon has been murdered, and their hopes for a Beatles reunion are crushed once and for all. They're the children of the aftermath.

I think the Paisley Underground was an expression of that sense of aftermath --- an obsession with mid-’60s groups like Love, the Seeds and the Byrds and a struggle to reckon with the fall of counterculture.

Q: Beyond the music elements of the plot, what else did you intend to utilize as a leitmotif in CINNAMON GIRL?

DW: The story tries to grapple with nostalgia --- my own and the culture's. Like no other time in history, we can really live in nostalgia --- the whole 20th century is at our fingertips, 24/7. And I'm as guilty as the worst. I'll binge watch Gidget killing off a box of crackers.

Connected to that, though, the story is also about fathers and sons, and their complicated exchange. Whether they intend to or not, fathers pass along their judgments, their hang-ups and their hopes for the future. And meanwhile, sons are driven by a mixed bag of forces, too --- they want to be their fathers, best them and honor them all at once. Boys want to impress their fathers in the battlefield at the same time that they war with their fathers’ spirits.

For those of us living after the golden age, nostalgia and individuation might be at odds.

Q: Both of the Pacific Coast Highway books offer a playlist of recommended music. Who are the key musicians who have influenced your writing?

DW: I use music in different ways to try to get to the heart of a scene.

When doing the writing itself, I'll play Les Baxter, Martin Denny, Nino Rota, Walter Wanderly, a few Miles Davis and Milt Jackson records, and Milt and Ray Charles’ “Cosmic Ray.” It's instrumental music that's gentle enough to stay in the background but tense enough to lure me around corners into the darkness.

Then, when a scene is in later drafts, I'll try to identify one perfect song to match a chapter. This can take several tries, but it's incredibly useful because, I think, it helps clarify the heart of the scene and identify whatever isn't credible. Once the right song gets picked, it becomes almost like a target that I aim for in subsequent drafts. And it could be anything. It could be Ruby and the Romantics, or it could be the Inflatable Boy Clams. But it's gotta be a match!

Q: Do you have any research stories you can share about things you learned in the course of writing CINNAMON GIRL?

DW: CINNAMON GIRL tries to explore the many ways teens were exploited in the ’80s. For this I had to dig into the strange world of self-actualization seminars that were big back then, the various offshoots of the Erhard Seminars Training programs, all that crazy "human potential movement" stuff. Some of those organizations were genuinely helpful to many, but some were just this side of a cult. And you gotta wonder what lessons last. It seems to me that people have to grow in real time.

Q: Are you aiming to focus on a later portion of the ’80s for Addy’s third adventure?

DW: Yes, in a way --- before, during and after the late ’80s. This time Zantz falls into the complex, magnificent world of dance, R&B, funk, hip-hop, disco, soul, urban aka Black music. He's completed his investigator's coursework, but he still needs to get his mandatory 6,000 hours in the field to go pro. Time to hustle for real!