Author Talk: June 15, 2012

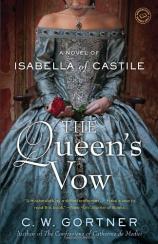

C. W. Gortner’s newest novel, THE QUEEN’S VOW, follows Isabella of Castile through her complex tumultuous rise to power and her subsequent reign. In this interview, Gortner talks about his extensive research process and the surprising and unexpected things he learned. He also discusses how he approaches writing historical fiction and reveals what he’s working on next.

Question: You are well known as a novelist who specializes in portraying controversial women in history. Why did you choose Isabella of Castile for your new novel?

C. W. Gortner: I first became entranced by Isabella while writing my first novel, THE LAST QUEEN, about her daughter, Juana. In that book, Isabella is the triumphant, middle-aged queen of legend, who has just conquered Granada and set the stage for Spain’s emergence as a modern Renaissance state. Of course, in order to depict her accurately, I researched her, but my focus was more on the woman she became after she’d won the crusade against the Moors. Nevertheless I got so many e-mails from readers telling me they’d first learned about Isabella in school because of her connection to Columbus and had fallen in love with her in my book that I realized even hundreds of years after her death, she still exerts a powerful influence. So, for THE QUEEN’S VOW I decided to explore how Isabella became the queen she was. Much of what we know about her is controversial; I was less interested in exonerating her deeds than understanding her motivations. To my surprise, I found myself captivated by her unexpected defiance and courage. She had a rather ignominious beginning as the ignored daughter of an exiled royal widow; no one expected her to become queen, let alone the sole monarch in Spain’s history to unite the country. Her love affair with Fernando of Aragón is a rarity in history, as well; she chose her husband in an era when princesses rarely, if ever, did and defied everyone to marry him, sparking a civil war. As I researched her, I realized that, as with most legends, there’s far more to Isabella than we think. She was both extraordinary and fallible, and her dramatic early years are not well known outside of academic circles. She was, in essence, a perfect choice for me.

Q: How long did it take you to write, and what special research was involved?

CWG: It took about two years to write THE QUEEN’S VOW.As with all my books, the research itself began several years before that; for the novel itself, I took several trips to Spain, including one in which I followed in Isabella’s footsteps from the magnificent alcazar in Seville to the mountain city of Granada and coveted palace of the Alhambra, site of perhaps Isabella’s most famous triumph. The alcazar of Segovia, though much transformed over the years, also carries a strong echo of Isabella’s early trials; as does the walled city of Avila and several other sites in Castile. I also read her extant correspondence and that of her contemporaries, as well as ambassadorial accounts of her and her court. Isabella has left relatively little in her own hand that reveals her inner thoughts --- she was not given to inordinate displays of her feelings --- but careful examination of what does exist, together with the aforementioned documentation and her actions during her lifetime, offer a framework from which to begin building an idea of the flesh-and-blood woman she may have been and the challenges she faced.

Q: What is one of the greatest misconceptions about Isabella of Castile?

CWG: Without doubt, it has to be the accusation that she was a fanatic who relished burning heretics. Isabella was deeply Catholic, as were most of her fellow European sovereigns. She may have been more devout in practice but it’s important to understand that persecution of religious divergence existed throughout Europe long before she arrived. The Jews, for example, had been expelled centuries before from England and France, and were barely tolerated in other countries. The suffering imposed on them and other non-Christians is a historical calamity, but not one unique to Isabella or Spain. What is unique is Isabella’s revival of the dormant Inquisition to resolve issues of non-conformity to Catholic doctrine among Spain’s vibrant and plentiful converso population (Jews who’d converted to Christianity over generations, often as a result of past persecutions). However, it’s less well known that Isabella resisted this action at first and, after she finally bowed to myriad pressures, insisted the Inquisition confine its investigations to suspected conversos only, thereby exempting practicing Jews from arrest and prosecution by her authorities. What Fernando and Isabella sought to do was utilize a time-honored mechanism of the Catholic Church to impose conformity of faith upon a people who, in truth, shared an amalgam of Christian, Jewish and Moorish beliefs, due to centuries of co-existence. Isabella’s first mistake was her belief that conversos would repent their non-conformity if only they were apprised of it; her second, more critical mistake was to trust that the Inquisition would abide by her dictates. In essence, she gave rise to a monstrous system of torture and death she could not control, even if her alleged fanaticism was in truth a sincere but misguided attempt to impose religious unity and thus safeguard her realm from heresy. Most enlightened people today don’t really think about heresy; it’s one of those archaic concepts from the past we barely comprehend. But to Christians of Isabella’s world, heresy was real; they believed it threatened the very salvation of their souls. Isabella certainly believed this and consequently she made a grave error in judgment, though she would not have seen it that way. She was motivated by her divinely appointed duty as queen to impose the only faith she deemed valid, rather than a heartless desire to terrorize her people.

Q: Tell us about a discovery you made that most surprised you about Isabella?

CWG: Well, I had no idea she was so forward-thinking in terms of women’s education. We have to remember that Isabella came to power in a Spain fragmented by many years of ineffectual monarchs; bitter antagonism and private feuds had sowed near-total disorder, and on top of this, the country itself was divided, with the kingdom of Aragón holding much of the north, Castile most of the rest, and the kingdom of Granada, the Moors’ last foothold, dominating part of the south. Once, Spain had been heralded for its erudition and advanced learning; by the time Isabella was born, even the wealthiest or most noble-born of men were barely literate, and women scarcely at all. She herself had no formal education, save for rudimentary basics. Comparing her educational schedule, as it were, with that of Elizabeth Tudor, born eighty-two years later, offers startling contrast. Here we have two of history’s most famous queens, each of whom became a symbolic personification of her land, yet while Elizabeth enjoyed an impressive upbringing that prepared her, even if accidentally, to be a monarch, Isabella had none. She lamented all her life her lack of education; in her early 30s, she dedicated herself to mastering Latin, and she championed a decree that facilitated women’s entry into universities. She was the first queen in Europe to mandate that women could earn degrees and become professors; she also imported and made available the first printing presses in Spain. Isabella was so intent on promoting women’s intellectual equality that she insisted her own four daughters be educated in the new Renaissance style; the infantas became such paragons of learning, they were highly praised and coveted as brides.

Q: How do you strike a balance between depicting the reality of the times with modern day sensibilities? Do you think issues Isabella faced in her era still resonate today?

CWG: It’s always challenging to depict the past in a way we can both understand and sympathize with. Issues of religion, race, sexuality, gender, as well as how animals were seen and treated, are fraught with controversy when filtered through the prism of the past, because people then barely recognized these issues at all, much less debated them. Many of the freedoms we take for granted were unknown to denizens of the 15th and 16th centuries, while deprivation, disease, prejudice, and inequality were part of their daily lives. Unfortunately, all of these problems remain part of our modern landscape. While we are in many ways a more enlightened society, we carry vestiges of the past with us, and leaders throughout the world grapple with some of the same issues that Isabella did, in terms of providing safety for their citizens, mitigating violence, and assisting the sick, the hungry and those whose lives have been torn apart by war and suffering.

That said, I must take into account the needs of my reader to be engaged by my story. While historical accuracy remains a primary obligation, I do sanitize certain aspects of the reality of life in the 15th century. We romanticize the past; we forget the lack of sanitation, dry-cleaning, antibiotics, etc. While I strive for authenticity and avoid a tendency to convert a brutal, quixotic era into “costume drama”, it is necessary to remember we can only take so much ‘reality’ in novelized form. In the end, I write fiction. My principal function is to entertain.

Q: What do you hope readers take away from your work?

CWG: I seek to reveal secret histories, and in some small way restore humanity to people whose legends have overshadowed them. I also hope readers will come away from my work with the experience that they’ve been on an emotional journey. I want them to feel the way these people lived, their hardships and joys, and differences and similarities with us. Though a Renaissance queen faced issues we don’t, love, hatred, power, intolerance, passion, and the quest for personal liberty are universal themes.

Q: What is your latest project?

CWG: I am currently working on my next historical novel about Lucrezia Borgia, tracing her so-called Vatican years, from her youth as the illegitimate child of an ambitious Spanish churchman to her sudden thrust into notoriety as the pope’s daughter and brutal, dangerous struggle to define herself as a woman even as she battles the lethal ambitions of her family. Lucrezia is my first non-queen, so to speak, though it could be argued that she was regarded as royalty in her era. Once again, I’ve found myself drawn into the opaque life of a woman who has been vilified by history as a poisoner and incestuous adulteress --- immoral and promiscuous, the sole female in the notorious Borgia clan. Who was she, really? How did she survive those dramatic, blood-drenched years when Pope Alexander Borgia held sway over Rome and dreamed of uniting Italy under his rule? What was her true relationship with her powerful father, whom it was said she adored and may have slept with, and with her brother Cesare, that enigmatic warrior who came to personify the very best and worst that the Borgias had to offer? I’m just beginning to explore Lucrezia and her world, and I’m completely enthralled by it, as I hope my readers will be.