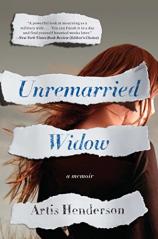

Author Talk: January 17, 2014

In UNREMARRIED WIDOW, 26-year-old Artis Henderson loses her husband 20 years after her own mother was widowed, and overcomes two generations of tragedy to discover that both hope and love endure. In this interview, Henderson discusses the painful process of retelling her story, her relationships with fellow army wives, and her plans for the future.

Question: How did you decide to write a memoir?

Artis Henderson: I believe we are given the stories we must tell. Even fiction writers are not so much making things up as mining their deepest selves, finding what it is they need to say. I tried briefly to write parts of this narrative as fiction, but it felt wrong. The only way to tell it, I realized, was to lay it bare, all of it, in its searing and difficult truths.

Q: This is a very personal memoir about a very difficult subject. What was it like to write? Did you find it helpful in processing what happened?

AH: The book was very demanding. Working on it, I felt as if I had stepped off the lip of a pond and sunk to the bottom. Life --- real life --- happened on the surface, but I was lost in the murk. I spent every day working at the library on painful scenes, and when I came home I would be emotionally wrecked. This went on for two years. But when it was done, I felt like an enormous weight had been lifted. I could finally say Miles's name without my voice cracking. As I was beginning the book, a friend had said to me, “The only way out is back through.” He was right.

Q: When you met the other young widows at the TAPS National Military Survivor Seminar, you talked about the terrible knowledge you all carry inside you and how you felt a responsibility to tell your stories. Do you see this book as being about more than your experiences? In what way is this, or is this not, a story about them as well?

AH: In my early conception of this book, I imagined it would be a collection of stories from war widows. I interviewed several women and tried to write their narratives, but I quickly realized that the only story I could tell --- really tell --- was my own. I often thought of the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, a single grave that stands for every soldier killed in combat. I hoped that in sharing my story I might illuminate the many stories that resulted from these wars.

Q: When Miles deployed, you chose to move home to Florida and separate yourself from military life as much as possible. You go on to say it never occurred to you that the other army wives on base might be a source of support and comfort. How do you think your experience might have been different if you had stayed?

AH: In the days after Miles's death, one of the wives in the unit mailed me a gift card to a restaurant. In her note she said that if I had been at Bragg she would have brought me food, but with the distance between us the gift card was the closest she could come. I was incredibly touched by her note, this was a woman I barely knew, and I realized in that moment that the other wives would have understood what I was feeling in a way people in the civilian world could not.

Q: In your Modern Love piece, you talked about how Miles’s death drew you closer to his mother, with whom you initially felt some tension. How has that relationship evolved since then? Do you still see his family?

AH: I'm still in contact with Miles's family, and I still care for them deeply. When I visit their ranch in Texas, I feel Miles there in a way I don't feel him anywhere else. He is very present on their land. I will always share a bond with the Hendersons and I am forever grateful to them for their kindness and generosity, both before Miles's death and after.

Q: You mention a widows’ support group that helped you as you grieved Miles. Do you still keep in touch with these women? In what ways have they been able to move forward? Are there ways they will never be able to move on?

AH: I still keep in touch with those women. I recently saw them after several years, and it was a festive reunion. We all wore this look of relief, as if we had survived the same storm. I picture the time we spent in the grief group together as a journey on a life boat, a journey we never thought we'd survive. One of the women said to me after the reunion, “I always said to myself that if I could make it to six years, then I would be OK.” We were six years out and shewas OK --- remarried to a good man, living in a place she loved. But even as she told me this she was crying and I cried, too, because after six years it still hurt.

Q: In the book, you wrestle with the question of how much our own desires matter and how much to give them up for love. Have you come any closer to answering the question? How have your personal experiences shaped your thoughts? Did the stories you worked on in your relationship column at Florida Weekly affect your thinking in any way?

AH: This is something I wrestle with every day, both in my mind and on the page. One thing I know for sure: sacrificing our own desires for someone else never works. Never. Peace comes from a delicate balance of personal goals and romantic compromises, but where that line lies I'm still not sure.

Q: In this story, you consult a psychic a few times, and on one occasion she tells you that you will see your name in print. How does it feel to hold a copy of your book in your hands? Do you think her words helped you go after your dream?

AH: Holding this book feels like magic. I cried at every step in the process, I was so overwhelmed by the wonder of it. The psychic confirmed that writing was possible for me in a way I had never before believed. If I was fearless enough, she seemed to say, if I was tenacious enough, then it would happen. And here it is, a long-held dream come true.

Q: The same psychic tells you that you will have a daughter and a son, and that you will remarry. And toward the end of the book, you hint that love might be on the horizon. Do you see this part of the psychic’s vision coming true any time soon?

AH: Yes, absolutely. In the first days after Miles died, I felt like I had this great surplus of love, a golden light that I carried around with me, that I had nowhere to direct now that he was gone. That light is still there, tucked away, but just as bright as it had been. I can't imagine going through the rest of my life without sharing it.

Q: At the end of the book, you moved to New York to attend journalism school. You’ve since graduated and written for all kinds of publications. Do you have any other projects in the works?

AH: When the writing of this book came to a close, I experienced a deep sadness. The book had been a way of keeping Miles present, and when it ended I felt as if I was letting go both of the story and him. But then I had lunch with a friend and he said to me, “Now it's time for you to find a new dream.” That's what I'm working on now --- my new dreams. I'd love to restore an old farmhouse in France, visit outlying Caribbean islands by sailboat, and hike the mountains of north Georgia. I'd also love to write another book.

Q: You’d always wanted to travel. Since this story occurred, you’ve spent time in France and Africa, and now live in New York City. How have these experiences enriched your life? Do you have any plans to travel more?

AH: When I'm figuring out the answer to a dilemma --- usually some version of What now? --- I try to take the long approach. I imagine myself as an old woman (always in a rocking chair, always on my porch) and I think about the stories I will tell of my life. My goal is to collect a rich assortment of adventures for that old woman, and for me the richest tales come while traveling. I have a trip to Ireland in the works, I'm always coming and going from France, and I've recently drummed up a new obsession --- travel by freighter boat. Talk about an adventure.