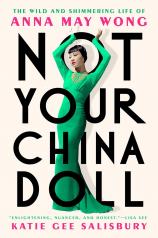

Not Your China Doll: The Wild and Shimmering Life of Anna May Wong

Review

Not Your China Doll: The Wild and Shimmering Life of Anna May Wong

I got lucky with Anna May Wong. Like most of the “boomer” generation, I’ve never knowingly seen her in a movie. But my mother, and her mother, probably did. Yet I know her name, thanks to having edited a fascinating academic textbook about Chinese diaspora filmmaking. Through this experience, I became acutely aware of the convoluted levels of racism around the world that prevented many talented Asian actors from ever reaching their deserved potential.

And in NOT YOUR CHINA DOLL, I learned that nowhere was cinematic racism against anyone Oriental-looking more rampant than in Hollywood. Although born in Los Angeles in 1905, right at the dawn of the film industry, Anna May Wong would be treated more as an outsider than an American, only to be recognized as a persevering stage pioneer after her death in 1961.

In writing the kind of book that she herself wanted to read --- in fact, it’s her very first book --- Katie Gee Salisbury has achieved a compelling and definitive biography that places Wong deeply within a society whose love-hate relationship with Oriental plotlines could be even crueler than overt discrimination.

"...a compelling and definitive biography that places Wong deeply within a society whose love-hate relationship with Oriental plotlines could be even crueler than overt discrimination."

In both silent and “golden age” talking pictures, white North American and European actors routinely played Chinese, Japanese and other Asian characters in “yellow face” makeup, with their eyelids stretched and glued at a slant. Sometimes Indigenous people were given bit parts because they looked more Oriental to begin with, which is just another form of racism. Yet, as NOT YOUR CHINA DOLL makes abundantly clear, there was genuine Chinese talent always at hand --- both homegrown and imported --- waiting in the wings and never auditioned.

From the time she started skipping school, or work at her father’s laundry, to hang around where studio crews were shooting urban scenes, Wong was determined to get into the film industry. And she managed to do so, despite subtle and overt social barriers, the US government’s draconian Chinese Exclusion laws, and dire warnings from family and friends that she would never make it.

As a teenager, Wong landed a variety of Asian character bit parts, mainly because she came to work naturally “made up.” But it was in a nondescript film made to demonstrate early color technology that she was noticed by none other than the legendary Douglas Fairbanks, who cast her as a sensuous dancing slave-girl in his epic Thief of Bagdad. For any other actor (read: Caucasian), that role would have launched a steadily ascending career.

In Wong’s case, it did indeed launch her into film, but only into Oriental villain roles that rigidly stereotyped her as a minor character who was usually killed off long before the ending. Again, institutionalized racism, this time in the form of a strict Hollywood morality code designed to protect white western “values,” relentlessly dogged her progress. Fellow actors adored Wong, and critics often noticed how much she made out of otherwise meager scenes, but everyone bowed to the rules of white cultural privilege. These details are especially important in NOT YOUR CHINA DOLL, as so few readers are likely to be aware of them today.

With the eruption of World War II and America’s late entry into the conflict following the bombing of Pearl Harbor, things became even worse --- not only for the American-born Wong, but for Asian actors everywhere. Nevertheless, as the powerful feminist saying goes, Wong persisted. She left to find more meaningful work in Europe and England, where she became an exotic rather than a marginalized figure and finally achieved some of the overdue respect and income befitting stardom, even minor stardom.

In effect, Wong’s professional life was a series of beginnings. Over and over again she relaunched her career, as attitudes to race and color slowly (too slowly) changed. And she did it largely on her own. Even though she had many relationships, she never married. Both laws and prejudice blocked even the road to love and motherhood.

But perhaps the biggest and most tragic miss of Wong’s entire career was being intentionally passed over for a role in the one film she really wanted, The Good Earth, based on Pearl S. Buck’s novel of the same name. The leading and most supporting roles went to white European and American actors. Personally and professionally, she had become what Salisbury describes as “the woman who died a thousand deaths.”

Although Anna May Wong tried to reinvent herself one more time during the dawn of commercial television in the mid-1950s, alcoholism and the relentless stress and effort of carving out a respected career had worn her out. In 1961, she died of a heart attack at the age of 56. Just the year before, she finally was given a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame and until 2019 was the only female Asian actor so honored.

A small consolation, perhaps, but her name will always be there. And Salisbury has sealed the deal magnificently with NOT YOUR CHINA DOLL.

Reviewed by Pauline Finch on May 3, 2024

Not Your China Doll: The Wild and Shimmering Life of Anna May Wong

- Publication Date: March 12, 2024

- Genres: Biography, Nonfiction

- Hardcover: 480 pages

- Publisher: Dutton

- ISBN-10: 0593183983

- ISBN-13: 9780593183984