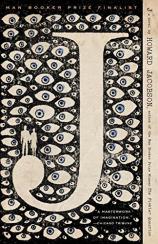

J: A Novel

Review

J: A Novel

In a 2013 speech entitled “When Will the Jews be Forgiven the Holocaust?” Man Booker Prize-winning British novelist and critic Howard Jacobson (THE FINKLER QUESTION) offered at least a partial explanation for why virulent hatred of the Jewish people continues to exist and, ominously, is growing in parts of Europe. “Those we harm, we blame,” he observed, “mobilizing dislike and even hatred in order to justify, after the event, the harm we did. From which it must follow that those we harm the most --- we blame the most.” Jacobson’s chilling question and its paradoxical answer lie at the heart of J, his new Man Booker Prize shortlisted novel --- part dystopian allegory, part love story --- that deploys the tools of fiction to illumine that troubling phenomenon without abandoning the novelist’s paramount obligation to tell an emotionally honest story.

Although the time and place in which it is set are never made explicit, J seems to take place a couple of generations hence in a country whose geography and culture don’t feel all that far removed from present-day Great Britain. The society has endured some form of mass extermination or exile that’s referred to only as WHAT HAPPENED, IF IT HAPPENED (Jacobson’s typography), reflecting a desire to bury all memory of the event. Equally ambiguous is the identity of the “aloof, cold-blooded” victims, whose “loyalty is solely to each other,” though the following description could hardly be more suggestive:

“Imaginatively, the story of their annihilation engrosses them; let them enjoy a period of peace and they conjure war, let them enjoy a period of regard and they conjure hate. They dream of their decimation as hungry men dream of banquets. What their heated brains cannot conceive, their inhuman behavior invites. ‘Kill us, kill us. Prove us right.”

"With no little amount of grace and considerable subtlety, [Jacobson] asks us to reflect, not only on the reasons for the persistence of anti-Semitism...but also to acknowledge the harsh truth that hatred of the Other seems an inescapable fact of human existence..."

Into this unsettling milieu, Jacobson introduces his protagonists: Ailinn Solomons, a beautiful 25-year-old who fashions paper flowers and her lover, Kevern “Coco” Cohen, a woodturner who specializes in producing lovespoons, and at age 40 already is experiencing “early-onset middle age.” They inhabit the small seaside village of Port Reuben, and like all citizens in a world where most people wear black and the predominant emotional color appears to be gray, they bear Jewish surnames. That’s the result of a program called Operation Ishmael, “that great beneficent name change to which the people ultimately gave their whole-hearted consent,” to ensure that “tracing lineage is not only as good as impossible, it is unnecessary.”

It gradually becomes clear that Ailinn and Kevern may have a larger destiny (one they sense dimly, at best) than the one inherent in their domestic relationship. Kevern’s movements are shadowed by a fellow teacher and artist named Edward Everett Phineas Zermansky and Detective Inspector Gutkind, who suspects Kevern of a double murder. Ailinn’s older friend, Esme Nussbaum, urges her back into the relationship with Kevern when it falters briefly early in the novel.

Unlike Orwell’s 1984, Jacobson only hints at the more authoritarian elements of his imagined world. People are “only prevented from leaving the country (or indeed from entering it) for their own good,” while reading groups are licensed, “allowed access to books not otherwise available (not banned, just not available).” In one of the novel’s most disturbing scenes, Kevern and Ailinn conclude a trip to the capital city (bitterly nicknamed “the Necropolis” by Kevern’s father), with a visit to a neighborhood their taxi driver describes as the one “where the Cohens lived.” When Kevern exclaims, “The Cohens! I’m a Cohen,” the driver replies, “No, I mean real Cohens,” and the erasure of what once was a vibrant community becomes frighteningly tangible. “They have the air of living lives on someone else’s grave,” Kevern says of the neighborhood’s inhabitants, his elegiac comment aptly summing up the novel’s predominant mood.

Despite that somber tone, J isn’t lacking occasional flashes of Jacobson’s well-known wit. Describing Kevern’s lovemaking technique, Ailinn says, “It’s as though you’re on a tourist visa. Just popping in to take a look around.” The novel’s concluding section opens with an excerpt from satirist Allan Sherman’s song “Shake Hands With Your Uncle Max,” which features a litany of Jewish surnames sung to the tune of an Irish ditty.

To the question he posed in his B’nai B’rith address, Jacobson proposed the haunting answer, “Never.” With no little amount of grace and considerable subtlety, he asks us to reflect, not only on the reasons for the persistence of anti-Semitism (and by extension other forms of ethnic animus), but also to acknowledge the harsh truth that hatred of the Other seems an inescapable fact of human existence, one that will persist until the day we’re no longer inhabiting this planet.

Reviewed by Harvey Freedenberg on October 24, 2014

J: A Novel

- Publication Date: September 1, 2015

- Genres: Fiction

- Paperback: 352 pages

- Publisher: Hogarth

- ISBN-10: 0553419560

- ISBN-13: 9780553419566