Excerpt

Excerpt

Hypocrite in a Pouffy White Dress

Chapter 1

Nudie Hippie Kiddie Star

WHEN I WAS LITTLE, I was so girlie and ambitious, I was practically

a drag queen. I wanted to be everything at once: a prima ballerina,

an actress, a model, a famous artist, a nurse, an Ice Capades

dancer, and Batgirl. I spent inordinate amounts of time waltzing

around our living room with a doily on my head, imagining in great

detail my promenade down the runway as the new Miss America, during

which time I would also happen to receive a Nobel Prize for

coloring.

The one thing I did not want to be was a hippie. "For Chrissake,

you're not a hippie," said my mother, fanning incense around our

living room with the sleeves of her dashiki. "You're four years

old. You run around in a tutu. You eat TV dinners and complain when

the food doesn't look exactly like it does on the packages. Hippies

don't do that," she said. "Hippies don't make a big production out

of eating their Tater Tots.

"Come to think of it, hippies don't torture their little brother by

trying to sell him the silverware, either," she added. "If I were

you, I'd worry less about being a hippie and more about being an

extortionist." But even by age four, I was aware of my family's

intrinsic grooviness, and it worried me no end. Like most little

kids-or anyone, for that matter-I suffered from contradictory

desires. While I wanted to be the biggest, brightest star in the

universe, I also wanted to be exactly like everybody else.

And so, I was enormously relieved when my parents announced we were

going away to Silver Lake for the summer. From what I understood of

the world, "going away" was what normal Americans did. It was 1969,

and my family was living in a subsidized housing project in Upper

Manhattan, in a neighborhood whose only claim to fame at the time

was that its crime and gang warfare had been sufficient enough to

inspire the hit Broadway musical West Side Story.

At Silver Lake, not only would we be taking a real summer vacation,

but, according to my mother, there was even the slight possibility

I'd get to be in a movie. Apparently, she knew a filmmaker there

named Alice Furnald, who had been casting around for kids.

To call Silver Lake a resort would be an exaggeration. It was a

summer colony founded by Socialists, people either too exhausted

from manual labor or too unfamiliar with it to care much about

landscaping. Small bungalows had simply been built on plots of

land, then left to recede back into the woods around them. Dirt

roads led to the eponymous lake, which shimmered, mirrorlike, at

the start of each summer before deteriorating into a green porridge

of algae by late August. The community's one concession to

civilization was "the Barn," an old red farm building used as a

recreation center. Otherwise, Mother Nature had been pretty much

left to "do her thing" as the colonists liked to say.

For a kid, Silver Lake presented infinite ways to inflict yourself

on this natural world, and my new friends quickly schooled me in a

range of distinctly un-girlie pleasures. Our parents might have

been sitting cross-legged on the grass nodding along to the

Youngbloods- "C'mon people now! Smile on your brother"-but

we had ants to incinerate and decapitate, worms to smush, frogs to

stalk, fireflies to take hostage, caterpillars to outwit, slugs to

poke at with a stick, berries to pulverize with a rock, and dead

moles to dig up in the garden and fling around the kitchen moments

before lunch. We discovered that if we scraped reddish soil from

the side of a mound by the lake, then mixed it with water, we got a

terrifically sloppy, maroon-colored mess. It stained our clothes

and the teenagers called it "bloody muddy," so of course we were

determined to play with it as much as possible. It was like the

caviar of mud.

Better yet was the four o'clock arrival of the ice cream man. I

suspect the London Blitz generated less hysteria and mayhem. As

soon as we heard the bells on the Good Humor truck jiggling up the

road, every single kid under the age of twelve went insane. "Ice

cream!" we shrieked. Dashing out of the water, we raced over to our

parents, snatched money out of their hands before they could finish

saying and get a Creamsicle for your father, please, then

zoomed up the hill barefoot and screaming. It wasn't so much the

ice cream man arriving as the ice cream messiah.

In Silver Lake, I romped through my days in a state of

semidelirium, fully at home in the world, happy in my skin.

Twirling and somersaulting in the sunlit lake, I was an Olympic

gold medalist, I was the queen of water ballet, I was a weightless,

shining goddess with nose plugs and a lime green Danskin bathing

suit that kept falling off my shoulders and riding up my butt. I

spent my days yelling, "Mom, Mom, Mom! Look at this! Look at this!"

then doggiepaddling around the kiddie pen like a maniac.

Yet like most idyllic things, Silver Lake seemed to exist in this

state only to serve as a backdrop for some pending and inevitable

craziness.

And that's where Alice Furnald and her movie camera came in. Alice

Furnald was known in the colony as an artiste with a

capital "A." While other mothers walked around in flip-flops and

rubbery bathing suits, Alice wore ruffled pencil skirts and

platform shoes and white peasant blouses knotted snuggly between

her breasts. Whenever she chewed gum-which was pretty much all of

the time- everything on her jiggled. I called her "The Chiquita

Banana Lady," and I meant this as a compliment: who didn't want to

look adorable with a pile of fruit on her head?

One night, Alice called a meeting at the Barn. "As you might know,"

she announced, "I'm planning to shoot a film here in Silver Lake."

Its title was going to be Camp, she said. If she meant

this ironically, she seemed unaware of it.

"Camp will star a number of people here in the colony,

including . . ." Alice stopped chewing her gum and looked pointedly

at me and my friend Edward Yitzkowitz. At that moment, I was busy

inventing a way to hang upside down from the bench while chewing on

a plastic necklace. Edward was shredding the rim of a Styrofoam cup

with his teeth. "Including," Alice cleared her throat, "some of our

very own children.

"Edward," Alice called across the barn. Like many of the colonists,

Alice had a thick Brooklyn accent. She pronounced Edward not

"Edward" but "Edwid." In fact, most of the colonists-including

Edward's own Brooklyn-born mother, Carly, and thus Edward himself-

pronounced Edward "Edwid." For years, I believed that was his real

name. Edwid. Edwid Yitzkowitz. (Only when we were grown

up, and I bumped into him in the East Village, did he inform me

that his real name was "Edward." Or had been Edward. Sick of the

wimpiness it implied, sick of its syllabic bastardization, he'd

gone ahead and changed his name legally to "Steve.")

"Edwid. Little Susie Gilman," Alice called across the barn. "How

would you two like to be in a real, live movie?"

Her voice had all the forced and suspicious cheerfulness of a

proctologist- it was the voice grown-ups used whenever they wanted

to coax children into doing something that they themselves would

never do in a million years unless ordered to by a judge-but I was

more than willing to overlook this. At that moment, I felt only the

white-hot spotlight of glory and attention shining down on me: it

felt like butterscotch, like whipped cream and sprinkles. I nodded

frantically. Of course I wanted to be in a movie!

The truth was, until Silver Lake, the year had not gone terribly

well for me. Sure, the Vietnam War was going on, and Bobby Kennedy

and Martin Luther King had recently been shot. But as far as I was

concerned, there was only one national trauma worth paying any

attention to: the birth of my baby brother. Not only did John's

arrival demolish my status as an only child, but he was handily the

cutest baby in all of recorded history. Decked out in his red

pom-pom hat and his pale blue blankee, he was the traffic-stopper

of the West 93rd Street Playground set. Other mothers abandoned

their carriages by the monkey bars. "Ohmygod, he is gorgeous! "

they'd squeal, pushing past me to poke their heads under the hood

of his stroller. "Does he model?"

I, on the other hand, was cute only in the way any four-year-old is

cute: big eyes, boo-boos on the knee, the requisite lisp. But my

face was round as an apple, my tummy even more so. I was not too

young, I quickly discovered, to have adults declare open season on

my weight. If anything, my brother's adorableness seemed to compel

them to point out my unattractiveness in comparison. It was as if

there was only a finite amount of cuteness in the world, and my

brother had used up our quota.

"Oh, your little girl, she so chubby!" bellowed the obese Ukrainian

woman who ran the Kay-Bee Discount department store, where my

mother bought my Health-tex clothing wholesale.

"I think she drink too much Hi-C," the teacher's aide at my nursery

school suggested. "Her face, it get fat."

My teacher, Celeste, was herself a genuine sadist. This was made

clear to me the very first day of nursery school, when she led our

class in a game of "Simon Says" designed to inflict flesh wounds:

"Simon says: Poke yourself in the eye! Simon says: Hit yourself

on the head with a Lincoln Log! Stick a crayon up your nose!

Whoops. I didn't say Simon Says, now did I, Juan?"

"Well, Susie certainly does like Cookie Time," Celeste informed my

mother with a naked, malicious glee. "And let's face it, she's not

doing herself any favors. Have you considered taking her to a

doctor?"

Halfway through the school year, I lay down in front of the door to

my classroom and shrieked until my mother promised to take me home.

So there I was: the Upper West Side's first bona fide nursery

school dropout.

But now, Edwid and I were going to be movie stars! "We're going to

be in a movie!" we sang on the ice cream line the next afternoon.

As any kid knows, it's not just that good things should happen to

you, but that they should be rubbed into the faces of everyone

else. "We're going to be in a movie!" we chorused again, wiggling

our butts in the universal hoochie-coochie dancetaunt, successfully

and immediately alienating every other kid in the colony.

In retrospect, Edwid was probably as hungry for some top billing as

I was. At four years old, he was already well on his way to

becoming a dead-ringer for Ethel Merman. Showy, gossipy,

melodramatic, he had a great froth of curly hair which he'd brush

back with a flourish, and a voice that trilled up the octaves.

"Ohmygawd, you guys, listen to this!" he'd exclaim. Never mind that

for some of his contemporaries, getting through Hop on Pop

was still a major accomplishment: Edwid had not just his mother's

Brooklyn accent, but her full-blown, intellectual's vocabulary.

"What child talks like that?" my mother remarked. "That kid is a

yenta."

And I adored him for this. All the girls did. Unlike other little

boys, whose primary hobbies seemed to be throwing rocks and plowing

into you while pretending to be Speed Racer, Edwid was opposed to

any kind of activity that required you to exert yourself. A

burgeoning chocoholic like myself, he was only too happy to sit in

a lawn chair eating Yodels and making up elaborate stories about

what would happen to everybody in the colony, if, say, aliens

landed in the Barn and enslaved people based on their

outfits.

Needless to say, the other little boys weren't quite sure what to

make of him. They were only four years old, and yet they knew-just

as Edwid himself surely must have known-that one of these

things is not like the others.

Slurping away on Fudgsicles, Edwid and I talked excitedly about how

our lives would be transformed by being stars in the movie.

The only child actress I knew of at the time was the ancient

Shirley Temple. Somehow, I had the idea that appearing in

Camp meant being the centerpiece of several vigorous

song-and-dance numbers: I envisioned myself solemnly descending a

staircase in a small white mink cape while a cast of adoring

grown-ups fawned around me, singing songs about how wonderful I was

until they left me alone in the spotlight for one of my many ballet

solos. I would then proceed to perform one perfect arabesque after

another, ending each one by flashing a peace sign at the camera

just like the Beatles did.

Edwid saw himself more as a magician. "I'm going to be in a long

purple cape and a silver top hat," he announced. "When I tap the

rim of my hat with a magic wand, pet rabbits are going to come

running out. Then," he added, "I'll lock my sister Cleo in a cello

case and make her disappear." It went without saying, of course,

that somehow Cleo would fail to rematerialize at the end of the

trick. Through no fault of Edwid's, she would remain lost forever

in a netherworld of incompetent magicians' assistants.

At the end of the movie, Edwid and I agreed, we'd both be in a

parade, then move to a split-level house inNew Jersey with shag

carpets and an aquarium and a kitchen stocked only with M&M's

and Bosco.

The morning that Camp was to begin filming, I woke up so

excited, I didn't want to eat breakfast. But there wasn't any

breakfast to be had-my mother was already down at the lake,

watching Alice shoot the first scene.

"Come take a look, sweetie," said my dad. "It's really something."

Until that moment, it hadn't occurred to me that there might

actually be other people in the movie besides Edwid and me.

Following my father down to the lake, I didn't know what to expect:

perhaps Alice would be seated in a director's chair while a few

colonists milled around in sparkly costumes, awaiting my arrival.

Maybe there'd be people practicing tap-dancing, or a collie with a

red ribbon around its neck, being groomed to appear as my

sidekick.

What I did not expect to see was twenty-seven hippies cramming

themselves into a pink and purple VW Bug.

They were, from my point of view, practically naked. The men had

only cutoff denim shorts, and the women who weren't actually

topless were wearing tiny, macram? bikinis crafted by Daisy Loupes,

a colonist whom even the others considered, in their words, "far

out." Daisy made her living selling handcrafted bathing suits at

music festivals. That people actually paid money for her creations

is a testimony to the strength of the hallucinogens of the time. At

Silver Lake, the older boys called Daisy's bathing suits "Bags o'

Boobs" and "Saggy Titty Sacks." They weren't being

uncharitable.

In place of everyone's clothes was psychedelic body art. Explosive

flowers and huge Day-Glo orange peace signs were painted on their

chests. Hearts framed their belly buttons, smiley faces grinned

from their shoulders and knees. Butterflies alighted from their

clavicles. One woman had yellow and orange rays of sunshine

radiating from her crotch; my friend Annie's brother, Jerome, whom

I already considered a freak because he was a white guy who

insisted on wearing his hair in an Afro, was entirely covered in

paint. Stripes of color swirled around him like a green and magenta

barber pole. The Fleming twins, a pair of teenaged girls who'd

baby-sat me once, had the words "Groovy" painted on one leg and

"Sock It To Me!" on the other, and "Make Love, Not War" emblazoned

across their tummies.

Each hippie had a number painted on their stomach, too, and as

Alice stood behind her tripod, she called out the numbers as if she

were operating a deli counter. I noticed that she was counting

backward, "Fifteen . . . Fourteen. . . ." Whoever's number was

called had to stuff him- or herself into the VW.

My father led me over to Alice. "You see," he pointed at her

camera, "Alice is going to have of all these people jump out of

that tiny car just like clowns in a circus." He seemed to think I

would be entertained by this, though the truth was that

clowns-along with puppets, forest fire commercials, and badly drawn

coloring books- scared the shit out of me. Hippies, so far, weren't

faring much better.

"This scene is called 'Ode to Joy,'" added Alice, not looking up

from her viewfinder.

I had no idea what an "ode" was, but trying to stuff twenty-seven

grown-ups into a VW bug didn't look like joy to me at all. It

looked like wishful thinking.

I watched my friend Abigail's father, a compact man with giant

purple daisies painted on his nipples, crawl under the dashboard in

a fetal position, while the Fleming twins wedged in behind the

stick shift. "Number Six!" Alice shouted. That was Larry Levy, my

friend Lori's dad. He was six foot two and had hot pink and yellow

flowers painted up the trunks of his legs and a peace sign on each

cheek. Watching him bend down and try to contort himself into the

trunk of the VW was beyond painful; it was practically traumatic.

Yet my father was grinning. "Give it up, Levy!" he shouted. "You

can't do it!" Larry turned around, smiled broadly, and gave my

father the finger. Then he jumped down into the trunk and pulled

the hatch closed behind him with a flourish, and everyone hooted

and applauded. My dad put both fingers in his mouth and whistled.

It seemed to me like every dog across New York state heard him and

promptly commenced yowling.

"Okay!" shouted Alice, "start cuing the music." A portable plastic

record player had been set up under a tree with the help of half a

dozen extension cords, and I watched Alice's teenaged son,

Clifford, slide a copy of Jefferson Airplane's Surrealistic

Pillow out of its sleeve and place it on the turntable.

A queasiness started to come over me, similar to the one I'd felt

each morning before nursery school. I stood there with my father

and tried to pretend that all of this was okay-that this was how

any other kid from my nursery school would be spending their summer

vacation.

No one paid the least bit of attention to me. "Okay, people,"

shouted Alice. "It's 84 degrees out and I don't want anybody

suffocating to death. Once my camera starts rolling, haul your ass

out of that car as fast as possible!" Then she shouted, "Clifford!

Music!" and the reverberating, psychedelic, maraca-laced opening of

the Jefferson Airplane song "She Has Funny Cars" boomed across the

lake.

"Roll 'em!" Alice shouted. The original idea, apparently, had been

to have the car "drive" up into the clearing and then have all the

hippies emerge, but once everyone was crammed inside, steering the

car became physically impossible. "Just get out when I call your

number!" yelled Alice. "One!"

Slowly, the car door opened and Adele Birnbaum, who'd smushed

herself in just a minute earlier, emerged. A lightning bolt painted

on her stomach hadn't fully dried; it bled into the purple "1"

above her belly button, creating a Rorschachy mess, but Adele just

grinned and wiggled and danced right into the camera while the

crowd hooted and cheered. "Two!" Alice yelled, and Sidney Birnbaum

emerged, dancing the funky chicken with an American flag wrapped

around his waist.

It all went smoothly until Alice got to hippie Number Six. It seems

Larry Levy had pulled his back out leaping into the trunk of the

VW. Alice had to stop filming while my father and Sidney Birnbaum

carefully extracted him from the back of the car and whisked him

off to the emergency room in Brewster. Nobody thought to remove

Larry's body paint beforehand, and I wondered what the nurses would

make of it. Oddly, it comforted me to think that Larry's kids might

be even more embarrassed by all this than I was.

By the time Alice got to filming her thirteenth flower child, most

of the real children had lost interest. They'd wandered over to a

grove of trees by the lake, where they invented a game in which one

person farted into a bag, then everyone else took turns sniffing

it. But I had no interest. I went off and sat on a rock by myself.

The vague upset I'd felt at the beginning of the shoot had

metastasized into a fullblown stomachache.

"Sweetie, it's just make-believe," my mother said gently. "I don't

like it," I said. "Why not?" she asked. "They're just having fun.

They're playing- like you do."

For some reason, hearing this only bothered me more. Grown-ups

weren't supposed to play. They were supposed to be stodgy and

boring. More importantly, they were supposed to be stodgy and

boring while paying attention to you while you played. They weren't

supposed to be dancing the funky chicken while you went off and

farted into a bag. It started to dawn on me then why hippies really

frightened me: they were competition. Their face paint, their

bubbleblowing, their naive and garish clothing-they wanted kids'

stuff for themselves. They wanted to be silly and irresponsible,

twirling around in the grass. But then what did that leave for us

real kids to do? And if grown-ups were busy being flower children,

who'd be left to be the grown-ups?

I made a great show of turning my back to my mother, though I was

flooded with gratitude that she and my father had opted not to pop

out of the VW themselves. "I just don't like it," I said. "That's

all."

Kneeling beside me, my mother gently brushed a piece of hair from

my eyes. "Alice says she's going to film you and Edward dancing

together by the lake tomorrow."

This news had its desired effect. I was a sucker for vainglory.

"Really? I'll get to dance?" I said.

Suddenly, I imagined Edwid in a sequined top hat and tails-not

unlike his magician's costume-twirling me around in the sand and

lifting me gracefully in the air in a diaphanous gown. The hippies

might "do their thing," but Edwid and I would waltz along the

water's edge, looking preternaturally glamorous and beautiful. The

next morning, my mother woke me up in the dark. "Okay, movie star,

let's get going," she sighed. "Why Alice has to do this at sunrise

is beyond me."

While it clearly wasn't my mother's idea of a good time, I liked

being the first people awake in the colony. It felt to me like we'd

won some sort of contest.

I pulled on my tutu and skibbled out onto the patio as the first

blush of sun seeped over the hills. Outside, it was chilly-colder

than I'd imagined-but the sky was streaked with gold and shell

pink, and the air was sweet with morning fog. I'd never seen a

morning look so magical: no garbage trucks, no sirens, just wet

leaves and a few ambivalent sparrows. When my mother and I arrived

at the lake, Edwid's mom, Carly, was already there. Carly must have

been close to 250 pounds, yet her weight seemed a necessity given

the size and volume of her personality. With her booming opinions

and a laugh that could shake fruit off a tree, she was a one-woman

piece of agitprop theater, a force of nature in plus-sized

bell-bottoms and paisley caftans. She carried Edwid slung over her

shoulder like a small bag of laundry; he was still in his Snoopy

pajamas, wheezing, spittle-lipped, crusty-nosed, half-asleep.

Before I could ask about his magician's costume, a car pulled up,

and Alice climbed out, followed by Clifford, who unloaded what

seemed to be a great avalanche of equipment. Though it was

fivethirty in the morning, I was impressed to see that Alice was

already dressed in a lime green maxi-dress with a matching turban

and full makeup. Her jaw was going frantically.

"Okay, people," she said, snapping her gum, "let's set up down by

the beach as quickly as possible. We're racing the sun here. Saul?

Where's Saul?"

Suddenly, I saw Saul Shapiro rounding the bend in his pajamas. Saul

was my friend Wendy's father, and he was easily the largest man in

the colony-he even made Larry Levy (now Larry Levy of backbrace-

emergency-room fame) look somehow insubstantial. He was

barrel-chested, with enormous hands and feet and a corona of thick

white hair. His baritone made anything he said-whether it was "Get

that gerbil out of the laundry hamper" or "Iris dear, hand me a

pretzel"-sound like the song "Some Enchanted Evening." Occasionally

mistaken for Walter Cronkite, Saul had special license plates on

his car, because, my mother said, when he wasn't lying on the beach

in plaid bathing trunks, he was actually a prominent New York state

assemblyman-whatever that was. All I knew was that he was Goliath.

He terrified me.

Now, Goliath was wearing a peppermint-striped nightshirt and a

matching, tasseled cap. I thought he'd also been too sleepy to get

dressed, but Alice explained that Saul was going to be in the movie

with us. The scene, titled "Ode to Innocence," would consist of

this: Edwid and I would dance around the beach at dawn, chasing a

butterfly, while Saul stood amid us in his nightshirt and nightcap,

playing a flute.

Obviously, not quite what I'd imagined. But okay. Soon, however, we

had a butterfly problem. Butterflies, it turned out, could be real

divas on a movie set. Unlike the rest of the cast, they could not

be ordered to show up. They had to be coaxed; they had to be

courted. Barring that, they had to be caught. While Alice set up

her tripod, Clifford was dispatched to the marshes with a butterfly

net and an old gefilte fish jar. After ten minutes of watching him

swing away blindly, Edwid fell back asleep and Alice wondered aloud

if she could spray-paint a moth. But then, Clifford's luck changed.

He came upon not one, but two monarch butterflies-in flagrante, no

less-and easily nudged them into the gefilte fish jar. We were in

business.

Saul took his position at the end of the lake with a tiny plastic

flute that looked doubly preposterous in his oversized hands. Carly

plopped Edwid down on the sand, "Edwid, enough with the sleeping,"

she said loudly, pinching his cheeks until Edwid yelled, "Maaa! All

right already!" and stood up unassisted.

My mother knelt down and combed my hair and fluffed out the tulle

of my skirt. I felt regal and prim, very nearly perfect. Then she

and Carly retreated to the stone terrace overlooking the beach,

where Alice had set up her camera. "Everybody ready?" Alice called

from behind the viewfinder. Saul, Edwid, and I all nodded. Then she

straightened up, clearly displeased. "Um, could we lose the tutu

and the pj's?" she said. I looked at my mother.

"No tutu, Alice?" she said. "Ellie, Ellie, Ellie!" Alice cried.

"This is the 'Ode to Innocence,' not the 'Ode to Las Vegas' and

'Ode to Corporate America.' I want children-naked children-children

like cherubs, dancing around the Pied Piper at sunrise, chasing a

butterfly. This is not a place for sequins. This is not a place for

trademark cartoon puppies printed on a pair of synthetic pajamas.

This is about nature." Hearing this, Carly shouted over to Edwid.

"Hear that, Edwid? This is about nature. Take off your

pajamas!"

My mother looked at me, unsure of how to proceed. "Susie, Alice

would like you to dance without your tutu," she said carefully. "Do

you want to do that?" "What's a cherub?" asked Edwid.

"Who cares what a cherub is?" boomed Carly. "It's a pagan symbol

appropriated by Christians for their paintings of the afterlife."

"No it's not. It's a naked angel," said Clifford.

"I don't want to take off my pajamas," said Edwid. "It's cold out."

"Oh, Mr. Yitzkowitz, it's not that bad," Saul chuckled avuncularly.

"Easy for you to say," said Edwid. "You're wearing a nightshirt and

a stupid hat."

"Edwid!" shouted Carly. "Don't talk fresh to Saul. He's a

Socialist." She turned to Alice. "I don't know why he's being

difficult. Once, when he was two, he took off all his clothing in

the middle of Gimbel's department store."

"They're also called 'seraphim,'" said Clifford to no one in

particular. "Do I get to be an angel?" I asked my mother. I had to

admit, this sounded pretty good to me, though I wasn't crazy about

the "naked" part. Every day, I changed in and out of my bathing

suit on the beach-all the little kids did in full view of

everyone-but I wasn't a toddler, like my brother, who ran around

naked all day long, and good luck getting him into a diaper and a

onesy for a trip to the Dairy Queen. Being naked in a movie did

seem slightly embarrassing, but maybe not if I was a cherub . .

.

"The sun's rising, folks," said Alice. "Are we here to create art,

or are we here to discuss the epistemology of cherubs and

complain?" "Edwid, stop being such a prima donna and take off your

clothes," said Carly. "Well, Suze?" said my mother.

Edwid shrugged, so I did the same. Frankly, I didn't know what else

to do. The general consensus was that shrugs meant "yes," so

quickly, our mothers helped us out of our clothes. The truth was,

Edwid and I mooned each other regularly-our friend Freddy Connors

had invented a game called "Butt In Your Face," which was a big hit

on the ice cream line-but standing naked when it was officially

sanctioned somehow made us very shy. We avoided eye contact with

each other.

"Oh, that's beautiful!" said Alice, ducking back behind her camera.

As soon as she said, "Roll 'em!" I decided I changed my mind. I

wanted my clothes back on. Now. But Saul was playing "Greensleeves"

on the flute and strolling toward us, and Alice was saying, "That's

it. Great. Now, Susie and Edwid, dance around Saul." And since it

was freezing, and dancing was preferable to just standing there,

Edwid and I just threw ourselves into it, breaking out our best

dance moves from our own, personal repertoire.

"Stop! Cut!" Alice yelled. "Ellen," she called to my mother,

"what's Susie doing down there on one leg? What's wrong with her

hand?" "Oh," said my mother. "She's performing an arabesque and

flashing a peace sign. It's a little ballet thing she likes to do."

"Oh for fuck's sake," said Alice. "Little Susie Gilman!" she

shouted down from the terrace. "Enough with the arabesques and the

peace signs. And Edwid, what's with the shimmying?"

What Alice had forgotten is that Edwid and I hadn't been raised on

Julie Andrews musicals. We'd had our diapers changed to Otis

Redding. We'd learned to walk listening to Donovan's "Sunshine

Superman" and Tina Turner's "River Deep-Mountain High." In the

bathtub, we regularly sang along to the entire soundtrack of Yellow

Submarine. When ordered to dance, Edwid had launched into his

version of the pony mixed with go-go moves he'd seen on the Sunday

morning kiddie show Wonderama. This, apparently, was not what Alice

had had in mind.

"Forget the dancing, you two," she ordered. "Just skip. Skip

joyously around Saul."

"Like this!" Carly shouted. She lifted up the hem of her caftan and

mimed skipping joyously across the terrace. Even Alice looked a bit

stunned at the sight. She turned back to the camera. "Skip," she

said.

Saul resumed playing his flute and Edwid and I skipped around him

furiously, in great, spastic movements with big, imbecilic smiles

plastered on our faces that we hoped approximated joyousness. We

twirled and flailed, pretending to conduct an enormous, invisible

orchestra with our entire bodies. We leaped. We pranced. We

waltzed. We sashayed. Neither of us had any idea what the fuck we

were doing. "Beautiful, beautiful!" said Alice. "You're children!

You're innocent! You're natural! Keep skipping!" She cued Clifford

to release the butterflies. One of them had clearly been

asphyxiated in the gefilte fish jar-it wafted down pitifully like a

dry leaf-but the other fluttered about wanly, and we chased it with

exaggerated dedication, our gusto fueled, mostly, by the fact that

we were freezing.

"Skip! Chase the butterfly!" Alice chanted. We skipped and chased,

skipped and chased, and then suddenly, Alice yelled, "Cut! It's a

wrap!" and Saul pulled off his nightcap and wiped his forehead with

it, and my mother came down and pulled me quickly into my tutu, and

Edwid was buttoned back into his pajamas and flung over Carly's

shoulder. Clifford was collapsing all of Alice's equipment and

carrying it back up the hill to the car, and Alice was muttering

"Where the hell did I put my thermos? I need coffee now," and then

she was off, and I heard her car sputtering as it started, the

tires crunching over gravel, and Saul was waving goodbye to us, and

the gate was swinging closed with a tlink! behind him and then,

that was it. It was all over.

One butterfly had vanished, the other lay dead on the sand,

sacrificed to art, to the "Ode to Innocence." The sun glinted over

the horizon. The lake was glassy and eerily still, as if we had

never existed, as if it had been preserved in time long before

humans started prancing about with their Super-8 cameras. My mother

and I stood alone on the beach.

"Well," she sighed, "I guess that's one for the history books.

Shall we get you back into bed?"

That afternoon, Edwid and I didn't say anything to the other kids

on the ice cream line about our less-than-stellar movie debut, and

they didn't mention it either, which was all just as well. The new

point of interest was Terry, the substitute ice cream man filling

in for Jack, the octogenarian regular, who was away on vacation in

the Adirondacks. Terry was a college kid. To make a tedious job

interesting, he'd made up scatological and sexual nicknames for all

of the frozen novelties, which he shared with us in a

conspiratorial whisper. If we asked him for a "Chip Candy Crunch,"

Terry would wink, "Oh, you mean a Chip Candy Crotch?" sending us

into convulsions. Nobody cared about some movie called Camp when

you could listen to Terry saying, "Here you go. Two Dixie Cunts and

a Poopsicle."

In fact, Edwid and I never spoke about Camp, period, even when it

was aired for the entire colony at the Barn, three weeks later, as

part of the annual "End of Summer" banquet held the Saturday night

before Labor Day. We sat on the wooden picnic benches beside our

parents, quietly clutching our Styrofoam cups full of Very Berry

Hi-C, watching the shaky camera work of the opening shot, in which

a disembodied hand spray-painted the word "Camp" on a woman's bare

midriff to the trippy sound of the Byrds' song, "Turn! Turn!

Turn!"

We watched the jiggly, lint-ridden frames panning over the lake to

the pink and purple VW bug. Applause and hoots sounded from both

the audience on film and the audience in the Barn, which was

essentially one and the same, as each hippie-clown emerged again

from the tiny car (the biggest cheers erupted when Larry Levy

emerged, strung awkwardly between the shoulders of my father and

Sidney Birnbaum). Then came scenes I hadn't seen before: My mother

and a guy named Morris, dressed in evening clothes, having a fancy

candlelit dinner on a wooden raft in the middle of the lake, while

being waited upon by a swimmer . . . the Fleming twins singing

Dylan's anti-Vietnam song, "Masters of War" accompanied by Clifford

on his vibraphone in a rowboat . . . some "avant-garde" scene in

which finger puppets alternated between reading aloud sections of

the Warren Report and poetry by Kahlil Gibran . . . halfway through

this mess came Edwid and me, dancing frantically on the beach

around Saul, who was occasionally decapitated by the camera angles.

I was sure everyone would burst out laughing at the sight of us,

but instead of snickers, there was an almost universal "Aaaaawwwww"

throughout the Barn as assorted mothers gushed: "Oh, that's little

Susie and Edwid! Aren't they cute!"

Before I could drink in this wave of admiration, however, the

camera cut away again to a playground in Brewster, filled not with

children, but with more hippies from the colony. The heading "Ode

to Innocence" filled the screen for a moment, graffitied on a piece

of fluorescent poster board, and then the camera zoomed back to the

playground, where it showed a montage of grown-ups running into a

sprinkler one by one, then piling onto a carousel loaded down with

an assortment of pinwheels, umbrellas, flowers, balloons, and peace

signs. Clearly, this was more the spirit of innocence that Alice

had been looking to capture: the rest of Camp followed the hippies

playing on seesaws and pushing each other on the swings for what

seemed like a good fifteen minutes.

The final shot, however, did feature two children again-Daisy

Loupes's twins, Sasha and Eli, aged three, walking naked,

hand-inhand, down one of the colony's dirt roads. On Sasha's tush

was painted the word "THE" and on Eli's the word "END." Upon seeing

this, the entire Barn went nuts-clearly, the colonists found this

supremely cuter than anything else-and I was suddenly indignant

that such a plum role hadn't been awarded to me instead. Why hadn't

I been filmed with the movie's closing credits painted across my

ass?

For one frantic moment, I tried to edit the scenes in my head,

refilming myself so that my dancing was more memorable, so that I

didn't look nearly as silly as I had, so that I'd switched places

with Sasha. I even considered telling people that it was really me

and Edwid, not the Loupeses, in the final scene.

But the lights came on, and as the adults all went about

congratulating each other on their performances, some kids in the

balcony began chanting "Nudie Boy! Nudie Girl!" and throwing

balled-up paper cups over the railing. Whether they meant to hit me

and Edwid or Sasha and Eli really didn't matter. Because only then

did I remember where I was: I was in a barn full of Socialists. A

freak among freaks.

For years after the dubious premier of Camp, I practically got a

migraine just thinking about it. It was an independent film that I

could only hope would remain forever independent of such things as

an audience and a projector. Ironically, I later became incensed

not by the fact that my parents had been hippies, but that they had

not been hippies enough: "You put me in some nudie Granola-head

home movie, but didn't take me to Woodstock?" I once shouted at my

mother. "It was 1969. Silver Lake was only an hour away from

Yasgur's farm. What were you thinking?" It seemed galling to me

that if I was going to have to be preserved for all time dancing

naked on a beach while a state assemblyman played "Greensleeves" on

a flute, at least I could've also gotten to say, Well guess what,

man? I saw Pete Townsend bash his foot through an amplifier.

Sometimes, I wondered why I cooperated. Okay, I was four- generally

not an age noted for its impulse control or savvy business sense.

But I could have lain down on the sand and shrieked my head off

like I did at my nursery school. Little kids think nothing of

throwing a fit at the foot of an escalator, or ruining an entire

day at the zoo over a forbidden hot dog, or whining loudly, "I'm

bored. Can we go home?" during a funeral. They're experts at

defiance. Why hadn't I exercised this age-given gift?

For a time, I even wondered if Alice cast me and Edward in Camp

because I was a pudgy girlie-girl and, for all intents and

purposes, so was Edwid. Could she have sensed that we wouldn't be

the type of kids to object-we were already at a disadvantage-that

we'd be hungrier, more vulnerable, more eager to please?

Only years later, I'd meet a girl named Dyanne, whose Tennessee

mother insisted on dressing her and her two sisters up in identical

sailor suits and pulling them through the town in a wagon decorated

to look like a boat for the annual Fourth of July parade, during

which time they were all bidden to sing interminable and

quasi-patriotic "boat songs" like "Sailing, Sailing, Over the

Bounding Main" and "Row, Row, Row, Your Boat" even though they'd

grown up landlocked. I would date a Robert Redford look-alike when

I was sixteen, whose mother used to dress up as "Mrs. Pumpkin" for

Halloween and insist that he be photographed with her in a

vegetable patch for her Christmas newsletter. How humiliating!

There would be other boys whose mothers would be only too happy to

pull out family albums to show me snapshots of their little

darlings caught for eternity picking their noses and peeing in the

dog's dish-one, even, dressed up like a girl by his older sister

and installed at a tea party. I would meet girls who were forced as

children to sing "Sheep May Safely Graze" in church while actually

dressed up as sheep. Who were carted out to dance the tarantella

for relatives. Who were encouraged to recite abominable rhyming

poems written by their mother entitled, "Reflections on a

Menopausal Picnic." Girls who were paraded about in ludicrous

Easter bonnets, who were photographed sitting on the toilet wearing

only Mickey Mouse sunglasses and a feather boa, who were ordered to

play the ukulele for neighbors, who were preserved in both film and

memory in the shipwreck of school talent shows. I would come to

realize that for everyone, childhood means having limited power, at

best, in the face of adults' pathetic and misguided ideas about how

children should behave. It means being hamstrung between the desire

to please and desire, period. Welcome to the world.

But back in New York, in the days immediately following our return

from Silver Lake, I thought about none of this. Thanks to my own

gnatlike attention span, I quickly became consumed by such new,

all-important projects as rearranging my crayons, lobbying for a

mink coat, and figuring out how to clip rhinestone earrings to my

hair without ripping it out of my head. Forgetting the shame of my

movie debut, I took away from it only one lasting impression: if I

was truly going to be a star, it would simply not be enough to

perform. Oh, no. I would have to direct as well. Thanks to Alice

Furnald, I added that to my list.

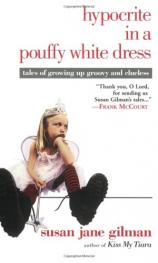

Excerpted from HYPOCRITE IN A POUFFY WHITE DRESS ©

Copyright 2005 by Susan Jane Gilman. Reprinted with permission by

Warner Books, an imprint of Time Warner Bookmark. All rights

reserved.

Hypocrite in a Pouffy White Dress

- Genres: Nonfiction

- paperback: 368 pages

- Publisher: Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-10: 0446679496

- ISBN-13: 9780446679497