Interview: September 14, 2023

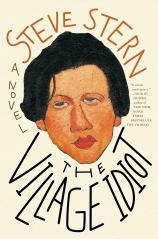

Award-winning author Steve Stern’s latest novel, THE VILLAGE IDIOT, is now available in paperback. This Publishers Weekly Best Book of 2022 is an imaginative portrait of expressionist painter Chaim Soutine's life --- from his impoverished beginnings in an East European shtetl, to his Cinderella patronage by the American collector Albert Barnes, and his perilous flight from the Nazi occupation of France. In this interview conducted by Michael Barson, Senior Publicity Executive at Melville House, Stern talks about how his approach to writing this book differed from that of his previous work; what drew him to write about Soutine in the form of a fictional biography; and who he would like to see involved in a potential film adaptation of THE VILLAGE IDIOT.

Question: THE VILLIAGE IDIOT is your sixth novel, though you also have had numerous collections of short stories and novellas published. What was the biggest difference in your writing approach here compared to the process you used for your first novel?

Steve Stern: In most of what I’ve written over the past 35 years, I’ve relied on my imagination, with characters conceived from whole cloth. Of course I’ve borrowed elements from history, folklore, autobiography, etc. But the stories have been of my own invention. With the artist Chaim Soutine, the protagonist of THE VILLIAGE IDIOT, I chose for the first time as my subject an actual historical figure, whose life provided a ready-made arc of narrative. This was a gift but also a constraint. Before, I’d always followed my characters wherever fancy led me, but with Chaim I felt obliged to be largely faithful to his real world history.

Thankfully (for my purposes), Soutine’s life has been poorly documented --- he was very good at covering his tracks. So there were ample opportunities to play a bit fast and loose with the “facts” of his life. In my fiction, I have always embraced an impulse to subvert to some extent the boundaries of common reality; it’s my way of trying to raise ordinary experience into the realm of the extraordinary, into myth. By immersing the known events of Chaim Soutine’s life in a somewhat fabulous dimension, I felt I could better extract the truth from the facts. It’s a method I think is not incompatible with the one Chaim himself employed in his paintings.

Q: You chose to write about your protagonist in the form of a fictional biography. How did Chaim Soutine come to your attention in the first place?

SS: I first encountered the paintings of Chaim Soutine at the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia. I had not known his work before. I saw landscapes suffused with a furious energy, saturated in riots of color, that made the houses, trees and human figures appear to be caught up in a whirlwind. It was as if the artist had experienced vertigo from the spinning of the earth. The still-lifes were often depictions of slaughtered animals whose radiance in death seemed to elegize their innocence and perhaps suggest a refusal to give up their souls. The portraits appeared to embody a kind of marriage of the beautiful and the grotesque: the faces and limbs fluid and distorted, their countenances pushed toward caricature, then beyond, so that each subject was endowed with a tragicomic aura. They elicited a range of often contradictory emotions that seemed to make of them the vessels of an intensely concentrated humanity. I’d never seen anything like them, nor have I since. They left me breathless.

Q: Was there any published biography of Soutine that you were able to draw on? What other kinds of research on him were you able to conduct?

SS: As I said, there was precious little documentation of Soutine’s life. No biographies in English, and only sketchy mentions of him in the biographies of other artists (Modigliani’s in particular). But some years after I’d viewed the paintings, I came across a book called SHOCKING PARIS by Stanley Meisler. It chronicled the history of a circle of artists known as the School of Paris, who lived and worked around the Montparnasse district of Paris during the early decades of the 20th century. They were mostly Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe, many of whom are now regarded among the foremost artists of the era: Chagall, Lipchitz, Zadkine, Moïse Kisling, Mane-Katz and others. Chaim Soutine figured prominently among them. The book described his upbringing in an impoverished Lithuanian shtetl, where he was raised in a culture that viewed drawing pictures as a brazen violation of the Second Commandment’s injunction against image-making.

It was in this context that Chaim, in the absence of any available models of art, conceived a passion for painting. For his efforts he was often severely punished, becoming cursed as a village pariah. I was intrigued by the mystery of an impulse that drove him to his drawings despite such disparagement, and the persistence of that lifelong obsession. I was fascinated by the notion that such a character --- unlearned, unwashed, misanthropic, practically barbaric --- made his way to a Paris that was at that time the center of the cultural universe. He was a misfit after my own heart, and I felt compelled to tell his story.

Q: In the course of writing this novel, did you reach any point that had you stymied at first? If so, how did you eventually resolve it?

SS: Honestly, this book was a lark to write. For one thing, I already had the template. I knew the various significant stations of Chaim Soutine’s life and had only the exhilarating task of organizing them (more in terms of their dramatic and aesthetic resonance than their chronology) and imagining the connections between them. It was a heady process, like playing variations on what I perceived as the theme of the artist’s existence.

I also had a kind of vision. I imagined Chaim in a diving suit trudging along the bottom of the Seine, hauling a bathtub on the surface of the river that contained his friend and mentor, Amedeo Modigliani. The scene takes place during a boat race for which the major artists of the day have built makeshift crafts to sail in a regatta as a grand diversion from the hardships of the First World War. Modigliani’s vessel is a bathtub, and his secret engine is his young friend Soutine, whom he’s persuaded to pull the tub from underwater.

A crazy concept, I know, but to my mind the perfect frame for containing the events of Chaim’s past, present and future in what amounted to a timeless element. And frame permitted the narrative, which begins with the boat race, to end with the boat race. In that way, after experiencing his entire life and ultimate death beneath the river, Chaim is snatched out of the water, released from the diving suit, and allowed (in a kind of rebirth) to proceed with his incomparable journey.

Q: Several famous movies have been made dramatizing the lives of great artists --- Minnelli’s Lust for Life about Van Gogh (1956), Altman’s Vincent & Theo (1990), Basquiat by Julian Schnabel (1996). Do you ever ponder what THE VILLAGE IDIOT might look like as a film? Who would direct it? Who could play Soutine? And would you want to be involved with the screenplay?

SS: The short answer is a resounding No! I never imagine that my stories will be adapted into films. I’ve had too many near-misses with writers and directors over the years, too many promised projects that never came to fruition. Enough disappointment already. The film agent who works with my literary agent expressed wild enthusiasm after reading THE VILLAGE IDIOT; she even phoned me to discuss possible directors and so on --- an unprecedented event. I thanked her kindly for her starry-eyed optimism and put the whole thing instantly out of my mind.

Of course, if we’re talking hypotheticals, and since Chico Marx and Leo McCarey are long dead, I’d tap Sacha Baron Cohen (with prosthetic lips) to play Soutine and the fabulist filmmaker Guillermo del Toro to direct him. And how about Johnny Depp as Modigliani…or Benedict Cumberbatch if Johnny isn’t available?

My one foray into screenwriting was as absurdly frustrating and disappointing as every other brush I’ve had with cinema, but that’s a story for another time. Suffice it that I know better than to ever revisit the experience.

Q: You have written several volumes worth of short stories, as well as some novellas. What is one key difference in your approach when writing a story versus a novel?

SS: I wish I had a ready answer. I love folk tales, fairy tales, the type of stories that are pared down to the very essence of narrative. The kind of story that harks back to the origins of storytelling, with roots in the oral tradition --- back when a story was meant to be an enchantment: think of Scheherazade beguiling the king in order to stave off her death. Such stories have an economy of means that renders them indelible, almost all heart, and so nearly impossible to replicate. But you can at least aspire to the like.

So in my fiction, I try to hold the narrative as close as possible to the model of a classic tale. And since tales generally imply a short form, I suppose I approach every story I write, initially in any case, as a short story. This attitude is also perhaps a way of teasing myself into believing that the task will not be so arduous, that the process will not involve years. As a consequence, I’m often deceived: the subject overflows its container. A larger container is required to accommodate the subject’s history, its milieu, and all the attendant details and complexities that come with doing justice to the story at hand. The tapestry has broadened, the characters multiplied, and it’s no longer so easy to maintain that essential compression to which you’ve aspired. So, before you know it, you find yourself writing a novel.

But all that said, I still reserve the right to think of a novel as merely a short story writ large.