Interview: May 15, 2014

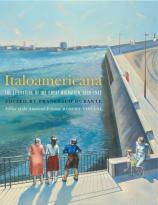

Francesco Durante is a journalist and Professor of Literature at the University of Suor Orsola Benincasa. Robert Viscusi, Ph.D., is Professor of English and executive officer of the Wolfe Institute for the Humanities at Brooklyn College, president of the Italian American Writers Association, novelist, critic and scholar. Between the two of them, they have quite a firm handle on Italian-American literature and culture. Durante curated and edited ITALOAMERICANA, a definitive collection of classic writings on, about and from the formative years of the Italian-American experience; Viscusi edited the American edition, which is now available. In this interview with Bookreporter.com, the two men discuss the limitations of Gay Talese’s 1993 essay “Where are the Italian-American Writers?”, why newspapers were vital to literary culture in the 19th and early 20th centuries, and how sometimes vital pieces of history can get lost.

Bookreporter.com: Is ITALOAMERICANA a work of cultural archaeology excavating a history we didn’t know existed? If so, would this be an explicit rebuke to Gay Talese’s 1993 essay, “Where are the Italian-American Writers?”

Francesco Durante: Yes, this is a work of cultural archaeology. I don’t know if we did not know that this history existed. We simply had forgotten it, not only in Italy. Also, Italian Americans had forgotten it because they could not read all this literature, which was published in the United States but was mostly written in Italian. It is the literature of the fathers, while their sons, becoming Americans, were not able to recognize themselves in a culture that was something different, in a culture that was not Italian anymore, but was not already American. A world apart. In this sense, this book could be a double rebuke to Talese’s essay: There were many Italian American writers when he wrote it, and there were many even before.

Robert Viscusi: Talese’s standards of admission to the company of American writers included big contracts, big reputations, big profits. Some of us (Fred Gardaphe and myself, to begin with) tried to convince him, while he was working on the famous essay, that John Fante, Pietro Di Donato, Mario Puzo and Helen Barolini belonged on his list, but he found reasons for not taking any of them seriously. They wrote, as he did not, from outside. They reflected the social subordination of the Italian Americans in the second generation. That might have gotten them a pass from Talese, had he not been in his prime as the Italian (almost the only Italian) voice at the New York Times. ITALOAMERICANA reflects the opinion of most Italian American writers that their history, at least until recently, had been conducted outside the walls of the literary establishment.

BRC: Mondadori originally published the book in Italy. Is the interest in Italian-American literature by Italian scholars relatively new?

FD: Yes. Starting in the 1990s, we had some very good works on Italian American literature. Prior to that, we had a lot of scholarly books --- especially in history, sociology, statistics, economics of the migration. But the idea that our emigrants could write books, well, nobody had it. Prezzolini and Cecchi, our outstanding critics, thought that the masterpieces built by emigrants in America were buildings, subways, railroads and the like, but not poetry or novels. From their point of view --- a very traditional and sophisticated one --- they were right. But they did not understand how much of real life was in those forgotten pages and how much of the mind of the so-called classi subalterne was there. America, in a certain manner, gave these people the chance to express directly their point of view, in their own voice.

RV: Italians have finally begun to be interested in the history and literature of Italian Americans. No surprise there. Italy, which for so long sent its emigrants into the world, has now become a destination for tens of thousands of poor people from other countries. These people come to Italy to work. They have children who frequent Italian schools. They grow up speaking the language perfectly and considering themselves Italians. These immigrant populations pose challenges and questions to people long accustomed to thinking of Italian as the name of a stable identity --- white, European and long-settled. The challenges of immigration from Albania, Libya, Somalia, Bangladesh, the Philippines and many other places south and east of Italy have awakened Italy’s interest in its own emigrant history. In 2004, Gian Antonio Stella published an important study entitled Gli Albanesi quando eravami noi (When the Albanians Were Us).

BRC: What were the different views between writers and Italy once they came to America?

FD: These writers were not professional writers. I mean, some of them were “intellectuals,” like the many journalists working in the myriad of Italian American dailies, weeklies, bi-weeklies and monthly papers. But the great majority of these publications were founded and edited by people who were doing humbler jobs. Nonetheless, they felt entitled to tell their stories: Think of what it could mean, at the end of the 19th century, going to New York or Chicago from a small village in the South of Italy. It was a real adventure, just like going from Earth to the moon…

RV: Once they arrived in America, some became model colonials, conducting parades on the Italian national day, collecting money for earthquake victims in Abruzzi. Some became children devoted to the parents they had left behind in Italy, sending money, medicines and other good things easier to come by in America than in Italy. Some became impassioned radicals and revolutionaries, enemies of the kings, dukes, cardinals and popes who laid down the law back home.

BRC: What about the cultural responses to the trauma of exile and immigration?

FD: These writings are also a response to that. Sometimes lyrical, sometimes political (in a very radical way).

RV: There is, for example, Vincenzo Vacirca’s narrative “The Fire” (1927), which recalls the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire of 1911 in tones of unappeased grief. The novels of Bernardino Ciambelli explore in great detail the many possibilities of fraud, delusion, deception and trauma that beset the lives of inexperienced Italians upon their first setting foot in the New World.

BRC: How difficult was it to find the documents you eventually included in the book?

FD: Gathering the materials was a hard task, but really incredibly satisfying. I had to visit about 70 libraries/archives on both sides of the Atlantic, and very often it happened that I found things I had not expected to find. Just an example: In the world, there is only one single copy of Il diario di un emigrato by Camillo Cianfarra. They have this copy at the Immigration History Research Center in Minneapolis. And I know only two copies of the novel I drammi dell’emigrazione by Bernardino Ciambelli: One is in the New York Public Library (or in Washington’s Library of Congress, I can’t remember in this moment), and the other copy is in the small Biblioteca Provinciale of the small Italian city of Avellino. Isn’t it fantastic?

RV: It was the drama of this hunt that first caught my imagination when I read Durante’s work in Italian. The accidents of history had caused these works to be forgotten and even hidden, just as the accidents of history had buried many of the great works of pagan antiquity after the fall of Rome. Humanist scholars like Francesco Petrarca and Poggio Bracciolini had gone in search of these works and, in so doing, started the revival of classical learning that was the bedrock of the Renaissance and of modern literary studies. Durante and a handful of other scholars, among them Martino Marazzi, have done some something similar for the Italians outside Italy, those who ventured into the wide world and wrote their histories and their observations. These are the true founders of Italian American literature.

BRC: During the time period this book covers, 1880-1943, Italian-language newspapers were very important, with hundreds being published across the country, especially in the major cities. Why?

FD: Newspapers were the cradle for this literature. Even if sometimes they sold very few copies, they were extremely important as a way to make the community stronger and give it a voice. And they were able to reproduce in America the extremely fragmented panorama of Italian political parties, especially the left wing parties --- so sectarian, so ideologically structured, always fighting upon very sophisticated matters.

RV: Indeed, newspapers were the literary engines of the 19th century. Great novels appeared as serials in newspapers. Newspapers created the metropolitan awareness that was the ground of nationalism. Newspapers in emigrant colonies sustained not only the language of the immigrants, but their awareness of what in meant to be Italian, to see oneself against the panorama of Italian history.

BRC: Theatre was also an important and popular art form for Italian-Americans during this time. Tell us a little more about that.

FD: Theatre is probably the area in which the first generation gave its best. And it is easy to understand why. Italians who came to America were in great part illiterate, but they had a very high capability to “perform”: not only music, songs and comical sketches, but also a lot of quite theatrical things, like religious festivals, and the tradition of Neapolitan or Sicilian humor, or that of the popular storytellers. If you think about this, you will find a powerful answer to the question: Why is American cinema so largely Italian? Because, basically, cinema is not the product of a “written” culture. It’s pop culture.

RV: It sometimes seems to me that, while they were building an Italian literature in America, the colonials also needed to build an Italy that they could use as material for reflection. All these developments --- the mass of theatricals, the flowering of political activity, the building and buying of houses, the founding of restaurants, the practicing of instrumental and vocal music --- were elements in an Italian scene that began to reach its full flowering in recent decades, in the fiction of writers like Mario Puzo, Helen Barolini, Anthony Giardina and Don DeLillo, and in the poetry of writers like Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Gregory Corso, Donna Masini and Lucia Perillo.

BRC: Will there be a sequel to ITALOAMERICANA?

FD: Actually, in 2002 I published in Italy a smaller anthology called Figli di due mondi (SONS OF TWO WORLDS), dealing with Italian American narrators of the '30s and '40s, mostly second generation, and all writers of English. Great narrators such as John Fante, Pietro Di Donato, George Panetta, Guido D’Agostino and many others that Talese could have mentioned in 1993 had he known something about them.

RV: And there will be more. Much more.