Excerpt

Excerpt

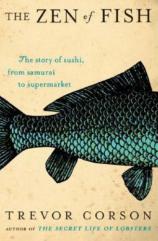

The Zen of Fish: The Story of Sushi, From Samurai to Supermarket

Chapter 9. “Hollywood Showdown”

On the morning of the Hollywood party at Paramount Pictures, Toshi

arrived at the restaurant well ahead of his staff. By 10:00 a.m. he

was hard at work in the kitchen. The party would begin in eight

hours.

Toshi stood at a stainless-steel table that would look at home in a

morgue. The table was 12 feet long and ran diagonally across the

kitchen. On its surface was a cutting board of high-density

polyethylene, chemically fused to repel bacteria, fat, and blood,

but soft enough that Toshi could wield his high-carbon blade for

several hours without dulling its razor-sharp edge.

Toshi bent over a big block of blood-red flesh. When sushi first

became popular in the early 1800s, a high-class chef like Toshi

would have been run out of town for serving tuna. The bloody meat

of fresh tuna and other red-fleshed fish spoils easily and the

Japanese considered it smelly. The fatty belly meat of the tuna was

especially despised. But with the advent of refrigeration, the fish

could be kept fresh, and in the years after World War II the

Japanese learned from Americans to love red meat, including

tuna.

Takumi, the Japanese student, stood across the table and watched.

On his cutting board sat a similar but smaller slab of tuna.

Toshi carved through the block of flesh like a sculptor,

scrutinizing the muscle, turning and trimming. He tossed scraps

into a bowl.

“We’ll use these for spicy tuna,” he said. He was

speaking Japanese, but the words “spicy tuna” were in

English. There isn’t even a name for it in Japanese. In the

early days of American sushi, Japanese chefs in L.A. had realized

they could take the worst parts of the fish—the fibrous

scraps, the flesh left on the skin, and meat past its

prime—and chop them up with chili sauce. The taste of the

fish was lost, but Americans loved it.

“The Mexican influence here is strong,” Toshi told

Takumi. “Americans like spicy food more than Japanese people

do.”

Takumi nodded. In a few minutes, he would scrape shreds of meat off

the skin with a spoon, chop them up with the other scraps, and

squirt the mixture full of hot sauce. But now he tried his hand at

trimming his slab of tuna. When he started to cut, Toshi stopped

him.

“No, not like that. You’re cutting in the same

direction as the fiber.” With his finger Toshi traced the

parallel lines of connective tissue that ran through the

tuna’s flesh like the grain in a piece of wood. “See?

You’ve got to cut against the fiber.” Toshi flipped the

slab of meat over, so Takumi could slice into it from the other

side. “Cut them thinner than you would for the

restaurant,” he added. “For a catering job like this,

we go for volume.”

Other restaurant staff trickled in to help prepare for the party.

Toshi’s office assistant dumped a two-pound bag of bright

green powder labeled “wasabi” into a mixing bowl. Like

most wasabi served in restaurants, there wasn’t a shred of

wasabi in it. Real wasabi is a rare plant that is notoriously

difficult to grow, and tastes quite different. This was a mix of

horseradish and mustard powder. She added water and stirred. The

powder jelled into a green blob, which emitted fumes. Toshi

wheezed.

“Get the hell out of the kitchen with that thing!” he

bellowed. “It’s going to drive us all

crazy.”

The woman bowed, hugged the bowl to her chest, and left, her eyes

watering.

Soon Kate and the other students trickled in and loaded the

catering equipment into a rented truck. Jay shouted out

instructions.

“Bring a minimal amount of stuff with you!” Jay said.

“Do not bring big bags! Otherwise, you’re not going to

get through security!”

But of course, they took their knives.

The students would ride in the restaurant’s old van. Kate

hopped into the front passenger seat and pulled the door shut with

a bang. They cruised down the freeway. In the distance the glass

towers of downtown L.A. rose through the haze. Soon they were

driving straight toward the gigantic white “HOLLYWOOD”

letters on the hill. They pulled alongside a vast, high-walled

compound. Security cameras monitored the van’s arrival.

At the security checkpoint there were men with guns—big guns.

Some rested Winchester rifles on their shoulders. Others carried

six-shooters on their hips. Most of them wore ten-gallon hats and

chaps. They were actors. The real guards wore windbreakers and

carried walkie-talkies. The actors passed their guns to the guards

and walked through the metal detector. When the guards saw

Kate’s chef’s jacket, they found her name on a list and

waved her through, along with her case of knives.

Inside the compound Kate followed her classmates past a row of

hangars and emerged onto the edge of an American frontier town of a

hundred years ago, bustling with inhabitants of the Old West. The

sushi students wandered into the town like a gang of lost samurai.

Around them cowboys twirled lassos. The smell of grilled beef

swirled through the streets.

The town continued for blocks. In the distance a pointy white water

tower perched on stilts. Painted on its side was a snowy mountain

under the word “Paramount.” Kate shambled through the

streets clutching her knife case. Ahead she saw Toshi and some of

the staff setting up their sushi stall on a street corner.

• • •

More than sixty restaurants would be hawking food from colorful

stalls—most of it seared or baked or fried, all of it

smelling delicious. Some of those restaurants were legends.

Pink’s and its “famous hot dogs” had started in

the 1930s. The stall beside the sushi stall was belching smoke. It

was called “The Pig.” When Toshi found a chance to slip

away for a few minutes, he’d make a beeline for Lawry’s

roast beef.

Now he buttoned up his chef’s jacket and surveyed the

equipment—the 25-gallon coolers filled with fish, the

insulated containers of rice, the cases of knives, the soy-sauce

bottles, the blocks of disposable chopsticks.

Then he surveyed the students. Some were helping set up, but others

stood around, not sure what to do. His eye lingered on Kate.

“We need backup,” he said to himself.

Toshi rooted in the pile of equipment for his secret

weapon—the Suzumo SSG-GTO. He located the black padded case

and carried it to the back of the stall.

The Suzumo SSG-GTO looked like a wooden tub with a lid. Sushi chefs

had been keeping rice in wooden tubs for nearly 200 years. This tub

was different. Toshi tugged an electrical cord out of the back and

searched for an outlet. He froze. This was the Old West. There were

no outlets.

Toshi scowled and scanned the street for a grip. He’d been

around Hollywood long enough to know that anywhere movies were made

there was electricity. You just needed a grip to show you where it

was. He spotted a man bristling with tools, gadgets, and brackets

hanging off belts. Toshi dragged the fellow over to the sushi

stall. The grip knelt and unscrewed a steel plate in the ground.

Inside was an array of heavy-duty sockets. Toshi powered up the

GTO.

Like the town around him, the wood on Toshi’s wooden tub was

fake. He lifted off the plastic lid and dumped in cooked rice. He

pressed a button. A drawer slid out. He typed instructions on a

keypad and the GTO hummed to life.

Toshi’s wife and children had arrived. His son Daisuke rushed

over to the GTO. The Japanese student, Takumi, joined them and the

three of them leaned over the machine, hands on their knees, and

peered inside.

Like the robots that build cars in the factories of Toyota and

Honda, sushi-making robots have become commonplace in Japan,

laboring tirelessly behind the scenes at mass-market sushi

establishments. In Europe, owners of conveyor-belt sushi

restaurants have been known to install elaborate, stainless-steel

sushi robots in plain view, where customers admire their high-tech

wizardry. But in the U.S., sushi robots are a well-kept secret.

Most restaurant owners keep them out of sight, and use them for

takeout and delivery orders.

Toshi pressed a button on the GTO. Gears clicked and motors

whirred. The GTO could crank out professional-grade rectangles of

pressed sushi rice at speeds approaching 1,800 per hour. But it

jammed. Toshi cursed.

“It’s not working!”

The Zen of Fish: The Story of Sushi, From Samurai to Supermarket

- hardcover: 384 pages

- Publisher: HarperCollins

- ISBN-10: 0060883502

- ISBN-13: 9780060883508