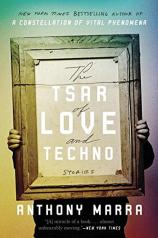

The Tsar of Love and Techno: Stories

Review

The Tsar of Love and Techno: Stories

In 2013, I had the pleasurable task of reviewing Anthony Marra's first novel, A CONSTELLATION OF VITAL PHENOMENA. Set in Chechnya during the wars that ravaged the country in the waning years of the 20th century, I described it as "gorgeous and gut-wrenching." From his new collection of linked stories, some of which share that setting, it's clear that Marra has far from exhausted his interest in that devastated land and its people. But in THE TSAR OF LOVE AND TECHNO, he's broadened his field of vision to take in Russia after the fall of Communism. It's a tour de force that only confirms the sound judgment of the National Book Critics Circle in awarding Marra's novel its inaugural John Leonard Prize for the best first work of the year.

"The Leopard," the story that opens the collection, introduces some of the book's central themes and, most notably, an object that appears in several other stories: a painting by the 19th-century Russian artist Pyotr Zakharov-Chechenets with the bland title of "Empty Pasture in Afternoon." The painting of an empty hillside near Grozny, Chechnya, is the object of the protagonist's work as a "correction artist," as he airbrushes disgraced figures from photographs and works of art during the Stalin era of the 1930s. In "A Prisoner of the Caucasus," Zakharov's pasture becomes the setting for the captivity of two Russian soldiers (one of them a recurring character) in 2000, and the scene of a devastating event in the life of the narrator of "The Grozny Tourist Bureau," while the actual painting is pursued avidly by characters in two other stories.

"It's a tour de force that only confirms the sound judgment of the National Book Critics Circle in awarding Marra's novel its inaugural John Leonard Prize for the best first work of the year."

If that description makes it sound at all like Marra's linking is nothing more than a clever literary parlor trick, that would be an erroneous conclusion. One could read this collection several times without sacrificing the pleasure of teasing out all the threads of connection he has so delicately stitched. They emerge gently and organically in these stories, giving the book a novelistic feel, as when the full force of the correction artist's work finally resonates in the life of another character in "A Temporary Exhibition" nearly seven decades later.

Russian or Chechen, Marra's characters struggle to come to terms with life in the post-Soviet era. "They longed for the old days, not because their lives had been better, but because there had been an equality of misery back then," he writes in describing this state of mind. An aging, impoverished woman similarly wonders "how do you trade your gods so late in life?" Like most of her fellow citizens, she faces a grim future, made more desperate by straitened economic prospects. Whatever their circumstances, and along with murderers, drug dealers and people who betray family members to the authorities, Marra portrays his characters with deep empathy, no matter the gravity of their damaging, often inexcusable, choices.

Marra demonstrates his narrative skill by choosing to place all or portions of several stories in the singularly unattractive Siberian town of Kirovsk. It's a former labor camp that's been transformed into a "poisoned post-apocalyptic hellscape," whose nickel smelters, dubbed the Twelve Apostles, ring a massively polluted body of water dubbed Lake Mercury and where stands of metal birch trees with plastic leaves, ironically called the White Forest, substitute for the vegetation that can't grow in the contaminated air.

Out of this dismal backdrop come two of the collection's more memorable characters: Kolya, a young man whose limited prospects transform him into a Russian conscript in Chechnya and a drug-dealing thug when he returns home, and Galina, Kolya's high school girlfriend, who parlays a win in the Miss Siberia Beauty Pageant into marriage to Russia's 14th richest man and movie stardom. Their divergent paths illustrate what seem to be the arbitrariness and extremes of life in modern Russia.

Whether one calls it black or bleak, Marra specializes in a kind of humor that's as revealing of character as it is downright funny. The ex-convict father in "A Temporary Exhibition" swells with pride at the computer prowess of his son, who employs that skill to prey on the finances of elderly Americans. In "The Grozny Tourist Bureau," Ruslan Dokurov, the former deputy director of the art museum, is recruited by the Chechen Interior Minister to boost tourism, now that the fighting has waned. He spends weeks designing a brochure, wrestling with the dilemma of how to "trick tourists coming to Grozny voluntarily." When asked by the translator for a group of Chinese oilmen he's chauffeuring around the city to identify a "small mountain range of rubble bulldozed just over the city limits," he replies, "Suburbs."

Marra concludes THE TSAR OF LOVE AND TECHNO with "The End," set in "Outer Space, Year Unknown." It's the lovely, if mysterious, vision of Kolya breaking free of the shackles that contain him and many of the other subjects of these stories. Like a contemporary Chekhov, one would be content if Marra continued to mine the subject matter that has engaged him so strikingly in these unforgettable tales. Whether he does, or moves on to other material, he'll assuredly remain one of our most distinctive and talented young writers.

Reviewed by Harvey Freedenberg on October 13, 2015

The Tsar of Love and Techno: Stories

- Publication Date: July 19, 2016

- Genres: Fiction, Short Stories

- Paperback: 384 pages

- Publisher: Hogarth

- ISBN-10: 0770436455

- ISBN-13: 9780770436452