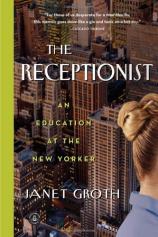

The Receptionist: An Education at The New Yorker

Review

The Receptionist: An Education at The New Yorker

With memoirs by accomplished writers like Brendan Gill, Lillian Ross and Renata Adler, and a host of shorter reminiscences by others associated with the publication, it’s not surprising that one might greet the arrival of yet another account of a stint at The New Yorker with a less than enthusiastic response. That skepticism is only likely to be magnified on learning that the memoir has been written by a woman whose 21-year tenure at the magazine consisted of serving as a receptionist. I can report happily and confidently that readers should set aside any feeling of reluctance to pick up THE RECEPTIONIST. That’s because Janet Groth has done a more than capable job, not merely of sharing some amusing stories of life at The New Yorker, but also of portraying the coming of age of a young woman from small town Iowa in New York City as it made the dramatic transition from the placid 1950s to the clamorous 1970s.

"Janet Groth has done a more than capable job, not merely of sharing some amusing stories of life at The New Yorker, but also of portraying the coming of age of a young woman from small town Iowa in New York City as it made the dramatic transition from the placid 1950s to the clamorous 1970s."

Groth was nothing if not the beneficiary of some remarkable good fortune. Fresh from the University of Minnesota in 1957 and on the strength of a single recommendation, she found herself in an awkward interview with E.B. White, trying to explain why her conscious decision not to develop her typing skills shouldn’t prevent him from hiring her. It didn’t, and she was assigned to the 18th-floor reception desk, where her job combined message taking, errand running and a host of other chores for a stable of some 40 writers and six cartoonists.

Apart from the diversity of her tasks, Groth was no ordinary receptionist. While occupying what she calls “the world’s least busy reception desk,” she pursued advanced degrees in British and American literature (Dwight Macdonald wrote a “scorching” letter on her behalf to his friend Jacques Barzun when he learned her application to Columbia’s graduate school was languishing), eventually securing a PhD from NYU. She’s written or collaborated on several books on Edmund Wilson and has taught at Vassar and Columbia. She even lost out to Sylvia Plath in the Mademoiselle magazine writing contest that helped launch Plath’s career.

Groth judiciously doles out the character portraits and revealing tidbits that are the grist of most contemporary accounts by those who come into contact with famous figures. She devotes chapters to her time as a student of John Berryman at Minnesota (including his semiserious marriage proposal), her visit to Muriel Spark in Italy and her six years of Friday “literary lunches” with Joseph Mitchell, one of the magazine’s most famed contributors of the era whose career ended with a disastrous attack of writer’s block lasting more than three decades. “Joe considered me something of an oddity,” Groth writes, “combining in one (he thought) shapely body a fondness for both bohemia and Buber.” Literary luminaries like J.D. Salinger, who periodically set off on futile searches for a nonexistent Coke machine; Woody Allen, who had a penchant for getting off the elevator on the wrong floor; and Dorothy Parker make cameo appearances.

Groth devotes a considerable portion of her story to her disastrous relationships with a succession of men. Her first serious one, with a cartoonist she met during a brief (and unsuccessful) detour to the art department, led to a suicide attempt. That was followed by a three-year affair with a German expatriate playwright and translator. When he abandoned her for another woman, she “began acting out the role of the party girl/woman of the world.” While the account of that interlude, one notable for its promiscuous sex, an unintended pregnancy and excessive drinking, will seem tame by the standards of modern memoirs of dysfunction, there’s no doubt Groth’s struggle and pain were profound. The period culminated in a lengthy trip to Greece in 1965, from which she returned “ready to undertake the effort of living with a new, more authentic self.”

By that time, a great new generation of writers like John Updike, Calvin Trillin and John McPhee (but not Tom Wolfe, with whom Groth had a brief encounter and who savaged the magazine in two famous New York Herald Tribune pieces) had arrived. As it tried to keep pace with the political ferment of that decade, Groth describes how the magazine took on a decidedly more political cast under the editorship of William Shawn, featuring Rachel Carson’s SILENT SPRING and Jonathan Schell’s reporting on the Vietnam War among other controversial pieces. More observer than participant, Groth found herself caught up in some of the political turmoil of the time when she shared a West Village apartment with a young African-American woman whose relationship with a man involved with the Nation of Islam brought her to the event where Malcolm X was assassinated in 1965.

In his memoir ABOUT THE NEW YORKER AND ME, E.J. Kahn, Jr. good-naturedly described Janet Groth as one of the magazine’s “authentic oddities.” But as she gracefully demonstrates with affecting modesty in this memoir, Groth was much more than that, and her two decades in a humble role were anything but wasted.

Reviewed by Harvey Freedenberg on July 20, 2012

The Receptionist: An Education at The New Yorker

- Publication Date: June 11, 2013

- Genres: Nonfiction

- Paperback: 240 pages

- Publisher: Algonquin Books

- ISBN-10: 1616203064

- ISBN-13: 9781616203061